Colin Jones, Paris: A History

Haussmannism and the City of Modernity

1851-89

The roles of Napoleon III and Haussmann

The return to power of a Bonaparte in 1848 instigated a reprise of the imperial themes and the grandiose scale of operations which Napoleon I had sketched out for the capital of his European empire. Even while he was still President of the Republic, Emperor Napoleon III (as Louis Bonaparte made himself in I 8 52) was planning the revitalization of the nation's capital. Legend had it that he had arrived at the Gare du Nord [one of the principal train stations in Paris] in 1848 with a rolled map under his arm containing the future new boulevards sketched out in coloured pencils. His seizure of executive power in 1851-2, which roused widespread opposition on the streets of Paris, increased the resources at his disposal and boosted his ambitions. The period up to the overthrow of the Second Empire in I870 and the establishment of the Third Republic (1870-I940) was to be characterized by a programme of urban renewal perhaps as ambitious and as far-reaching as any in western history. The result was a Paris which by the end of the century had new boundaries, a new configuration and, in some respects, a new identity, as the city of modernity.

The Second Empire innovated not by building alongside and outside the old centre, but rather by locating innovation at the very core of the city almost for the first time, in the heartlands of the radical sans-culotterie [groups of lower class radicals] which had opposed Louis Bonaparte's rise to power, and indeed had demonstrated against his 1852 coup d'etat. Perhaps the most striking feature of the transformation was a new and more highly integrated system of straight and broad roadways which tore through the antique fabric of what was already coming to be called le Vieux Paris ('Old Paris'). Others included the prioritization of circulation the harmonization between monuments and means of communication, the provision of green space and the articulation of an infrastructure which could cope with a larger and more densely occupied site. . . .

The personal influence of Napoleon III on his proclaimed mission of renovation should not be underestimated. Nevertheless, it is difficult to disentangle his activities from the role also played by Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann, whom in r853 Napoleon III designated the Prefect of the Seine, and who remained in power until only a few months before Napoleon's own overthrow. The loss of vital documents, notably in the extensive incendiarism of 1871 following the ignominious end of the Second Empire, makes exact adjudication of their respective parts impossible -- as do Napoleon III's tendency to vainglorious self-promotion, and Haussmann's rhetorical propensity for stressing his own role as mere 'instrument' and 'servant' of his 'master'. If contemporaries tended to ascribe more credit to Haussmann, this was partly because they found it difficult to imagine that a man like Napoleon could possibly have a profound influence on a city he appeared to know so little. Before 1848 he had never lived in Paris save as a baby and as a fleeting tourist, and as emperor he would on occasion get lost making the simplest of journeys. Haussmann, the 'Alsatian Attila', in contrast, had spent a happy childhood in the capital before his family had moved to eastern France. It was the name of Haussmann which, moreover, was to endure. The Bonaparte name was execrated throughout the Third Republic, so that it was not 'Napoleonism' but 'Haussmannism' that was recognized as an influence -- a continuing influence-on the remodeling of the capital.

Napoleon III and Haussmann

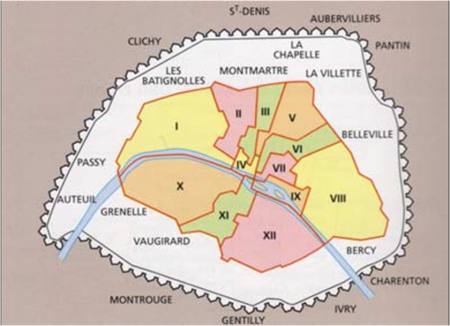

Paris Before 1863

Colored areas are subject to special tax on all goods brought in