The Career of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904)Since you will be trying to understand what motivated Gérôme to reject new trends in the arts with such vehemence, you will need to know something about his life and his career. Below is a brief biography of the artist that you need to read and to refer back to as you complete the later parts of the pre-class assignment.

Before you begin reading the passage below, you should take a moment to watch this short video that I have created. It gives you an idea of how to approach readings such as this in a college history course.

Click here to view video

You may also wish to read at a few thoughts that I have created "Thoughts on Reading About Gérôme"In 1840, just as he was turning seventeen, Jean-Léon Gérôme moved from a small provincial city in France to Paris.

The son of the goldsmith, he had demonstrated great aptitude in both the classics and the sciences at the local lycée (high school), but, like many youths of the 19th century, his real passion was to become an artist. At the age of fourteen he had begun studying with a local painter, following a torturously systematic course of instruction that began with study of the dimensions and placement of the eyes, nose, mouth, and ears and then moved slowly through painting the entire face, the feet, the hands, etc., until after several years Gérôme was allowed to paint the entire body. His accurate copy of a painting by an established artist finally convinced his father that Jean-Léon might have sufficient talent to go to Paris to begin a career as a painter, although most of the rest of his family feared that he would be lost forever.

The copy that convinced his father also earned Gérôme a place in the atelier (studio) of the well-known painter, Paul Delaroche. In Paris he learned about the technique of oil painting from his master, studied copies of Greek statues, attended classes at the École de Beaux-Arts (the official art school), and copied famous paintings in the Louvre. He became one of the leaders of a new generation of artists, but he and his friends chose to call for new directions within the slow development of Western art, rather than support a major break with tradition. They found the new emphasis on realism appealing, but, unlike more radical painters, such as Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), who abandoned the classical subject matter that had long dominated European painting and focused on scenes of contemporary life, Gérôm

e and his friends sought to apply a new sense of realism to historical and mythological subjects.

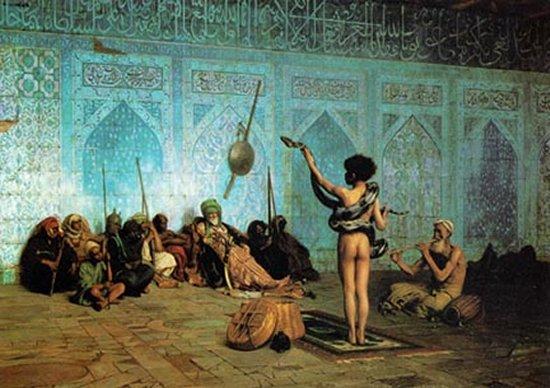

Gérôme mastered the technique of producing a painting that obliterated all traces of brush strokes and produced the illusion of a kind of window on reality. His careful rendering of the human form and concern with historical accuracy appealed to the world of academic art and to potential patrons. The eroticism of much of his work disturbed a few critics, but the fact that most of them were set in other historical periods or cultures made them acceptable to most of his audience.

As years passed Gérôme became increasingly successful. His paintings were regularly accepted into the annual Salons [the yearly exposition of officially approved works of art], and he twice received gold medals. He became a teacher at the École des Beaux Arts [the official art school in Paris], and he received commissions for portraits and for paintings to decorate churches and public buildings. His real love was capturing a moment in time – either by recreating with great detail a moment from a early historical period or by re

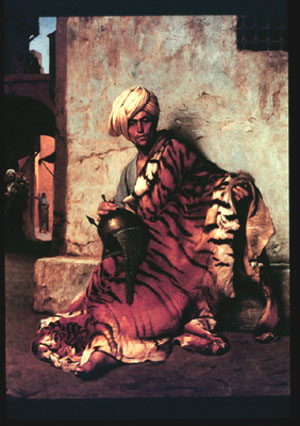

creating exotic visions of daily life in the Islamic world. But he rejected what he called “commonplace and indiscriminate realism” that portrayed everyday scenes without an ennobling or enlightening message.

As he grew older, Gérôme was increasingly out of touch with newer directions in art, and he attacked them strongly. He described Impressionist painting as “insipid and badly executed: badly drawn, badly painted, and stupid beyond expression.” He boasted that “I claim the honor of having waged war against these tendencies, and shall continue to combat them.” In 1884 he objected to a showing of the paintings of Edouard Manet at the École des Beaux Arts, and at the Universal Exhibition of 1900 he is said to have tried to prevent the President of France from entering the Impressionist exhibit, saying “Stop, monsieur le Président, the shame of French painting is in there.” And late in his career he unsuccessfully sought to prevent the entry of women students into the École des Beaux Arts.

By the time of his death at the age of 79 in 1904 Gérôme was clearly out of touch with contemporary developments in art, but his conservative views on modern art represented those of a significant portion of the French art public, and the 57 years that he had been exhibiting at the Salon and the 40 years he taught at the École des Beaux Arts had had a significant impact on the art of the second half of the 19th century.

Gérôme, The Snake Charmer (c.1883)

Gérôme, Pelt Merchant of Cairo

(1869)

To see more paintings that Gérôme would react positively or negatively to, click here.

Jean Leon Gerome Pygmalion and Galatea 1890

The Studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme. Engraving from: L'Illustration, 17 April 1886