June Days and The Revolution of 1848

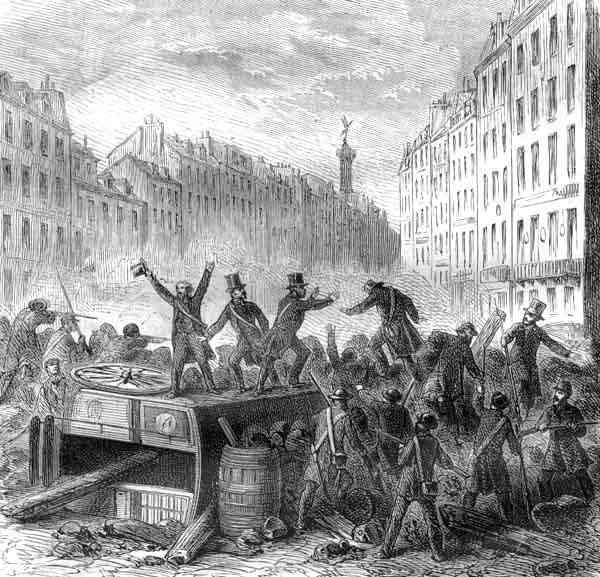

In Paris the coming of the Republic was greeted with "a carnival-like exuberance," according to Gustave Flaubert 's sympathetic recollection, and "enjoyment of a On 23 June, rioting began once more in Paris, and by the evening the whole eastern half of the city was in the hands of insurrectionists. Yet again the revolt was ill prepared, in effect a spontaneous insurrection against hunger and misery. But this time the government was ready for trouble. General Louis-Eugene Cavaignac, Minister of War and another successful pacifier in Algeria, had for some time been drawing up a battle plan against the "Reds,"* and was now invested with almost dictatorial powers. He spent a day bringing in 30,000 regular troops from outside the city, while the rebels constructed their barricades. The following day Cavaignac attacked, deploying his artillery without compunction against the barricades. The rebels fought back sullenly, without leaders, without cheers, and almost without hope. The killing was quite ruthless, but the battle continued for three days. When, most courageously, the Archbishop of Paris, Monsignor Affre, tried to intervene, he was mortally wounded. (The Archbishop of Paris died of wounds sustained on the barricades while attempting to mediate. A successor archbishop was taken hostage and executed by the Commune twenty-three years later.)

|

When it was all over, relieved bourgeois [members of the middle class] and dandies from the western arrondissements came out to inspect the havoc. From his exile in England, LouisPhilippe, recalling how few deaths had brought about his fall, commented with bitter irony that the Republic was lucky "to be able to fire upon the people." June 1848 had unleashed the most sanguinary fighting that had yet been seen on the streets of Paris. Yet the spectacle of a republic butchering its own supporters in a way that no French monarchy or empire could rival would be repeated, with even more hideous consequences, twenty-three years later under the Commune of Paris. The June Days had only created a new generation of embittered Parisians. Following Cavaignac's intervention the military were indisputably masters of Paris, though the Second Republic limped on. There were elections for the presidency. A dark horse in the shape of Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon I, emerged from exile and, backed by provinces and a middle class dismayed by recent events, won three-quarters of the total vote. This was, in fact, a massive vote against Paris. Louis Napoleon collected five and a half million votes to Cavaignac's million and a half; while Ledru-Rollin, the socialist candidate, polled only 370,000, and the poet Lamartine fewer than 8,ooo. Louis Napoleon, remarked Thiers scathingly in private, was "A cretin whom we will manage." But this was soon to prove something of an exaggeration. While in exile in England, the new President of France had enrolled as a special constable during the London troubles. There he had studied carefully, at first hand, how an authoritarian figure like the Duke of Wellington could outflank the revolutionaries and bring to heel a great city. For the best part of two years, former Special Constable Bonaparte trod warily, and kept his counsel. On the evening of 1 December 1851, with great calm and betraying no emotion, he received guests at the Elysee, now the presidential palace, on the Faubourg SaintHonoré. After the last guest had left, he opened a file labeled "Rubicon" obsessed, like his uncle [Napoleon I], by the memory of Caesar. [At a crucial moment in Roman history Julius Caesar had crossed the Rubicon River against orders from the Roman Republic and set himself on the path to becoming dictator.] At dawn in a surprise coup, and under pretext of monarchist threats, his troops occupied key positions in Paris. It was the anniversary both of Austerlitz [one of the original Napoleon’s successful battles] and of his uncle's coronation as emperor; again like his uncle, Louis Napoleon trusted in augury. In contrast to the revolts of 1848, fewer than 400 Parisians were killed. One of the dead was a courageous Deputy, Dr. Baudin, who gained immortality by rashly climbing atop a barricade to proclaim, "See how a man dies for twenty-five francs a day!"*and was promptly felled by three bullets. A further 26,000 "enemies of the regime" were later arrested and transported on the hulks. On 20 December, a plebiscite confirmed the latest Bonapartist coup by a huge majority of nearly seven and a half million to 650,000. A Te Deum was sung in Notre-Dame. Twenty years later the French electorate would painfully agree with Thiers that Louis Napoleon was a crétin –though he had most certainly not proved “manageable.” Meanwhile, however, the Second Empire had arrived.

|

Louis Napoleon |

Proclamation of the 2nd Republic by the Poet Lamartine, February 25, 1848

sort of camp life; nothing was more entertaining than this aspect of Paris during the first days." But the mood swiftly changed as reality replaced fantasy. Unemployment in the capital spiraled up to the previously unheard-of total of 180,000. To bring matters to a head, the new (Republican) government, nominally of "the people," dissolved the national workshop (atelier) scheme designed to provide work for the unemployed, on useless earthworks. From the ateliers left-wing political "clubs" mushroomed throughout the city, their members studying with interest the revolts that had swept the rest of Europe-especially the heroic but futile Polish uprisings.

sort of camp life; nothing was more entertaining than this aspect of Paris during the first days." But the mood swiftly changed as reality replaced fantasy. Unemployment in the capital spiraled up to the previously unheard-of total of 180,000. To bring matters to a head, the new (Republican) government, nominally of "the people," dissolved the national workshop (atelier) scheme designed to provide work for the unemployed, on useless earthworks. From the ateliers left-wing political "clubs" mushroomed throughout the city, their members studying with interest the revolts that had swept the rest of Europe-especially the heroic but futile Polish uprisings. Killed, too, were no fewer than five of Cavaignac's generals, as well as hundreds of unarmed civilians. Official figures -- though these were almost certainly a gross underestimate -- put the deaths at 914 among the government troops and 1,435 for the insurgents. A police commissioner counted fifteen large furniture vans piled high with corpses; many were "shot while escaping," or summarily executed in the quarries of Montmartre or the Buttes-Chaumont in eastern Paris. The Rue Blanche reeked with rotting cadavers hastily interred in the Montmartre cemetery. The details of 1,616 Parisians captured after the 'June Days" were listed in the official records; thousands were arrested and transported to the colonies, or to Algeria, without trial. Flaubert provides a grim picture of one of the dungeons: "Nine hundred men were there, crowded together in filth pellmell, black with powder and clotted blood, shivering in fever and shouting in frenzy. Those who died were left to lie with the others."

Killed, too, were no fewer than five of Cavaignac's generals, as well as hundreds of unarmed civilians. Official figures -- though these were almost certainly a gross underestimate -- put the deaths at 914 among the government troops and 1,435 for the insurgents. A police commissioner counted fifteen large furniture vans piled high with corpses; many were "shot while escaping," or summarily executed in the quarries of Montmartre or the Buttes-Chaumont in eastern Paris. The Rue Blanche reeked with rotting cadavers hastily interred in the Montmartre cemetery. The details of 1,616 Parisians captured after the 'June Days" were listed in the official records; thousands were arrested and transported to the colonies, or to Algeria, without trial. Flaubert provides a grim picture of one of the dungeons: "Nine hundred men were there, crowded together in filth pellmell, black with powder and clotted blood, shivering in fever and shouting in frenzy. Those who died were left to lie with the others."