Eugen Weber, France: Fin de Siècle -- The Science of Decline (2)

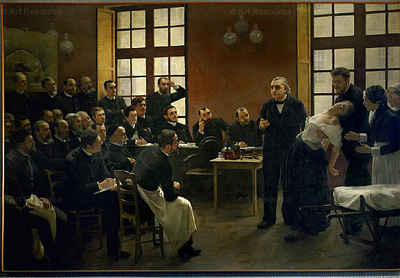

Andre Brouillet. Charcot demonstrating hysteria at La Salpetrie. 1887 |

All these were reinforced in the second half of thecentury by Darwinian notions of biological preselection . It was not simply that men were unequal, but that inequalities were hereditary. Not meritocracy but predetermined elitism traced the destinies of men and societies. So what was the use of effort? Degeneration lay in wait for the predestined, and the social problem confirmed the personal threat. Revulsion and fear: of masses "democratized and syphilitic,"29 of democracy, assimilated to mediocrity, to mongrelization, and eventually to "degeneration."30 They run into each other as through a set of communicating vessels.

The 1840s had seen the popularization of social studies that documented and dramatized widespread misery and its pathological causes: malady and crime. Like malformation and mortality, delinquency and madness became high priorities of public debate, the more challenging for being treated as contagious illnesses for which there had to be a cure. What Roger Williams calls the medical wellsprings of despair could affect more than his exceptional heroes. The guilt and anxiety they produced had social consequences, symbolized by the new professorial chairs set up to study insanity ( 1878) and the diseases of the nervous system ( 1882) and reaffirmed by the data which, beginning with the 1880s, compulsory primary schooling forced on the attention of the public.31 Hordes of "abnormal" children, revealed by new surveys and statistics, testified to an abnormal society, about to be overwhelmed by its misfits, and condemned it as degenerate. Nor did the unexpected scale of physical disgrace revealed by the bustling activity in the realm of public education and hygiene affect the disinherited alone.

The confusion was natural and easy between that hysteria of the lower classes studied and publicized by

Patient of Charcot |

Professor Charcot of the Faculty of Medicine . . . and more fashionable neuroses. One reinforced the other. In 1880 an American medical man, Dr. George Miller . Beard, had published a paper on "Nervous Exhaustion (neurasthenia)," which, supplemented by additional chapters on American Nervousness (New York, 1881), was soon translated into French (1882). This "nerve weakness," to which housewives and young adults appeared particularly prone, manifested itself in physical and mental lassitude, listlessness, lack of energy and enthusiasm, and a general sense of weariness. What the naive and the uninstructed might take for the familiar lineaments of boredom were being promoted into a neurosis appropriate to the better-off, and one whose symptoms admirably fit the pathology of the decade.