Chapter IV -- The Death of A Turtle

In this, one of the best known passages in late 19th century French literature, Huysman's character, des Esseintes, carries the Decadent impulse to choose art over nature to an extreme. This is "art-for-art's-sake" carried to its limits.

It is also interesting to notice how far be goes to prevent contamination from the masses by only consuming the most unusual and essoteric items.

A CARRIAGE stopped late one afternoon before the house at Fontenay. As Des Esseintes never received a  visitor; as even the postman did not venture within these deserted precincts, never having either newspaper, review or letter to leave there, the servants hesitated, asking themselves if they ought to open. But presently, at the repeated summons of the bell outside the wall pulled with a vigorous hand, they went so far as to draw aside the judas let into the door; this done, they beheld a Gentleman whose whole breast was covered, from neck to waist, with a vast buckler of gold.

visitor; as even the postman did not venture within these deserted precincts, never having either newspaper, review or letter to leave there, the servants hesitated, asking themselves if they ought to open. But presently, at the repeated summons of the bell outside the wall pulled with a vigorous hand, they went so far as to draw aside the judas let into the door; this done, they beheld a Gentleman whose whole breast was covered, from neck to waist, with a vast buckler of gold.

They informed their master, who was at breakfast.

"By all means," said he, "bring the gentleman in," — for he remembered having on one occasion given his address to a lapidary to enable the man to deliver an article he had ordered.

The Gentleman came in, made his bow and deposited in the dining-room, on the pitch-pine flooring, his gold shield, which swayed backwards and forwards, rising a little bit from the ground and extending at the extremity of a snake-like neck a turtle’s head which next instant it drew back in a scare under its shell.

This turtle was the result of a whim that had suddenly occurred to Des Esseintes a short while before his leaving Paris Looking one day at an Oriental carpet with iridescent gleams of colour and following with his eyes the silvery glints that ran across the web of the wool, the colours of which were an opaque yellow and a plum violet, he had told himself: it would be a fine experiment to set on this carpet something that would move about and the deep tint of which would bring out and accentuate these tones.

Possessed by this idea, he had strolled at random through the streets; had arrived at the Palais-Royal, and in front of Chevet’s window had suddenly struck his forehead, — a huge turtle met his eyes there, in a tank. He had bought the creature; then, once it was left to itself on the carpet, he had sat down before it and gazed long at it, screwing up his eyes.

Alas! there was no doubt, the negro-head hue, the raw sienna tone of the shell dimmed the sheen of the carpet instead of bringing out the tints; the dominant gleams of silver now barely showed, clashing with the cold tones of scraped zinc alongside this hard, dull carapace.

He gnawed his nails, searching in vain for a way to reconcile these discordances, to prevent this absolute incompatibility of tones. At last he discovered that his original notion of lighting up the fires of the stuff by the to-and-fro movements of a dark object set on it was mistaken; the fact of the matter was, the carpet was still too bright, too crude, too new-looking. Its colours were not sufficiently softened and toned down; the thing was to reverse the proposed expedient, to deaden the tints, to stifle them by the contrast of a brilliant object that should kill everything round it, casting the flash of gold over the pale sheen of silver. Thus looked at, the problem was easier to solve. Accordingly he resolved to have his turtle’s back glazed over with gold.

Once back from the jeweller’s who had taken it in to board at his workshop, the beast blazed like a sun in splendour, throwing its flashing rays over the carpet, whose tones were weak and cold in comparison, looking for all the world like a Visigothic targe inlaid with shining scales, the handiwork of some Barbaric craftsman.

At first, Des Esseintes was enchanted with the effect; but he soon came to the conclusion that this gigantic jewel was only half finished, that it would not be really complete and perfect till it was incrusted with precious stones.

He selected from a collection of Japanese curios a design representing a great bunch of flowers springing from a thin stalk, took it to a jeweller’s, sketched out a border to enclose this bouquet in an oval frame, and informed the dumb-founded lapidary that every leaf and every petal or the flowers was to be executed in precious stones and mounted in the actual scales of the turtle.

The choice of the stones gave him pause; the diamond had grown singularly hackneyed now that every business man wears one on his little finger; Oriental emeralds and rubies are less degraded and dart fine, flashing lights, but they are too reminiscent of those green and red eyes that shine as head-lights on certain lines of Paris omnibuses; as for topazes, burnt or raw, they are cheap stones, dear to the humble housewife who loves to lock up a jewel-case or two in a glasscupboard; of another sort, the amethyst, albeit the Church has given it something of a sacerdotal character, is yet a stone spoilt by its frequent use to ornament the red ears and bulbous hands of butchers’ wives who are fain at a modest cost to bedeck their persons with genuine and heavy jewels. Alone among all these, the sapphire keeps its fires inviolate, unharmed by the folly of tradesmen and money-grubbers. The brilliance of its fire that sparkles from a cold, limpid background has to some degree guaranteed against defilement its discreet and haughty nobility. But unfortunately by artificial light its bright flames flash no longer; the colour sinks back into itself and seems to go to sleep, only to wake and sparkle again at daybreak.

The choice of the stones gave him pause; the diamond had grown singularly hackneyed now that every business man wears one on his little finger; Oriental emeralds and rubies are less degraded and dart fine, flashing lights, but they are too reminiscent of those green and red eyes that shine as head-lights on certain lines of Paris omnibuses; as for topazes, burnt or raw, they are cheap stones, dear to the humble housewife who loves to lock up a jewel-case or two in a glasscupboard; of another sort, the amethyst, albeit the Church has given it something of a sacerdotal character, is yet a stone spoilt by its frequent use to ornament the red ears and bulbous hands of butchers’ wives who are fain at a modest cost to bedeck their persons with genuine and heavy jewels. Alone among all these, the sapphire keeps its fires inviolate, unharmed by the folly of tradesmen and money-grubbers. The brilliance of its fire that sparkles from a cold, limpid background has to some degree guaranteed against defilement its discreet and haughty nobility. But unfortunately by artificial light its bright flames flash no longer; the colour sinks back into itself and seems to go to sleep, only to wake and sparkle again at daybreak.

No, not one of these stones satisfied Des Esseintes; besides, they were all too civilized, too familiar. He preferred other, more startling and uncommon, sorts. After fingering a number of these and letting them trickle through his hands, he finally picked out a series of stones, some real, some artificial, the combination of which should produce a harmony, at once fascinating and disconcerting.

He combined together the several parts of his bouquet in this way: the leaves were set with stones of a strong and definite green colour, — chrysoberyls, asparagus green; peridots, leek green; olives, olive green, springing from twigs of almandine and ouvarovite of a purple red, gems throwing out sparkles of a clear, dry brilliance like the incrustations of tartar that glitter on the insides of wine-casks.

For the blossoms that stood isolated, far removed from the stalk, he used an ashen blue, rejecting, however, definitely the Oriental turquoise that is used for brooches and rings, and which, along with the commonplace pearl and the odious coral form the delight of vulgar souls; he selected exclusively those European turquoises that, strictly speaking, are only a fossil ivory impregnated with coppery infiltrations and whose sea-green blue is heavy, opaque, sulphurous, as if jaundiced with bile.

This done, he could now proceed to incrust the petals of such blossoms as grew in the middle of the bunch, those in closest neighbourhood of the stem, with certain translucent stones, possessing a glassy, sickly sheen with feverish, vivid bursts of fire.

Three gems, and only three, he employed for this purpose, — Ceylon cat’s-eyes, cymophanes and sapphirines.

All three were stones that flashed with mysterious, incalculable sparkles, painfully drawn from the chill interior of their turbid substance, — the cat’s eye of a greenish grey, striped with concentric veins that seem to be endowed with motion, to stir and shift every instant according to the way the light falls; the cymophane with bluish waterings running across the milky hue that appears afloat within; the sapphirine that lights up blue, phosphorescent fires on a dull, chocolate-brown background.

The lapidary took careful notes and measures as to the exact places where the stones were to be let in. "And the edges of the shell?" he presently asked Des Esseintes.

The latter had thought at first of a border of opals and hydrophanes. But these stones, interesting as they are by their curious variations of colour and changes of sparkle, are too difficult and untrustworthy to deal with; the opal has a quite rheumatic sensitiveness, the play of its rays is entirely modified according to the degree of moisture, and of heat and cold, while the hydrophane has no fire, refuses to light up the grey glow of its furnace except in water, after it has been wetted.

Finally he settled on stones whose hues would supplement each other, — the hyacinth of Compostella, mahogany red; the aquamarine, sea green; the balass ruby, vinegar rose; the Sudermania ruby, pale slate-colour. Their comparatively feeble play of colours would suffice to light up the deadness of the dull, grey shell, while leaving its full value to the brilliant bouquet of jewelled blossoms which they framed in a slender garland of uncertain splendours.

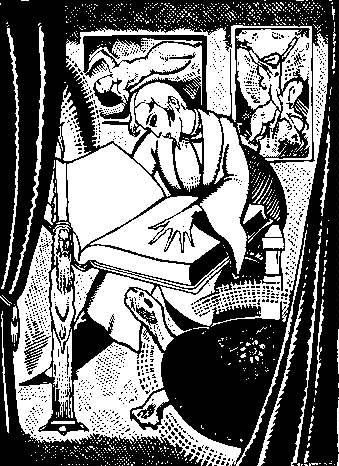

Des Esseintes stood gazing at the turtle where it lay huddled together in one corner of the dining-room, flashing fire in the dim half light.

He felt perfectly happy; his eyes were intoxicated with the splendours of these flowers flashing in jewelled flames against a golden background. . . .

Outside the snow was falling. In the lamplight, ice arabesques glittered on the dark windows and the hoar-frost sparkled like crystals of sugar on the bottle-glass panes speckled with gold.

A deep silence wrapped the little house that lay asleep in the darkness.

Des Esseintes stood lost in dreams; the logs burning on the hearth filled the room with hot, stifling vapours, and presently he threw the window partly open. . . .

He sprang up to break the horrid nightmare of his thoughts, and coming back to everyday matters, began to feel anxious about the turtle.

It still lay quite still; he touched it, it was dead. Accustomed no doubt to a sedentary life, an uneventful existence spent under its humble carapace, it had not been able to support the dazzling splendour imposed on it, the glittering garment in which it had been clad, the pavement of precious stones wherewith they had inlaid its poor back like a jewelled pyx.

J.K. Huysman's Tomb in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris