The Art of Drinking

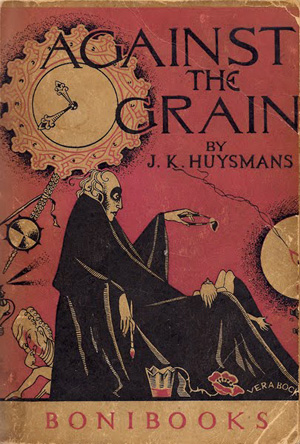

Decadent artists and intellectuals were often obsessed with turning every art into a work of art. In these two passages Huysmans describes how des Esseintes transforms the natural act of drinking into a highly artificial art form. At the same time des Esseintes is also distancing himself from the masses by his esoteric choices.

Then, contrary to his use, he had an appetite and was dipping his slices of toast spread with super-excellent  butter in a cup of tea, an impeccable blend of Si-a-Fayoun, Mo-you-tann and Khansky, — yellow teas, imported from China into Russia by special caravans.

butter in a cup of tea, an impeccable blend of Si-a-Fayoun, Mo-you-tann and Khansky, — yellow teas, imported from China into Russia by special caravans.

This liquid perfume he drank from those cups of Oriental porcelain known as egg-shell china, so delicate and transparent are they; in the same way, just as he would have nothing to say to any other save this adorably dainty ware, he refused to use as dishes and plates anything else but articles of genuine antique silver-gilt, a trifle worn so that the underlying silver shows a little here and there under the film of gold, giving a tender, old-world look as of something fading away in a quiet death of exhaustion.

After swallowing his last mouthful, he went back to his study, whither he directed a servant to bring the turtle, which obstinately declined to make the smallest effort towards locomotion. . . .

He made his way to the dining-room, where in a recess in one of the walls, a cupboard was contrived, containing a row of little barrels, ranged side by side, resting on miniature stocks of sandal wood and each pierced with a silver spigot in the lower part.

This collection of liquor casks he called his mouth organ. A small rod was so arranged as to connect all the spigots together and enable them all to be turned by one and the same movement, the result being that, once the apparatus was installed, it was only needful to touch a knob concealed in the panelling to open all the little conduits simultaneously and so fill with liquor the tiny cups hanging below each tap.

The organ was then open. The stops, labelled "flute," "horn," "vox humana," were pulled out, ready for use. Des Esseintes would imbibe a drop here, another there, another elsewhere, thus playing symphonies on his internal economy, producing on his palate a series of sensations analogous to those wherewith music gratifies the ear.

Indeed, each several liquor corresponded, so he held, in taste with the sound of a particular instrument. Dry curacao, for instance, was like the clarinet with its shrill, velvety note; kummel like the oboe, whose timbre is sonorous and nasal; creme de menthe and anisette like the flute, at one and the same time sweet and poignant, whining and soft. Then, to complete the orchestra, comes kirsch, blowing a wild trumpet blast; gin and whisky, deafening the palate with their harsh outbursts of comets and trombones; liqueur brandy, blaring with the overwhelming crash of the tubas, while the thunder peals of the cymbals and the big drum, beaten might and main, are reproduced in the mouth by the rakis of Chios and the mastics.

He was convinced too that the same analogy might be pushed yet further, that quartettes of stringed instruments might be contrived to play upon the palatal arch, with the violin represented by old brandy, delicate and heady, biting and clean-toned; with the alto, simulated by rum, more robust, more rumbling, more heavy in tone; with vespetro, long-drawn, pathetic, as sad and tender as a violoncello; with the double-bass, full-bodied, solid and black as a fine, old bitter beer. One might even, if anxious to make a quintette, add yet another instrument, — the harp, mimicked with a sufficiently close approximation by the keen savour, the silvery note, clear and self-sufficing, of dry cumin.

Nay, the similarity went to still greater length, analogies not only of qualities of instruments, but of keys were to be found in the music of liquors; thus, to quote only one example, Bénédictine figures, so to speak, the minor key corresponding to the major key of the alcohols which the scores of wine-merchants’ price-lists indicate under the name of green Chartreuse.

These assumptions once granted, he had reached a stage, thanks to a long course of erudite experiments, when he could execute on his tongue a succession of voiceless melodies; noiseless funeral marches, solemn and stately; could hear in his mouth solos of crême de menthe, duets of vespetro and rum.

He even succeeded in transferring to his palate selections of real music, following the composer’s motif step by step, rendering his thought, his effects, his shades of expression, by combinations and contrasts of allied liquors, by approximations and cunning mixtures of beverages.

Sometimes again, he would compose pieces of his own, would perform pastoral symphonies with the gentle blackcurrent ratafia that set his throat resounding with the mellow notes of warbling nightingales; with the dainty cacao-chouva, that sung sugarsweet madrigals, sentimental ditties like the "Romances d’Estelle"; or the "Ah! vous di-rai-je maman," of former days.