Anne Maxwell, “Colonial Photography and Exhibitions”

The period from 1850 to 1915, sometimes known as the age of high imperial ism, witnessed the birth of two types of mass-produced images of colonized peoples that were to have a powerful impact on the way in which non-westerners have been portrayed in twentieth -century popular culture. These were the live displays of allegedly 'primitive' peoples that were staged at the Great Exhibitions in the metropolitan centres, and the photographic images of non-western peoples that formed part of an emerging international tourist industry. Because these representations relied predominantly on visual means of communication, they conveyed the idea of colonized peoples’ primitiveness to more Europeans than either colonial fiction or travel writing, and did so with greater force and emotional impact.

Inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego on exhibit at the Jardin d'Acclimation in Paris |

Most of these images were racist in tone, and inflicted physical ; and sychological injuries on the participating individuals, their numerous descendants and the communities from which they were drawn. Yet the damage was not limited to the people who were on the receiving end of the imperial gaze. Images of colonized peoples also had an effect on the predominantly western audiences who consumed them. The visual representation of colonized peoples as savages not only helped to sustain imperialist expansion but also supplied Europeans with a new, empowering framework for identity based on racial and cultural essences, the effects of which are still evident today in the exploitative and discriminatory attitudes that continue to surface within metropolitan and settler-colonial societies. Without a knowledge of the way in which such popular representations of non-western peoples contributed to the formation of European identities, people of European descent cannot begin to imagine - let alone contribute to fashioning - a world in which the ideology of white supremacy no longer informs dominant culture. . .

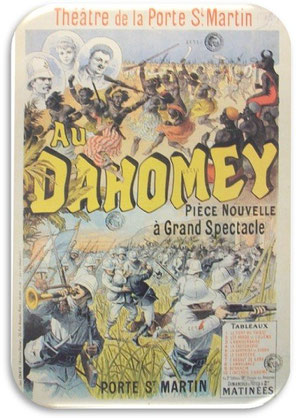

Among the exhibits regularly featured at nineteenth-century international exhibitions, or 'world's fairs' as they became known in North America, few were more popular than live displays of colonized peoples. The emergence of such displays in international exhibitions coincided with the renewal of European imperial expansion during the second half of then nineteenth century. These displays not only drew massive crowds but also claimed an educative function and gained the imprimatur of contemporary scientific theories of race. . .

The decision to display colonized peoples coincided with the public’s growing interest in scientific theories about the origins of the

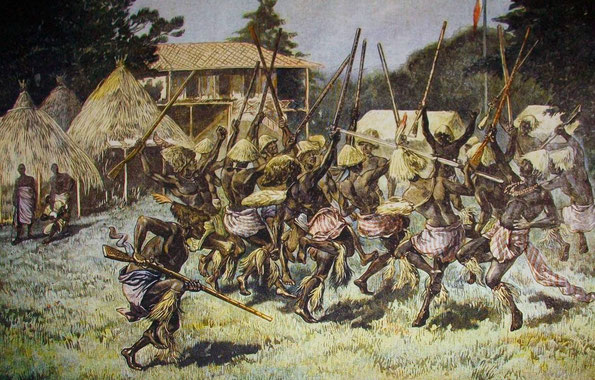

Warriors from the Ivory Coast acting out the role of warrior in the Jardin d'Accolimation in Paris |

different races. No less than the botanical and zoological specimens that preoccupied Victorian scientists, colonized peoples were exposed to hierarchical systems of classification. In deference to the public's preference for pleasurable forms of education, however, exhibition managers also exploited time-worn myths about practices such as cannibalism and prostitution, through which the colonized were portrayed as flouting the taboos associated with civilization. As well as enlivening the displays, these myths allowed Europeans to deflect the violence they had inflicted on 'native' populations back onto the people whose resources they were exploiting, whose lands they were occupying and whose cultures they were undermining. . .

The problem was that colonialism was founded on a basic contradiction: on the one side was a rhetoric proclaiming that the colonized possessed the capacity to become civilized, where on the other was a political and economic agenda that depended on exclusiveness and the myth of racial purity. The makers of the exhibitionary displays could only disguise this paradox by replacing the concrete realities of colonialism with imaginary representations based on the dream of absolute control. As Raymond Corbey has wryly remarked, the narrative constructed by the exhibitions was bound to be popular with Europeans, if only because they composed the script and performed the leading roles:

Displays of colonized peoples were convened by eminent anthropologists attached to prestigious museums and scientific institutions. This, together with the high calibre of the sponsors, ensured that the exhibits were regarded as authentic. I n England, exhibitions were supported by royalty, the peerage, members of parliament and other prominent citizens. Similarly, in France, sponsors included prominent political leaders and the elite within the republican movement. . . . The fact that invitations to overseas performers tended to be issued through official channels also helped to protect the exhibitions from the accusations of inauthenticity that were frequently directed at displays of non-western peoples staged by showmen and circuses. Finally, the respectability of the anthropological displays was assured by promoters associating themselves with a group of legitimate educational institutions known as the exhibitionary complex. This comprised the museums of natural science, history and art which were the legacy of earlier moves by the state to improve the aesthetic taste of the general public by replacing fairground pleasures with the more 'elevated' activity of museum-going. . . .

Displays of colonized peoples were convened by eminent anthropologists attached to prestigious museums and scientific institutions. This, together with the high calibre of the sponsors, ensured that the exhibits were regarded as authentic. I n England, exhibitions were supported by royalty, the peerage, members of parliament and other prominent citizens. Similarly, in France, sponsors included prominent political leaders and the elite within the republican movement. . . . The fact that invitations to overseas performers tended to be issued through official channels also helped to protect the exhibitions from the accusations of inauthenticity that were frequently directed at displays of non-western peoples staged by showmen and circuses. Finally, the respectability of the anthropological displays was assured by promoters associating themselves with a group of legitimate educational institutions known as the exhibitionary complex. This comprised the museums of natural science, history and art which were the legacy of earlier moves by the state to improve the aesthetic taste of the general public by replacing fairground pleasures with the more 'elevated' activity of museum-going. . . .

In France, anthropological displays were designed to gain tacit approval for colonialism by introducing the public to the fundamentals of the progressivist version of evolution. The first French international Exhib1tion to contain human exhibits was the Pans Exposition Universelle of 1867, where foreign peoples from France's North African territories were recruited as labourers for the building sites and as vendors, waiters and waitresses for the shops, cafes and restaurants. The exhibits included an Egyptian bazaar and a Tunisian barber's shop, which was open for business. V1s1tors to the site were more fascinated by the foreign workers than the exotic objects they were peddling. Observing this, organizers of the subsequent exhibition in 1878 decided to include an Algerian bazaar and a Cairo street among their displays.

Between that exh1b1tion and the next in 1889, an important intellectual shift took place. As a result of the Pans Academy's [This is not the Academy of Arts] decision to accept anthropology as a discipline, attention was directed away from the Orient towards what were perceived as the 'primitive' cultures of Africa, Oceania and Australia. The first displays of peoples from these regions were held in a verdant space near the exhibition grounds known as the Jardin d'Acclimation. Established in the Bois de Boulogne in 1859 as a centre for the study of botany and zoology, the Jardin d Acclimation offered the public an opportunity to peruse the world's most exotic plants and animals in a metropolitan environment. Attendance was small in the early years, but the number of visitors swelled in 1877 when a par ty of Nub1ans was included in the programme. The organizers subsequently arranged to show six Eskimos, and when this exhibit too proved remarkably popular they embarked on bringing people from all over the world to be displayed alongside the animals.