Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man (New York: W.W.Norton, 1981), pp.82-87.

Masters of craniometry: Paul Broca and his school

It is often difficult for us to remember that notions of race and heredity that sound utterly ridiculous to us today were supported in the late 19th century by some of the finest scientists in France. Since these ideas had a major impact on how Parisians viewed their world, it is worth exploring the pseudo-science of one of the founders of modern brain science, Paul Broca. Here 20th century biologist and historian of science, Stephen J. Gould presents and critiques Broca's views.

In 1861 a fierce debate extended over several meetings of a young association still experiencing its birth pangs. Paul Broca 1824-1880), professor of clinical surgery in the faculty of medicine, had founded the Anthropological Society of Paris in 1859. At a meeting of the society two years later, Louis Pierre Gratiolet read a paper that challenged Broca's most precious belief: Gratiolet dared to argue that the size of a brain bore no relationship to its degree of intelligence.

In 1861 a fierce debate extended over several meetings of a young association still experiencing its birth pangs. Paul Broca 1824-1880), professor of clinical surgery in the faculty of medicine, had founded the Anthropological Society of Paris in 1859. At a meeting of the society two years later, Louis Pierre Gratiolet read a paper that challenged Broca's most precious belief: Gratiolet dared to argue that the size of a brain bore no relationship to its degree of intelligence.

Broca rose in his own defense, arguing that "the study of the brains of human races would lose most of its interest and utility" if variation in size counted for nothing (1861, p. 141). Why had anthropologists spent so much time measuring skulls, unless their results could delineate human groups and assess their relative worth? . . .

Broca concluded triumphantly:

In general, the brain is larger in mature adults than in the elderly, in men than in women, in eminent men than in men of mediocre talent, in superior races than in inferior races·(1861, p. 304). . . . Other things equal, there is a remarkable relationship between the development of intelligence and the volume of the brain (p. 188).

Five years later, in an encyclopedia article on anthropology, Broca expressed himself more forcefully:

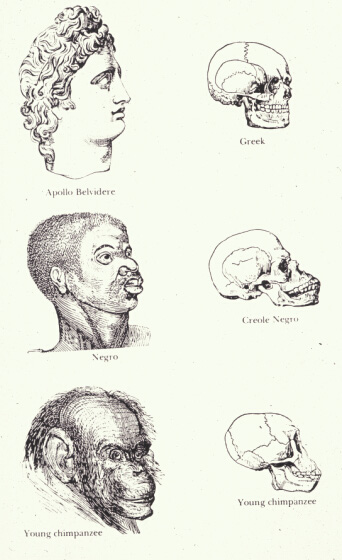

A prognathous [forward-jutting] face, more or less black color of the skin, woolly hair and intellectual and social inferiority are often associated, while more or less white skin, straight hair and an orthognathous [straight] face are the ordinary equipment of the highest groups in the human series (1866, p. 280) . . . . A group with black skin, woolly hair and a prognathous face has never been able to raise itself spontaneously to civilization (pp. 295-296).

These are harsh words, and Broca himself regretted that nature had fashioned such a system (1866, p. 296). But what could he do? Facts are facts. "There is no faith, however respectable, no interest, however legitimate, which must not accommodate itself to the progress of human knowledge and bend before truth" (in Count, 1950, p. 72). Paul Topinard, Broca's leading disciple and successor, took as his motto (1882, p. 748): ''j'ai horreur des systemes et surtout des systemes a priori" (I abhor systems, especially a priori systems).

Broca singled out the few egalitarian scientists of his century for particularly harsh treatment because they had debased their calling by allowing an ethical hope or political dream to cloud their judgment and distort objective truth. "The intervention of political and social considerations has not been less injurious to anthropology than the religious element" (1855, in Count, 1950, p. 73) . . . -page paper analyzing Morton's techniques in the most minute detail-Broca, 1873b.)

Why had Tiedemann gone astray? "Unhappily," Broca wrote (1873b, p. 12), "he was dominated by a preconceived idea. He set out to prove that the cranial capacity of all human races is the same." But "it is an axiom of all observational sciences that facts must precede theories" (1898, p. 4). Broca believed, sincerely I assume, that facts were his only constraint and that his success in affirming traditional rankings arose from the precision of his measures and his care in establishing repeatable procedures.

Indeed, one cannot read Broca without gaining enormous respect for his care in generating data. I believe his numbers and doubt that any better have ever been obtained. Broca made an exhaustive study of all previous methods used to determine cranial capacity . . .

I spent a month reading all of Broca's major work, concentrating on his statistical procedures. I found a definite pattern in his method s. He traversed the gap between fact and conclusion by what may be the usual route -- predominantly in reverse. Conclusions came first and Broca's conclusions were the shared assumptions of most successful white males during his time-themselves on top by the good fortune of nature, and women, blacks, and poor people below. His facts were reliable (unlike Morton's), but they were gathered selectively and then manipulated unconsciously in the service of prior conclusions. By this route, the conclusions achieved not only the blessing of science, but the prestige of numbers. Broca and his school used facts as illustrations, not as constraining documents. They began with conclusions, peered through their facts, and came back in a circle to the same conclusions. Their example repays a closer study, for unlike Morton (who manipulated data, however unconsciously), they reflected their prejudices by another, and probably more common, route: advocacy masquerading as objectivity.

Selecting characters

When the "Hottentot Venus" died in Paris, Georges Cuvier, the greatest scientist and, as Broca would later discover to his delight, the largest brain of France, remembered this African woman as he had seen her in the flesh.

She had a way of pouting her lips exactly like what we have observed in the orang-utan. Her movements had something abrupt and fantastical about them, reminding one of those of the ape. Her lips were monstrously large [those of apes are thin and small as Cuvier apparently forgot]. Her ear was like that of many apes, being small, the tragus weak, and the external border almost obliterated behind. These are animal characters. I have never seen a h u man head more like an ape than that of this woman (in Topinard, i878, pp. 493-494).

The human body can be measured in a thousand ways. Any investigator, convinced beforehand of a group's inferiority, can select a small set of measures to illustrate its greater affinity with apes. (This procedure, of course, would work equally well for white males, though no one made the attempt. White people, for example, have thin lips -- a property shared with chimpanzees-while most black Africans have thicker, consequently more "human," lips.)

Broca's cardinal bias lay in his assumption that human races could be ranked in a linear scale of mental worth. In enumerating the aims of ethnology, Broca included: "to determine the relative position of races in the human series" (in Topinard, i878, p. 660). It did not occur to him that human variation might be ramified and random, rather than linear and hierarchical. And since he knew the order beforehand, anthropometry became a search for characters that would display the correct ranking, not a numerical exercise in raw empiricism.

Thus Broca began his search for "meaningful" characters -- those that would display the established ranks. In 1862, for example, he tried the ratio of radius (lower arm bone) to humerus (upper arm bone), reasoning that a higher ratio marks a longer forearm-a character of apes. All began well: blacks yielded a ratio of .794, whites .739. But then Broca ran into trouble. An Eskimo skeleton yielded .703, an Australian aborigine .709, while the Hottentot Venus, Cuvier's near ape (her skeleton had been preserved in Paris), measured a mere .703. Broca now had two choices. He could either admit that, on this criterion, whites ranked lower than several dark-skinned groups, or he could abandon the criterion. Since he knew ( i862a, p. 10) that Hottentots, Eskimos, and Australian aborigines ranked below most African blacks, he chose the second course: "After this, it seems difficult to me to continue to say that elongation of the forearm is a character of degradation or inferiority, because, on this account, the European occupies a place between Negroes on the one hand, and Hottentots, Australians , and eskimos on the other" (1862, p. 11).

Later, he almost abandoned his cardinal criterion of brain size because inferior yellow people scored so well:

A table on which races were arranged by order of their cranial capacities would not represent the degrees of their superiority or inferiority, because size represents only one element of the problem [of ranking races]. On such a table, Eskimos, Lapps, Malays, Tartars and several other peoples of the Mongolian type would surpass the most civilized people of Europe. A lowly race may therefore have a big brain ( i 873a, p. 38).

But Broca felt that he could salvage much of value from his crude measure of overall brain size. It may fail at the upper end because some inferior groups have big brains, but it works at the lower end because small brains belong exclusively to people of low intelligence. Broca continued:

But this does not destroy the value of small brain size as a mark of inferiority. The table shows that West African blacks have a cranial capacity about 100 cc less than that of European races . To this figure, we may add the following: Caffirs, Nubians, Tasmanians, Hottentots , Australians. These examples are sufficient to prove that if the volume of the brain does not play a decisive role in the intellectual ranking of races, it nevertheless has a very real importance ( i873a, p. 38).

An unbeatable argument. Deny it at one end where conclusions are uncongenial; affirm it by the same criterion at the other. Broca did not fudge numbers; he merely selected among them or interpreted his way around them to favored conclusions.