Richard Thompson, Phillip Denis Cate, and Mary Weaver Chapin, Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre (1)

The Culture of Montmartre

The critique of decadence -- drawing attention to society's class divisions, moral corruption, and sexual exploitation -- came from various quarters. Conservative forces might use it to condemn modernity in relation to the superior values of the past. while the left used it to promote its own radical agenda. 3 The republic reacted defensively. with moralizing propriety allied t o a degree of censorship . This collided with Lautrec's own areas of operation. Songs performed in the cafes -concerts were controlled. Yvette Guilbert being obliged to drop a verse about lesbians from Maurice Donnay's song '"Eros Vanne'" (Clapped-out Cupid), while the song sheet Lautrec designed included that very allusion 4 In 1896. Writing in the establishment Revue des deux mondes Maurice Talmeyr accused contemporary posters of being a corrupting influence, typically modern and decadent in their feverish commercialism and lack of respect for women. religion, and authority, calling for them to promote more elevated values. 5 In riposte. it was argued that the recent proliferation of the multicolored poster was a lively counter to the regime's stuffiness; hitherto the Parisian street had been "straight, regular, chaste. and republican. "6

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec's Illustration for the song "Eros Exhausted," c.1894

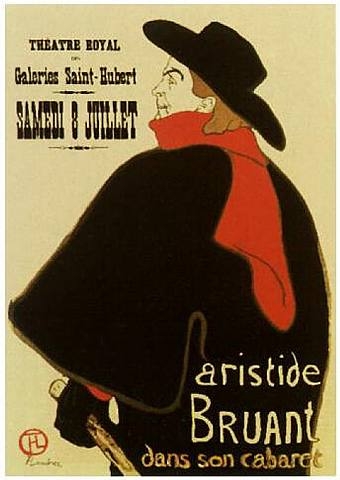

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, Poster for Aristide Bruant's Cabaret (1893)

The decadent critique was central to the "Montmartre" culture of cabarets, illustrated periodicals, and popular song within which Lautrec's work developed and to which it contributed. The easing of the censorship laws in 1881 gave scope for the younger generation's perception of the bourgeois republic as corrupt and venal, stuffy and hypocritical. During the early 1880s Montmartre rapidly developed into the locale where such anti-establishment attitudes were stridently voiced. There were a number of reasons why Montmartre. rather than some other quartier, nurtured this subculture. Its history of independence counted; it had only become officially incorporated into the administration of Paris in 1860, and its record in the Commune gave it a whiff of danger.7 Its lower slopes, nearer the city center, already housed the studios of important artists such as Degas, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and Gustave Moreau, and alongside the studios was an infrastructure of models, dealers in artists' materials, and so on. Toward the top of the Montmartre hill, "the butte," rents were cheaper for younger artists because it was a more proletarian district. and the combination of low life and low cost suited Lauttrec and his peers. Finally, Montmartre already had its vernacular entertainments: workingclass bars and dance halls. And as a porous Frontier where there was seepage between the smarter classes of central Paris and the proletariat of the outer suburbs. where the two might meet in the commerce of leisure and prostitution, it was a habitat where the egalitarian rhetoric of the Third Republic came under scrutiny. Class mixture was less an expression of fraternity than nervous, temporary cross-quartier tourism, less an expression or equality than evidence of the hypocrisy and exploitation of much social exchange. In any event. Montmartre was the ideal terrain for the development of up-to-the-minute cultural forms.