Robert Gildea, Children of the Revolution

The Context of the Arts in the Late 19th Century

The successful writer, artist or musician at the end of the nineteenth century had access to three indispensable resources. The first was connections and patronage,

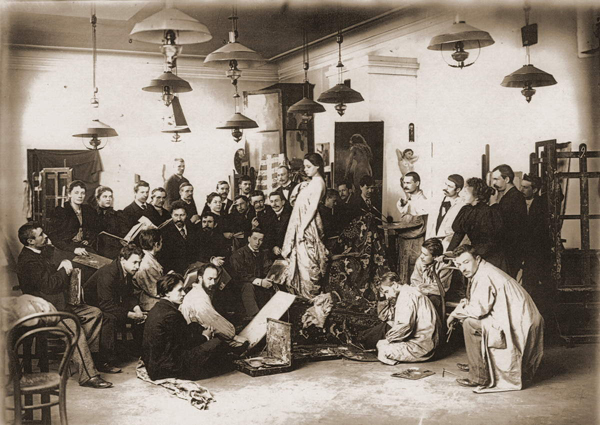

which could further a career, and might be provided by an influential salon in Paris or official recognition in the annual Salon sponsored by the Academie des Beaux Arts or by the prizes and membership of the Academie Française. The second was the dialogue, comradeship and support that could be offered by fellow writers and artists, who often met in favourite cafes and restaurants and reviewed each other's work in journals and newspapers. Conflict between different approaches was common, a sense of betrayal was rife, and friendships often came to a bitter end, but all this was grist to the mill of literary, artistic and musical innovation. The third was public recognition and a market for their work in the growing consumer society. Not every writer or artist had access to all three resources. Official recognition in the Salon or Academie Française was generally confined to those who subscribed to the classical French canon as laid down by those institutions and did not seek radical or avant-garde approaches. Avant-garde writers and artists scorned fficial institutions and canons, or at least affected to do so. They also affected to scorn the demands of the mass market, which they denounced as ignorant and philistine, although they could not entirely eschew the oxygen of publicity and the income to live. For a mass culture was developing, which was something different from both elite culture and popular culture: a culture demanded by a largely urban society, shaped by mass education and craving instruction and entertainment more than cultivation, and supplied by a mass media of books, newspapers, universal exhibitions, music halls, cinemas, sports stadiums and race tracks. Classical and avant-garde or modern art and the mass consumer society were locked in a tension, but the art, literature and bohemian lifestyle of Paris were themselves becoming national assets, widely commented upon in Europe and America and drawing in foreign writers, artists and tourists.