Art Institute of Chicago -- "Toulouse Lautrec and Montmartre"

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), the

quintessential chronicler of the Parisian district of

Montmartre, created some of the most memorable images of the exciting new

culture of late-19th-century France—a culture that was worlds apart from the

artist’s aristocratic upbringing in provincial France. Born in the southern

town of Albi, Lautrec was related to the counts of Toulouse, who had once

ruled over the Languedoc region. Though he was economically privileged,

Lautrec suffered numerous health ailments—likely resulting from the

intermarriage of his parents, who were cousins. Lautrec’s abnormally weak

bones led to multiple leg fractures that stunted his growth and made walking

a lifelong difficulty for him. Barred from many activities, he became a keen

observer, and with his mother’s encouragement he began drawing and painting

in his teenage years.

Montmartre, created some of the most memorable images of the exciting new

culture of late-19th-century France—a culture that was worlds apart from the

artist’s aristocratic upbringing in provincial France. Born in the southern

town of Albi, Lautrec was related to the counts of Toulouse, who had once

ruled over the Languedoc region. Though he was economically privileged,

Lautrec suffered numerous health ailments—likely resulting from the

intermarriage of his parents, who were cousins. Lautrec’s abnormally weak

bones led to multiple leg fractures that stunted his growth and made walking

a lifelong difficulty for him. Barred from many activities, he became a keen

observer, and with his mother’s encouragement he began drawing and painting

in his teenage years.

|

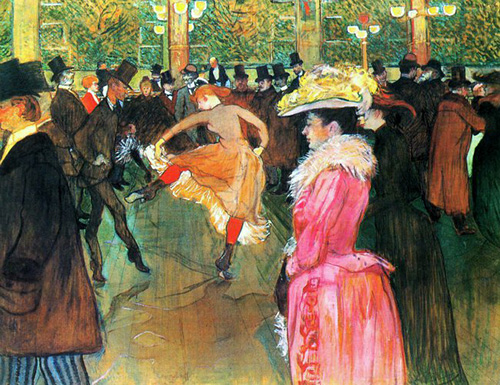

Toulouse-Lautrec, Ball at the Moulin Rouge (1890), |

Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre journeys through the evolution of Lautrec’s short career—from experimental painter to innovative printmaker to contemplative illustrator—demonstrating how his artwork captures the essence of fin-de-siècle Parisian nightlife. His prints, paintings, and drawings in a variety of media are juxtaposed with the work of his predecessors and contemporaries, highlighting not only the Bohemian culture that saturated the district of Montmartre, but also the manner in which older artists such as Edgar Degas influenced Lautrec’s choice of subject matter, framing, lighting, and perspective, and the way that the daring, often racy entertainment industry of Montmartre lured such artists as Vincent van Gogh and Pablo Picasso to the district.

The installation presents certain themes of Lautrec’s work that display both the settings that

|

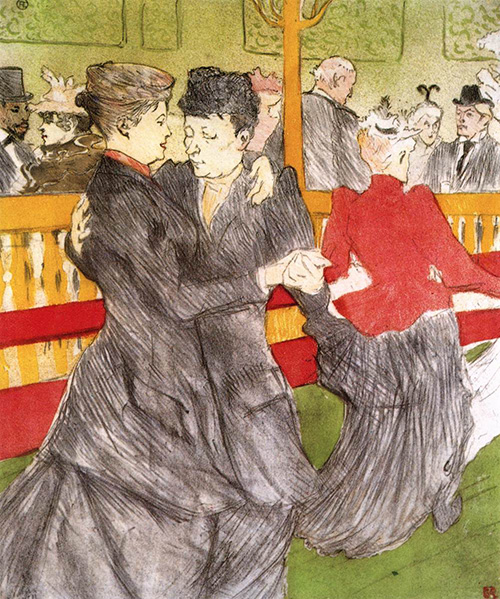

Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge: Two Women Waltzing (1897) |

fascinated him and his uncanny ability to provide psychological insight into the dancers, patrons, and Montmartre celebrities that he portrayed. In his representations of the cabarets, dance halls, café-concerts, celebrity culture, brothels, and circuses he revealed both the public and private sides of Montmartre culture.

Montmartre’s dance halls, cabarets, café-concerts,

brothels, and circuses created a racy, uncensored atmosphere that attracted

working-class residents of the district, as well as thrill-seeking bourgeois

patrons from central Paris and beyond. Set upon a butte, or hill, and

removed from the city center, Montmartre had an identity separate from that

of central Paris, which was then governed by the conservative Third

Republic. The neighborhood attracted artists of all types. Some came seeking

fame and fortune, while others just wished to revel in the Bohemian

atmosphere. For these artists, the vibrant culture of Montmartre, with its

unbridled energy, tawdry behavior, garish colors, and provocative

celebrities, was both a way to live and a subject to depict. Lautrec, who

labeled Montmartre as “outside the law,” immersed himself in this decadent

culture, painting and drawing by day and dwelling in the cafés and cabarets

by night.

|

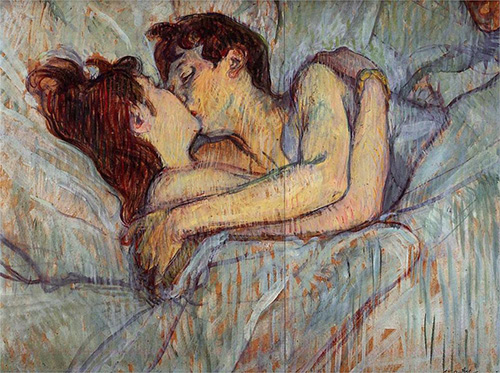

Toulouse-Lautrec, The Kiss (1892) |

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, Montmartre’s dance halls surged in popularity. Some of the most famous venues, including the Moulin de la Galette and the Moulin Rouge, offered a wide variety of entertainment in a carnival-like atmosphere that included acrobats, puppet shows, and animal acts. It was the singers and dancers, however, who were the greatest attractions. Large crowds came to see celebrities such as La Goulue (“the glutton”) perform new dances such as the chahut—a racy, eroticized version of the cancan. Prints such as The Englishman at the Moulin Rouge showcase Lautrec’s libertine stance on Montmartre’s decadent nightlife.

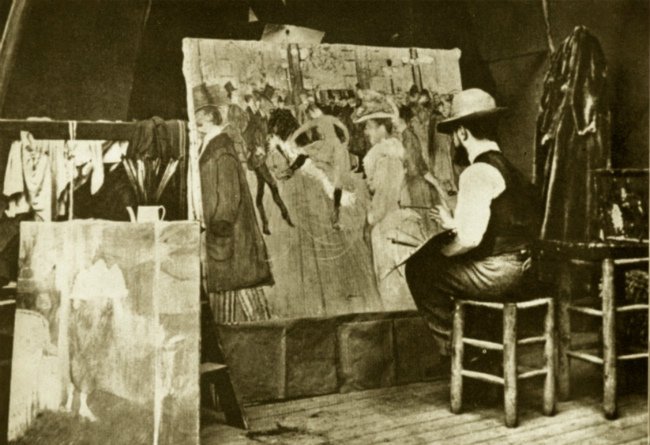

The paintings that Lautrec made of the dance halls of Montmartre are among his most complex works. They constitute the majority of his large, multifigure canvases—works that challenged his compositional skill. At the Moulin Rouge is an unsettling painting with severe lighting, unconventional perspective, and an ambiguous narrative. The performers La Goulue and Jane Avril, as well as Lautrec himself, can be found in this painting. With its skewed perspective, lurid colors, and perplexing social dynamic, At the Moulin Rouge is both alienating and arresting—an embodiment of the spirit of Montmartre. In 1881 the artist-cum-entrepreneur Rodolphe Salis opened a new cabaret called the Chat Noir (“black cat”) at the foot of Montmartre’s hill. The name called to mind Edgar Allen Poe’s perverse and haunting tale by the same title, French folktales, and the poetry of Charles Baudelaire. The black cat—a nocturnal creature that is mysterious, seductive, playful, and independent—became a symbol not only for the Chat Noir itself, but for all of Montmartre. The Chat Noir became a gathering spot for avant-garde artists, poets, musicians, and writers, who used the cabaret as an artistic laboratory to recite poems, sing songs, and exhibit paintings. Publicity posters, made possible by the lithographic technique, were an important innovation of the artists of Montmartre. Lithography, a printing process in which images are drawn on a large stone, allowed Lautrec to utilize a skillful integration of text and image. Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen’s poster Tournée du Chat Noir, featuring a black cat sitting upright with a halo surrounding his head, is an iconographic image of Montmartre. Lautrec’s first foray into printmaking was a resounding success. His print Moulin Rouge: La Goulue fueled the popularity of La Goulue and made Lautrec an overnight sensation in Montmartre.

In 1881 the artist-cum-entrepreneur Rodolphe Salis opened a new cabaret called the Chat Noir

|

Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge |

(“black cat”) at the foot of Montmartre’s hill. The name called to mind Edgar Allen Poe’s perverse and haunting tale by the same title, French folktales, and the poetry of Charles Baudelaire. The black cat—a nocturnal creature that is mysterious, seductive, playful, and independent—became a symbol not only for the Chat Noir itself, but for all of Montmartre. The Chat Noir became a gathering spot for avant-garde artists, poets, musicians, and writers, who used the cabaret as an artistic laboratory to recite poems, sing songs, and exhibit paintings.

Publicity posters, made possible by the lithographic technique, were an important innovation of the artists of Montmartre. Lithography, a printing process in which images are drawn on a large stone, allowed Lautrec to utilize a skillful integration of text and image. Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen’s poster Tournée du Chat Noir, featuring a black cat sitting upright with a halo surrounding his head, is an iconographic image of Montmartre. Lautrec’s first foray into printmaking was a resounding success. His print Moulin Rouge: La Goulue fueled the popularity of La Goulue and made Lautrec an overnight sensation in Montmartre.

The maisons closes ("closed houses")—the French euphemism for brothels—were licensed establishments where authorities could discretely regulate prostitution. Police periodically monitored the premises while prostitutes, who officially registered with one of the maisons closes, were subject to routine medical inspections.

Lautrec, a social outsider, seemed to find comfort in the sexual subculture, even boasting to friends that he had lived for a time in a brothel (an unproven claim). Between the mid-1880s and mid-1890s, Lautrec produced some 50 paintings on the theme of prostitution, none of which was publicly exhibited during his lifetime. Only Elles, his 1896 album of 11 color lithographs that depicts the daily routines of prostitutes, was published.

Lautrec’s representations of the world of prostitution evince a real sympathy for the women; however, the works are also dominated by a matter-of-fact mentality. The women are seen as both sensual and alluring and as surviving under trying social circumstances. The prostitutes are shown awaiting clients, submitting to medical exams, lying on beds, and embracing. In the Salon: The Sofa illustrates a group of prostitutes in a maison close seated upon a red divan, awaiting their clients. With resigned faces and tired eyes, modestly cut frocks, and reserved body language, these women engage with neither the viewer nor one another, embodying a world of alienation. Alternately compassionate and voyeuristic, Lautrec’s brothel scenes are some of his most complex works. . . .

In 1899 Lautrec was institutionalized, owing to the advanced stages of alcoholism, which had plagued him much of his life. Determined to win his release, Lautrec made a series of crayon circus drawings from memory to prove the soundness of his mind. The fantastic and nightmarish quality of these drawings shows how the circus served as an ideal metaphor for the disordered Lautrec to articulate pictorially his inner struggles and traumas. Indeed, these poignant images secured his release from the clinic.

Upon returning to Montmartre, Lautrec resumed a life of artistic activity combined with heavy drinking and late nights. In the years that followed, Lautrec’s health deteriorated as his alcoholism progressed; he died in the arms of his mother on September 9, 1901. Although Lautrec lived only to the age of 36, he left behind a brilliant visual record of the spirit of Montmartre.