J.-K. Huysmans' A rebours (Against Nature)

| J.K. Huysmans was

the most visible writer in the Decadent Movement in France in the

last decades of the 19th century. We will be considering his

work in that capacity tomorrow, but the passage below provides an

example of the concern of elite writers with distinguishing

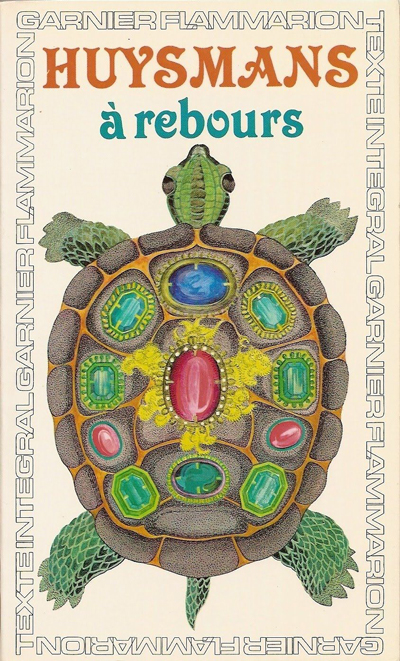

themselves from the masses. The central character in this novel is the duc des Esseintes, the last descendent of an aristocractic family, who withdraws from society and creates a bizarre environment at his chateau in which everything sets him apart from the "common" people of his time. In this passage he is deciding which jewels to encrust on the shell of his tortoise -- that will be clearer in the longer passage on tomorrow's website -- and he rejects certain gems because of their association with the "masses." |

The choice of the stones gave him pause; the diamond

had grown singularly hackneyed now that every business man wears one on his

little finger; Oriental emeralds and rubies are less degraded and dart fine, flashing lights, but

they are too reminiscent of those green and red eyes that shine as

head-lights on certain lines of Paris omnibuses; as for topazes, burnt or

raw, they are cheap stones, dear to the humble housewife who loves to lock

up a jewel-case or two in a glasscupboard; of another sort, the amethyst,

albeit the Church has given it something of a sacerdotal character, is yet a

stone spoilt by its frequent use to ornament the red ears and bulbous hands

of butchers’ wives who are fain at a modest cost to bedeck their persons

with genuine and heavy jewels. Alone among all these, the sapphire keeps its

fires inviolate, unharmed by the folly of tradesmen and money-grubbers. The

brilliance of its fire that sparkles from a cold, limpid background has to

some degree guaranteed against defilement its discreet and haughty nobility.

But unfortunately by artificial light its bright flames flash no longer; the

colour sinks back into itself and seems to go to sleep, only to wake and

sparkle again at daybreak.

emeralds and rubies are less degraded and dart fine, flashing lights, but

they are too reminiscent of those green and red eyes that shine as

head-lights on certain lines of Paris omnibuses; as for topazes, burnt or

raw, they are cheap stones, dear to the humble housewife who loves to lock

up a jewel-case or two in a glasscupboard; of another sort, the amethyst,

albeit the Church has given it something of a sacerdotal character, is yet a

stone spoilt by its frequent use to ornament the red ears and bulbous hands

of butchers’ wives who are fain at a modest cost to bedeck their persons

with genuine and heavy jewels. Alone among all these, the sapphire keeps its

fires inviolate, unharmed by the folly of tradesmen and money-grubbers. The

brilliance of its fire that sparkles from a cold, limpid background has to

some degree guaranteed against defilement its discreet and haughty nobility.

But unfortunately by artificial light its bright flames flash no longer; the

colour sinks back into itself and seems to go to sleep, only to wake and

sparkle again at daybreak.

No, not one of these stones satisfied Des Esseintes; besides, they were all too civilized, too familiar. He preferred other, more startling and uncommon, sorts. After fingering a number of these and letting them trickle through his hands, he finally picked out a series of stones, some real, some artificial, the combination of which should produce a harmony, at once fascinating and disconcerting.