Literary presentations of Male Homosexuality

From Robert Nye, “The Culture of the Sword: Manliness and Fencing in the Third Republic” from Masculinity and Male Codes of Honor in Modern France (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), pp. 119-121.

Of course, literary portrayals of homosexuality at the turn of the century were only part of the spectrum of literary representations that considered the effects social and economic change produced on sex roles and sexual identity. As several scholars have noted, the writers and painters of this era, men and women alike, were fond of themes that tested the male response to the new female assertiveness in public life and to the "eroticization" of bourgeois marriage. The binary term strong women/weak me -- and its sexual analogue, fatal women/impotent men -- was popular both with authors who feared the effects of female emancipation, and with those who supported it. As Annelise Mauge has written about these characterizations, "With the [anticipated] emancipation of women, something has been refused males which seemed so much constitutive of their identity that they felt themselves totally rejected as men."

As was the case in the medical literature, these themes were closely related, if not inseparable from literary explorations of homosexuality, implying in particular the notion that the appearance of new male and female types announced the eventual disappearance of the traditional sexual order. Although the domestic family-loving wife by no means vanished, the lesbian and the "androgyne" appeared alongside her, while the strong male, the "mari-pedagogue," and the oversexed male were joined by less

virile types. Marcel Prévost , Victor and Paul Margueritte, Adolphe Belot, Colette Yver, Catulle Mendes, and many other authors whose names have faded from memory peopled their novels and plays with the same sexually ambiguous characters as more famous authors: Emile Zola, loris Karl Huymans, Marcel Proust, André Gide, Rémy de Gourmont, Joséphin Péladan

, Pierre Louys, Rachilde, and Jean Lorrain.

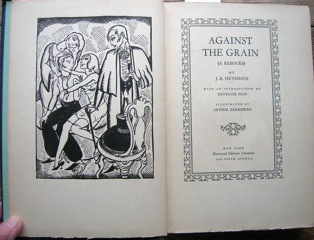

Despite the zeal that the authors of this era exhibited for representations of homosexuality and sexual perversion, openly sympathetic homosexual novels were rare indeed. More typical of the "decadent" novel was the assumption of a gravely ironic or a comic perspective on unusual couplings or peculiar desires. The ur-text for many of these novels was perhaps the most famous of them all: Joris-Karl Huysmans's A Rebours ("Against the Grain"), which appeared in 1884. Huysmans, whose explorations of the underworld of human perversion tipped him eventually into a mystical Catholicism, presented in the person of his hero, Des Esseintes, the perfect type of exhausted and degenerate aristocrat, a last anemic shoot from a once-vigorous warrior stock. Des Esseintes can arouse his feeble energies only by employing parapraxes or elaborate subterfuges that are, without actually taking the name, fetishes. Three episodes of recollection in chapter 9 chronicle his progressive sexual collapse in a style that is virtually interchangeable with the psychiatrist's case study.

Despite the zeal that the authors of this era exhibited for representations of homosexuality and sexual perversion, openly sympathetic homosexual novels were rare indeed. More typical of the "decadent" novel was the assumption of a gravely ironic or a comic perspective on unusual couplings or peculiar desires. The ur-text for many of these novels was perhaps the most famous of them all: Joris-Karl Huysmans's A Rebours ("Against the Grain"), which appeared in 1884. Huysmans, whose explorations of the underworld of human perversion tipped him eventually into a mystical Catholicism, presented in the person of his hero, Des Esseintes, the perfect type of exhausted and degenerate aristocrat, a last anemic shoot from a once-vigorous warrior stock. Des Esseintes can arouse his feeble energies only by employing parapraxes or elaborate subterfuges that are, without actually taking the name, fetishes. Three episodes of recollection in chapter 9 chronicle his progressive sexual collapse in a style that is virtually interchangeable with the psychiatrist's case study.

The first of these episodes involves the American acrobat Miss Urania, she of the "supple body, sinewy legs, muscles of steel, and arms of iron ." The fragile Des Esseintes imagines a kind of "change of sex" in which she would take the man's role in their relationship, because he was himself "becoming increasingly feminized." He is bitterly disappointed, however, because her sexual comportment is in fact conventionally coy and passive, aggravating his already "premature impotence." His second mistress was a cafe-concert ventriloquist, a dark and boyish woman who captivated Des Esseintes by her consummate ability to project exotic literary dialogue into statues of the Chimaera and the Sphinx. Inevitably, however , "his [sexual] weakness became more pronounced; the effervescence of his brain could no longer melt his frozen body: the nerves no longer obeyed his will; the mad passions of old men overtook him. Feeling himself grow more and more sexually indecisive, he had recourse to the most effective stimulant of old voluptuaries, fear":

While he held her clasped in his arms, a husky voice burst out from behind the door: "Let me in, I know you have a lover with you, just wait, you trollope." Suddenly, like the libertines excited by the terror of being taken en flagrant delit outdoors .. . , he would temporarily recover his powers and throw himself upon the ventriloquist, who continued to hurl her shouts from beyond the door. . . . '

Rejected finally by this woman, who preferred a man with "less complicated requirements and a sturdier back ," Des Esseintes embarked on a homosexual affair with an effeminate, young Parisian gavroche, the last stage, so to speak , of his sexual decline: "never had he experienced a more alluring and imperious liaison ; never had he tasted such perils nor felt himself so painfully fulfilled." 123

Characterizations such as this of homosexuals and of homosexual love reiterated the standard medical portrait of the invert [i.e. homosexual] as an unmanned degenerate, condemned to a kind of love in keeping with his reduced biological condition . Though, as we have seen, it was possible elsewhere to write and speak about a different, more masculine kind of homosexual, in France the concept of the effeminate invert invariably subverted all other varieties. When Andre Raffalovitch, a francophone propagandist for homosexual rights, tried to make a case in French medical journals for the existence of a type of homosexual who was manly, married, and head of a household , he did so while heaping abuse on "effeminate" inverts, arguing that their moral worth was in inverse relation to their degree of effeminacy.

Emile Zola, Dreyfusard [i.e. a defender of Alfred Dreyfus -- see Day 9] and noble crusader for unpopular causes, pleaded the cause of inverts in his preface to Georges Saint-Paul's book on sexual perversions. He observed that one does not condemn a hunchback for having been born that way, so why scorn a man for acting like a woman when he has been born half woman? But Zola follows his halfhearted plea for understanding with a piece of bald familialist ]i.e. in favor of traditional heterosexual marriage] propaganda: "And in the end everything which touches on sex touches social life itself. An invert is a disorganizer of the family, of the nation, of humanity. Man and woman exist to make children, and they will kill life itself on the day they decide to make no more of them."