French Attitudes Towards Male Homosexuality

From Robert Nye, “The Culture of the Sword: Manliness and Fencing in the Third Republic” from Masculinity and Male Codes of Honor in Modern France (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), pp.108-110.

In view of the pioneering role played by French doctors in the movement toward a more humane treatment of the insane in the nineteenth century, one might have

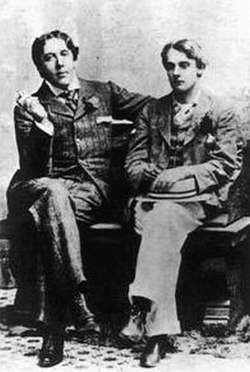

Oscar Wilde and Alfred Douglas (1893) The differences between English (and American) attitudes towards homosexuality and those in France was made clear by the case of Oscar Wilde. In the 1890s Wilde was probably the most popular writer in Britain, but, when the father of Alfred Douglas discovered that his son was having an affair with Wilde, he has charges filed against the author. After a highly publicized trial Wilde was sentenced to two years hard labor for having committed homosexual acts. He emerged from prison and found that the fashionable London houses that he had frequented were now closed to him. Crushed by the almost universal social rejection, he moved to Paris, where he lived in poverty until his death in 1900. His body still rests in Pere Lachaise cemetery.

|

reasonably assumed they would move in a similar direction. But they did not. French doctors were conspicuous by their absence from Hirschfeld's international Scientific Humanitarian Committee. There was virtually no medically-led homosexual rights agitation in France until after 1945, and then only of a tentative kind.

Part of the reason for this inactivity was the very "liberality"of the Napoleonic Code on sexual crimes. The code punished only forcible rape, child molestation, and "outrage" to public decency; it laid down no penalty for sodomy or homosexual acts, indeed did not mention them by these or any other name. This silence was not one inspired by horror. In matters of sexual comportment, the code followed the same noninterventionist libertarianism that had informed the civil rights agenda of the Declaration of the Rights of Man: "All that is not expressly forbidden by the law is permitted." More out of a consistent vision of the law than for any other reason, no major statutory emendations were made respecting homosexual behavior until a relatively mild law of 1941 under the Vichy regime. What rights might discontented homosexuals or their medical allies claim in an atmosphere of such legal forbearance?

This is not to say that the authorities were unable to use the law against homosexual practices when they wished. Article #330 on "public outrage" was used throughout the nineteenth century against homosexual prostitution. This part of the code replaced the sodomy law that that been used as the legal pretext for arrest and conviction in the Old Regime. Article #331 on child molestation might well have been designed by the framers of the code to counteract pederasty, a practice that was regarded in law and in popular culture as qualitatively distinct from sodomy at the turn of the nineteenth century. Indeed, tolerance for this practice lessened in the course of the century, exemplified by the advance of the age of minority in this crime from eleven to thirteen years old in 1863.

As a general rule, however, the state seldom used the criminal law as its entering wedge into the domain of private sexuality. Unlike the regulation of sexuality in the Anglo-Saxon legal tradition, French law respected the distinction between private and public sexual behavior, for the most part confining its efforts at law enforcement to the latter domain. This had also been so in the Old Regime, when the brigade des moeurs [standards brigade] conducted its sweeps through the public parks and other sites popular for homosexual encounters. From what we can tell, the homosexual vice squad that was formed under the Second Empire by the police prefect F. Carlier aggressively pursued its mandate to round up homosexual prostitutes and pederasts, but did not interfere with acts unlikely to be the occasion for chance public witness.

The legal and police discrimination between public and private was mirrored , perhaps shaped, in practice by a social distinction between rich and poor, between those who had the time and means to conduct their erotic relationships in private, and those whose sexual lives were more exposed to view. Thus, lower-class homosexuals were arrested routinely in vice squad raids on public urinals, but by the end of the century there is considerable evidence that upper-class homosexuals and lesbians benefited sufficiently from their relative legal invulnerability to attain a kind of tolerated status in elite life. It is nonetheless unlikely, as Eugen Weber has implied, that homosexuality and other "fashionable perversions" were simply exotic identities casually assumed by bored or esthetically inclined poseurs for their shock value. An identity lightly worn is not necessarily one lightly chosen.

The multifaceted social and cultural life of fin de siecle Paris permitted a greater range of personal expression than had been possible at any earlier time in the capital or in contemporary provincial life, but there were definite limits on the forms these expressions might take, and these limits were not enforced by the law, but by opinion. There is reason to believe that homosexuals themselves took careful note of this fact and conducted themselves accordingly. For the discreet homosexual male, there was little need to fear direct police intervention in his private life; he had much more to fear, however, from the judgments of his fellow citizens about the quality of his masculinity.

It is my argument here and in later chapters that in this era assessments about a man's masculinity took on an unusual importance in social life. At least for middle and upper-class men, being anatomically "of the male sex" was necessary, but was not in itself sufficient to satisfy the ideals of masculinity articulated routinely in public discourse. . .