Ann-Louise Shapiro, Housing the Poor of Paris, 1850-1902

DETERIORATING HOUSING CONDITIONS

As rent increases produced evictions, workers did try to stay within their arrondissements when looking for new lodgings; nevertheless, cheaper prices and lesser densities inevitably drew the working class to the outlying  districts, especially to arrondissements XIII, XIX, and XX, where conditions were initially less crowded, but no less grim. Between 1876 and

1886 the number of people per lodging increased from 2.75 to 3.01 in the thirteenth arrondissement; from 2.86 to 3.08 in the nineteenth; and from

2.74 to 2.99 in the twentieth. In contrast, the fifth and sixth arrondissements, in the city center, witnessed a decline in the numbers of people per lodging: 2.99 to 2.97 and 3.14 to 2.88, respectively. Du Mesnil observed that "although recently there has been a tendency for the migration of workers to the suburbs, the effects have not been significant or salutary... . The same exploitation has occurred in the suburban territories ... the new housing built for workers often reproduces exactly the nuisances which with great difficulty were finally suppressed in older housing." Many of the new houses in the peripheral arrondissements were plaster and tarpaper shanties hastily erected in the open fields and hence immune from the minimal regulations which set standards for housing aligning public thoroughfares (decree of March 26, 1852). . . .

districts, especially to arrondissements XIII, XIX, and XX, where conditions were initially less crowded, but no less grim. Between 1876 and

1886 the number of people per lodging increased from 2.75 to 3.01 in the thirteenth arrondissement; from 2.86 to 3.08 in the nineteenth; and from

2.74 to 2.99 in the twentieth. In contrast, the fifth and sixth arrondissements, in the city center, witnessed a decline in the numbers of people per lodging: 2.99 to 2.97 and 3.14 to 2.88, respectively. Du Mesnil observed that "although recently there has been a tendency for the migration of workers to the suburbs, the effects have not been significant or salutary... . The same exploitation has occurred in the suburban territories ... the new housing built for workers often reproduces exactly the nuisances which with great difficulty were finally suppressed in older housing." Many of the new houses in the peripheral arrondissements were plaster and tarpaper shanties hastily erected in the open fields and hence immune from the minimal regulations which set standards for housing aligning public thoroughfares (decree of March 26, 1852). . . .

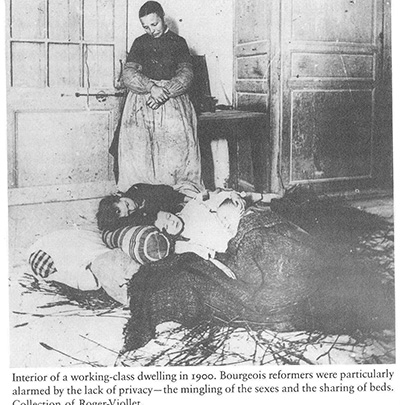

Investigators produced accounts of working-class districts on the periphery of the city which were truly horrific. Du Mesnil described the terrains vagues on which clusters of housing were erected as veritable sewers. Private roadways without any form of drainage turned streets into foul swamps in which the ruts and potholes were filled with decaying matter. Frequently liquid and solid wastes from clogged cesspits seeped into the first-floor living quarters of adjoining properties, while privies without covers overflowed into courtyards, and open gutters intersected walkways. "One can say," claimed Du Mesnil, "that here one breathes death."53 The Pelloutier brothers echoed these findings. They wrote: "To enter into the houses is even worse. Dark, sticky with humidity and dirt which forms a paste, the corridors seem to be entries into underground passages or even into cesspits. The gas of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide expands as above a night-soil dump... . One lacks courage to climb the stairs and hastens to get out of the corridor." Du Mesnil found, further, that in many cases two-thirds of the inhabitants did not have beds, five or six people might share the same bed, and others rented their beds during the daytime hours. During a cold winter, stair railings, doors, and windows had been broken up for firewood, and as rooms became uninhabitable, they increasingly became the repository for dirt and garbage. Rarely was there any water at all, either for washing or for cleaning. Fifteen to twenty people usually shared a privy, although there were examples of as many as fifty or sixty people using the same facility. In one such hovel in the thirteenth arrondissement the rent was Fr 3.75 per week. . . .

Thus, the inequality of conditions, both in life and in death, between the ten central arrondissements and the ten peripheral arrondissements which Jules Simon had lamented in 1869 became more pronounced during the Third Republic. High mortality in the poorest districts, underlined especially by the persistence of tuberculosis, identified working-class housing as the breeding ground of infection and disease. Not only were the garbage heaps and wastes surrounding workers' housing seen as a serious public hazard, but contemporaries had come to understand the very walls, ceilings, furniture, and clothing of the worker as presenting a danger which was largely immune to remedial public works policies. The unhealthful dwellings commission could attempt stricter enforcement of sanitary standards, but under contemporary conditions, increased rigor largely meant a policy of shoveling out the poor. Du Mesnil observed that the only remedy for buildings in a state of total decay and insalubrity was to tear them down. But demolition had to be countered with new construction. The situation was comparable, according to Du Mesnil, to the aftermath of a flood, fire, or famine -- a crisis which called for immediate, positive action. The mechanism of the free market did not supply the remedy. Rising land values and the prospect of substantial profits drew contractors to the construction of bourgeois and luxury dwellings and increasingly away from lodgings for the working class. While construction lagged, the population continued to increase by significant numbers through the end of the century. It remained for philanthropists, reformers, and politicians to attempt to manipulate the market so as to make the construction of working-class housing an attractive proposition for entrepreneurs who clearly believed that their best interests lay elsewhere.

Thus, the inequality of conditions, both in life and in death, between the ten central arrondissements and the ten peripheral arrondissements which Jules Simon had lamented in 1869 became more pronounced during the Third Republic. High mortality in the poorest districts, underlined especially by the persistence of tuberculosis, identified working-class housing as the breeding ground of infection and disease. Not only were the garbage heaps and wastes surrounding workers' housing seen as a serious public hazard, but contemporaries had come to understand the very walls, ceilings, furniture, and clothing of the worker as presenting a danger which was largely immune to remedial public works policies. The unhealthful dwellings commission could attempt stricter enforcement of sanitary standards, but under contemporary conditions, increased rigor largely meant a policy of shoveling out the poor. Du Mesnil observed that the only remedy for buildings in a state of total decay and insalubrity was to tear them down. But demolition had to be countered with new construction. The situation was comparable, according to Du Mesnil, to the aftermath of a flood, fire, or famine -- a crisis which called for immediate, positive action. The mechanism of the free market did not supply the remedy. Rising land values and the prospect of substantial profits drew contractors to the construction of bourgeois and luxury dwellings and increasingly away from lodgings for the working class. While construction lagged, the population continued to increase by significant numbers through the end of the century. It remained for philanthropists, reformers, and politicians to attempt to manipulate the market so as to make the construction of working-class housing an attractive proposition for entrepreneurs who clearly believed that their best interests lay elsewhere.