Valerie Steele, Paris Fashion: A Cultural History

The Pursuit of Pleasure

In other capitals, the stranger has to go in quest of amusement. In Paris, he cannot stir a step without coming in contact with the clashing cymbals of the votaries of pleasure.

Thomas Forrester, Pans and Its Environs, 1859

The pursuit of pleasure was an important key to fashion behavior. According to the guidebook The Plaisirs de Paris (1867) you must "deprovincialize yourself before you emparisienner." [become Parisian]Read the fashion journals and patronize the tailors used by the nobility and the "gentlemen of the club and turf"- tailors such as Humann-Kerkoff, Renard, Dusantoy, and Po adere. Dehon makes good hats, Sakowski boots, and Jouvin gloves. They will all dress you in le dernier chic. "

"Go ahead!" the author urged (in English), enjoy the "high life" of Paris and by high life, I mean the demi-monde." [courtesans] If you want a guide to museums, look elsewhere, because this book is devoted to theatres, balls, and horse races. Just remember, you will. only have success with the loose ladies of Paris when you are properly dressed. If you look like a provincial, they will just laugh at you.1

Of course, the foreigner and the provincial, like all outsiders, tended to be excluded from the private life of Paris. Important social arenas, such as the salon and the "white ball" were for fashion insiders only. Mere tourists would not see the debutante at her first ball, wearing a symbolic white dress: "She has worn this chaste and poetic white on the day of her first communion; and she will wear it when she comes to the foot of the altar, to unite her life with that of the man she marries. This evening, it seems to be a sort of uniform . . . the color of hope . . . [and] innocence."2 Fortunately, most tourists were having too much fun in the public fashion arenas of the big city, to regret these private performances.

The Theatre of Experience

"The success of plays is certainly not purely literary," declared the Vicomtesse Lesse de Renneville, a well-known fashion reporter for the Gazette Rose:

In most cases the theatre can be certain of big crowds when sumptuous dresses can be seen on stage. ... Hardly has the rumour gone round that in a certain play many new toilettes will be shown, than a considerable part of the population is in a frenzy of excitement--dressmakers, modistes, makers of lingerie and designers.

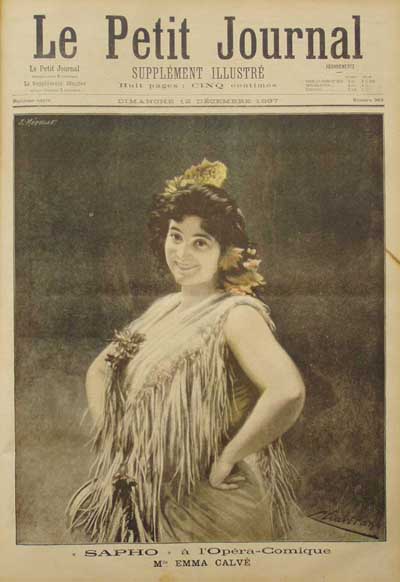

![]() Actresses were among the most important "arbiters of elegance." Not only were their stage costumes described and illustrated in the fashion press, but they themselves were interviewed about their fashion preferences. It is said of certain actresses that: "If they were entrusted with Racine or Corneille [masters of classical French drama] they prefer Paquin or Doucet." Madame Rejané, for example, favored the couturier Jacques Doucetm while Madame Lavallière chose Paquin. Elonora Duse collaborated closely with Jean Philippe Worth; once she sent him a telegram, complaining. "When you do not help me the magic leaves my roles." Sarah Bernhardt quarreled with Worth, when she refused to use only his dresses on stage.

Actresses were among the most important "arbiters of elegance." Not only were their stage costumes described and illustrated in the fashion press, but they themselves were interviewed about their fashion preferences. It is said of certain actresses that: "If they were entrusted with Racine or Corneille [masters of classical French drama] they prefer Paquin or Doucet." Madame Rejané, for example, favored the couturier Jacques Doucetm while Madame Lavallière chose Paquin. Elonora Duse collaborated closely with Jean Philippe Worth; once she sent him a telegram, complaining. "When you do not help me the magic leaves my roles." Sarah Bernhardt quarreled with Worth, when she refused to use only his dresses on stage.

But not only was there a culture of stage costume, the audience itself was on display. As one of the most important forms of entertainment for people of all classes and nations, the theater was featured as the setting of innumerable novels, paintings, and fashion plates. Here, too, the symbolic relationships between fashion performers and fashion spectators were especially clearly expressed.

People did not only go to the theatre to see the performances on stage. It was at least as much a social ritual, and there were fairly strict rules concerning who could sit where and what was the appropriate mode of dress to be worn. On the other hand, in the days before movies, people of all but the poorest classes attended the theatre, and there existed a much wider range of theatres, many of them distinctly popular. The theatres of the boulevards were low on the social hierarchy, and the clothing worn to them did not at all correspond to that depicted in fashion plates. There was also considerable clothing variation within any one theatre from court dress to workers' blouses -- depending on whether the spectator was in a private box or the orchestra pit.