Rosalind Williams, Dream Worlds

The Experience of Consuming

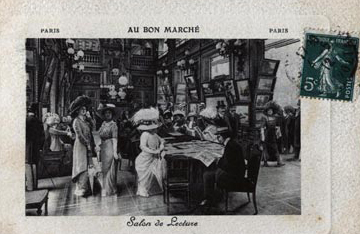

Exoticism in Department Stores-One obvious confirmation of this lesson was the emergence of department stores (in French grands magasins, "big" or "great"  stores) in Paris. The emergence of these stores in late nineteenth century France depended on the same growth of prosperity and transformation of merchandising techniques that lay behind the international expositions. Talmeyr was on the mark when he observed that the Indian exhibit at the Trocadero reminded him of an Oriental Louvre or Bon Marche. The Bon Marche was the first department store, opening in Paris in 1852, the year after the Crystal Palace exposition, and the Louvre appeared just three years later. The objective advantages of somewhat lower prices and larger selection which these stores offered over traditional retail outlets were not the only reasons for their success. Even more significant factors were their practices of marking each item with a fixed price and of encouraging customers to inspect merchandise even if they did not make a purchase. Until then very different customs had prevailed in retail establishments. Prices had generally been subject to negotiation, an d the buyer, once haggling began, was more or less obligated to buy.

stores) in Paris. The emergence of these stores in late nineteenth century France depended on the same growth of prosperity and transformation of merchandising techniques that lay behind the international expositions. Talmeyr was on the mark when he observed that the Indian exhibit at the Trocadero reminded him of an Oriental Louvre or Bon Marche. The Bon Marche was the first department store, opening in Paris in 1852, the year after the Crystal Palace exposition, and the Louvre appeared just three years later. The objective advantages of somewhat lower prices and larger selection which these stores offered over traditional retail outlets were not the only reasons for their success. Even more significant factors were their practices of marking each item with a fixed price and of encouraging customers to inspect merchandise even if they did not make a purchase. Until then very different customs had prevailed in retail establishments. Prices had generally been subject to negotiation, an d the buyer, once haggling began, was more or less obligated to buy.

The department store introduced an entirely new set of social interactions to shopping. In exchange for the freedom to browse, meaning the liberty to indulge in dreams without being obligated to buy in fact, the buyer gave up the freedom to participate actively in establishing prices and instead had to accept the price set by the seller. Active verbal interchange between customer and retailer was replaced by the passive, mute response of consumer to things- a striking example of how "the civilizing process" tames aggressions and feelings toward people while encouraging desires and feelings directed toward things.

Department stores were organized to inflame these material desires and feelings. Even if the consumer was free not to buy at that time, techniques of merchandising pushed him to want to buy sometime. As environments of mass consumption, department stores were, and still are, places where consumers are an audience to be entertained by commodities, where selling is mingled with amusement, where arousal of free-floating desire is as important as immediate purchase of particular items. Other examples of such environments are expositions, trade fairs, amusement parks, and (to cite more contemporary examples) shopping malls and large new airports or even subway stations. The numbed hypnosis induced by these places is a form of sociability as typical of modern mass consumption as the sociability of the salon was typical of prerevolutionary upper-class consumption.

Department stores were organized to inflame these material desires and feelings. Even if the consumer was free not to buy at that time, techniques of merchandising pushed him to want to buy sometime. As environments of mass consumption, department stores were, and still are, places where consumers are an audience to be entertained by commodities, where selling is mingled with amusement, where arousal of free-floating desire is as important as immediate purchase of particular items. Other examples of such environments are expositions, trade fairs, amusement parks, and (to cite more contemporary examples) shopping malls and large new airports or even subway stations. The numbed hypnosis induced by these places is a form of sociability as typical of modern mass consumption as the sociability of the salon was typical of prerevolutionary upper-class consumption.

The new social psychology created by environments of mass consumption is a major theme of Au Bonheur des Dames . In creating his fictional store Zola did not rely on imagination alone; he filled research notebooks with observations of contemporary department stores before writing his novel. Zola's fictional creation in turn influenced the design of actual stores. He invited his friend, architect Frantz Jourdain , to draw an imaginary plan for Au Bonheur des Dames, and not many years later Jourdain began to collaborate on an ambitious renovation and building program for La Samaritaine, a large department store in the heart of Paris. By 1907, when most of the program was completed, the store closely resembled Zola's descriptions of Au Bonheur des Dames. Ernest Cognacq, founder of La Samaritaine, was an energetic entrepreneur who probably served as a model for Octave Mouret, the imaginative and innovative owner of Au Bonheur des Dames.

In loving detail Zola describes how Mouret employed exotic decor to encourage shoppers to buy his wares. One section of the novel portrays the reaction of the public to a rug exhibit on the day of a big sale:

[TJhe vestibule [was] changed into an Oriental salon. From the doorway it was a marvel, a surprise that ravished them all. Mouret . . . had just bought in the Near East, in excellent condition, a collection of old and new carpets, those rare carpets which till then only specialty merchants had sold at very high prices, and he was going to flood the market, he gave them away at cut rates, extracting from them a splendid decor which would attract to the store the most elegant clientele. From the middle of Place Gaillon could be seen this Oriental salon made only of rugs and curtains. From the ceiling were suspended rugs from Smyrna with complicated patterns that stood out from the red background. Then, from th e four sides, curtains were hung: curtains of Karamanie and Syria, zebra-striped in green, yellow, and vermilion; curtains from Diarbekir, more common, rough to the touch, like shepherds' tunics; and still more rugs, which could serve as wall hangings, strange flowerings of peonies and palms, fantasy released in a garden of dreams.8

Customers kept drifting into the store, attracted by this decor so similar to that of the Trocadero, "the decor of a harem," in Zola's words. By afternoon the building was overflowing with a crush of excited, eager shoppers. At the end of the day some of them met in the Oriental salon so they could depart together; they were so en chanted by the rug display that they could talk of nothing else:

They were leaving, but it was in the midst of a babbling crisis of admiration. Mme. Guibal herself was ecstatic:

"Oh! delicious! ... "

"Isn't it just like a harem? And not expensive!"

"The Smyrnan ones, ah! the Smyrnan ones' What tones, what finesse!"

"And this one from Kurdistan, look! a Delacroix!" It was the most profitable day in the history of Au Bonheur des Dames.

The department store dominates the novel. The virtuous but pallid Denise, Octave Mouret, the crudely drawn entrepreneur who tries unsuccessfully to seduce Denise, and the female shoppers whom Mouret does seduce commercially, are all subordinate to the store, which seems to overwhelm them and control their destinies. It does this through means essentially the same as those employed at the Trocadero exhibits. The counters of the department store present a disconnected assortment of "exhibits," a sort of "universe in a garden" of merchandise. The sheer variety, the assault of dissociated stimuli, is one cause of the numbed fascination of the customers. Furthermore, the decor of the department store repeats the stylistic themes characteristic of the Trocadero: syncretism, anachronism, illogicality, flamboyance, childishness. In both cases the decor represents an attempt to express visions of distant places in concrete terms. It is a style which may without undue flippancy be called the chaotic-exotic. But within one exhibit not chaos but repetition is often employed to numb the spectator even further. When rugs are placed on the ceiling, walls, and floor of the vestibule, when the same item is repeated over and over with minor variations-just as the Andalusian exhibit at the Trocadero had camels here, camels there, camels everywhere-the sheer accumulation becomes awesome in a way that no single item could be. The same effect is achieved when Mouret fills an entire hall with an ocean of umbrellas, top to bottom, along columns and balustrades and staircases; the umbrellas shed their banality and instead become "large Venetian lanterns, illuminated for some colossal festival," an achievement that makes one shopper exclaim, "It's a fairyland!"

Mouret's most stunning coup, however, is his creation of his own exposition, an "exposition of white," to celebrate the opening of a new building. The description of this event forms the final chapter of Au Bonheur des Dames, where it becomes a climactic hymn of praise to modern commerce. Mouret constructs a dreamland architecture of "white columns ... white pyramids ... white castles" made from white handkerchiefs, "a whole city of white bricks ... standing out in a mirage against an Oriental sky, heated to whiteness."11 In this display, exotic fantasies merge with oceanic ones, and dreams of distant places fade into dreams of bathing in passive bliss, surrounded on all sides by comfort, a fantasy of a return to the womb, which has become a womb of merchandise.

The Gallery of Paintings at Au Bon Marché in 1880