H. Hazel Hahn, Scenes of Parisian Modernity: Culture and Consumption in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Palgrave, 2009), pp. 139, 143, 148,

Spectacle on the Boulevards

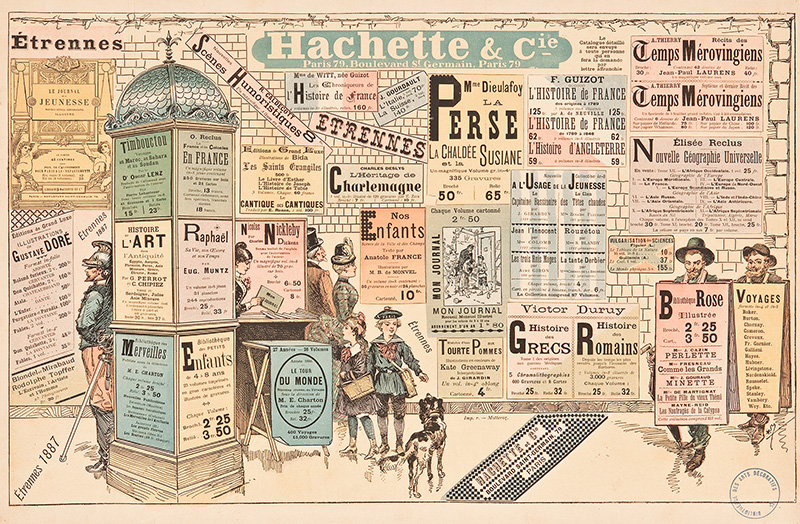

The proliferation of spectacular advertising in the street, as well as the vast output of illustrated posters, led foreign experts to

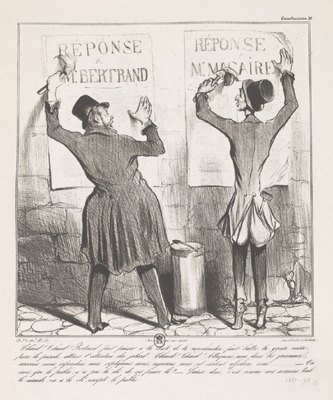

"Hot Stuff! Hot Stuff! We "must bolster our sales, Bertrand, must beat the big drum…attack ourselves in the papers, write, reply to ourselves, retort, insult ourselves and above all advertise ourselves." Daumier, 1837 |

contrast French advertising, emphasizing entertainment and theappearance of the media that blended into the decor of the street, with the Anglo-American variety, emphasizing the strategy of "obsession " through sheer volume and repetition. Octave Uzanne likewise remarked in 1904 that whereas in England and the United States one could immediately sense "the hallucination" of the odious and omnipresent advertising, a study in French advertising was "sure to be tremendously picturesque and amusing, as advertising has taken on all forms and dissimulates itself under the most ingenious disguises." The French specialized in "fantastic and amusing advertising," for which Paris "had its unforgettable and original types." For example four dandies in overcoats shouted slowly in unison, "This evening, at 'Dementes-Bergeres' [the Squabbling Shepherdesses] at eight o'clock, a grand performance." Ten men, promenading on the Grands Boulevards "attracted attention through their rather forced elegance." At the terrace of each cafe, they took off their hats and bowed deeply, showing ten shaven heads on which were collectively written an advertising slogan for a liqueur. A 1902 caricature depicted the Boulevards as overrun by advertising including people all advertising something. Men and women in costumes created "a vision of carnival." On the Boulevards men with half-blond and half-black hair advertised wigs. Young women wearing "immaculate shirts" advertised a wash-house, and men in black costume carried pocket lanterns. Four young women paraded arm in arm on the Boulevards announcing attractions as they were besieged, followed and photographed. . .

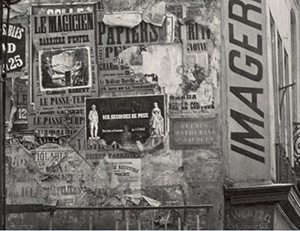

Parisian Wall, 1860 |

Parisian cityscape changed dramatically during the Second Empire and the ThirdRepublic, not only through large-scale urban planning but also through a surge of commercial posters -- including large illustrated lithographed posters from the 70s -- signs, murals, and street furnishings in the street. The French advertising industry was established through myriad practices and establishments that preceded the urban transformation under Baron Haussmann but whose effects were at their height from the 1880s, after the passing of the landmark 1881 press. . .

The display of advertisements was a part of the organization of urban space, regulation of traffic and aesthetic rationalization orchestrated by Haussmann, which included the extensive building of a sewage system and the reorganization of the catacombs. However, the Grand Boulevards remained a magnet for advertising and publicity. An 1849 project proposed to set up gas candelabras on the Boulevard s that would serve as advertising media, and the thoroughfare was crowded from the 1860s with a variety of advertising media. At the same time traditional itinerant hawkers and entertainers were increasingly replaced by modern commerce.

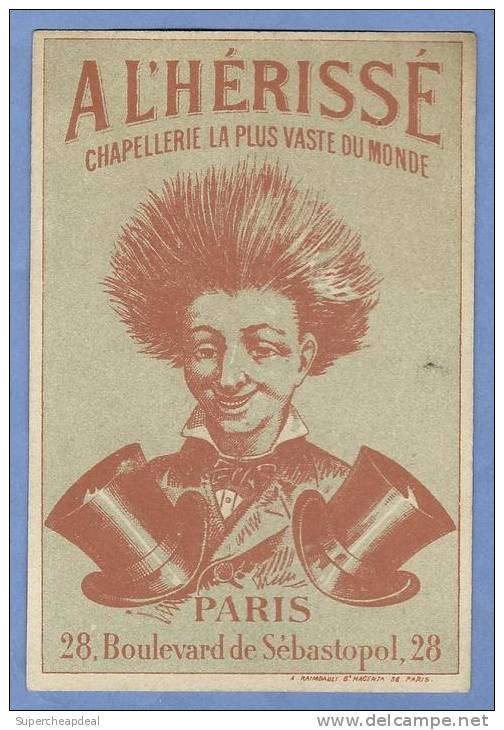

Issues of taste and monumental aesthetics also came to the fore. By the late 1850s "vast sections of walls, even chimneys" were  painted with advertisements. Many mural advertisements looked like giant shop signs, listing the inventory of shops. Others depicted symbols. Gigantic murals, such as A l'Oeil 's [at the eye] mysterious pupil, Le Bon-Diable's [the good devil] green devil, L'Herisse's [bad hair] head with a halo of caps, and Le Piano Quatuor's [the piano quartet] man with "hideous long fingers and pointed nails stretching over the strings of four violin s" formed part of the urban picturesque. As the embellishment of Paris progressed, such commercial images came under fire, partly because the building of

painted with advertisements. Many mural advertisements looked like giant shop signs, listing the inventory of shops. Others depicted symbols. Gigantic murals, such as A l'Oeil 's [at the eye] mysterious pupil, Le Bon-Diable's [the good devil] green devil, L'Herisse's [bad hair] head with a halo of caps, and Le Piano Quatuor's [the piano quartet] man with "hideous long fingers and pointed nails stretching over the strings of four violin s" formed part of the urban picturesque. As the embellishment of Paris progressed, such commercial images came under fire, partly because the building of

numerous new thoroughfares creating new perspectives made the signs much more visible. Critics focused on the issues of taste and monumental aesthetics. One consequence of the drastic increase inelegant retail spaces and newly opened-up vistas was a campaign to rid of advertisements deemed inappropriate for the newly embellished surroundings. Charles Garnier , the architect of the Opera, criticized commercial murals as "the baroque, the bizarre, bad taste and impudence," spoiling the effects of alignment and perspective, and threatening "the love of the good and the sentiment of the beautiful." Likewise Eugene Viollet-Le-Duc, architect and theorist at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, wrote of his eyes being "violently drawn by an enormous golden plaque, 'TEETH AT FIVE FRANCS .' " He then saw a gargantuan wardrobe: "twenty-meter tall frock coats" and "gigantic slippers" that were "more visible than monuments." The unexpected contrast of monuments and images of enlarged commodities gave some observers a jarring sensation that might be termed "proto-Surrealist." In addition, although advertising carriages had been suppressed since 1847, countless delivery vehicles displayed shop signs and images.

A Parody of Street Advertising in Paris