The City

and its Poor

Edward R. Udovic, (1993)

""What About the Poor?" Nineteenth-Century Paris and the Revival of

Vincentian Charity," Vincentian

Heritage Journal: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1

, Article 5.

Available at:

https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol14/iss1/5

| In

this passage Udovic, a Catholic priest, is laying the ground

work for an article about the reaction of his church’s response

to poverty in 19th

century France. To refer to the poor, he uses the French term

Les Miserables, meaning “the miserable or wretched ones”

borrowed form the title of a novel by Victor Hugo. |

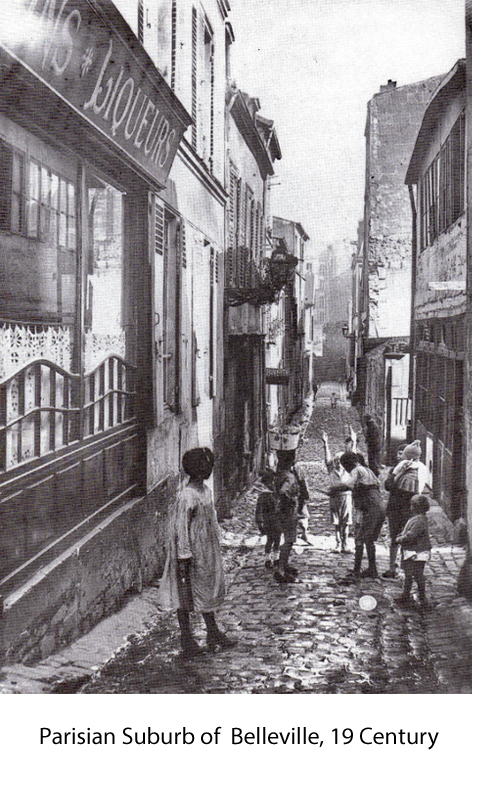

The Paris of Victor Hugo's lifetime

(1802-85), was the Paris of Napoleon I, the Paris of the Bourbon

Restoration of Louis XVIII, and of Charles X, the Paris of the bourgeois

July Monarchy of Louis Philippe, the Paris of the short-lived Second

Republic, the Paris of the Second Empire of Napoleon III and of Baron

Hausmann, the Paris of the Revolutions of 1830, of 1848, of the Prussian

siege of 1870, of the bloody Commune of 1871. It was also the

burgeoning, impoverished, often violent Paris of the Industrial

Revolution.

During

these years and in this Paris, Les

miserables were by definition the great

masses of the urban poor who between 1801 and 1850 doubled the

population of a city which was totally unprepared, unwilling, and

unable, to provide for them. La misere,

by the same contemporary understanding,

was the word which came to express their collective experiences of

marginalization, oppression, poverty, and suffering. ('Louis Chevalier,

Laboring Classes and Dangerous

Classes in Paris during the First Half of

the Nineteenth Century,

trans. Frank Jellinek (New York: 1973),

181-84.)

This same Paris by the consensus of

all contemporary statistical measures, and by the consensus of all

contemporary reports and accounts, was acknowledged to be a city that

had fallen dangerously ill. The pathologies which afflicted the city of

Paris were the pathologies which afflicted its poor. Although there was

disagreement as to the diagnosis of the exact nature of this illness

everyone recognized its symptoms and their fatal consequences.

To be

born, to live, and to die among those who were considered by French

society, and who indeed considered themselves as being

les

miserable, meant synonymously not only

that you were poor, not only that you were suffering, not only that you

were an exploited member of the working classes, but also that it was

assumed you were a member, either potentially or in actuality, of what

were then commonly referred to as the "criminal" classes. This meant

that you were considered to be a member, potentially or actually, of

what was described with a palpable sense of dread and fear by "polite"

bourgeois society as, the "barbarians and savages" of

les classes dangereuses,

the dangerous classes.

The Costs to the Poor.

The poor of Paris -- its men and women, its elderly, its adolescents, its children, and its infants -- all paid the comprehensive human costs of this industrialized and capitalistic "urban pathology." They paid this cost in the following measurable and measured ways: in hunger, in sickness, in malnutrition, in the lack of education, in begging, in homelessness, in unemployment, in the exploited employment of women, in abusive child labor, in the general mortality of the great cholera epidemics of 1832 and 1849, in infant mortality, in infanticide, in infant abandonment, in orphans, in suicide, in prostitution, in insanity, in violence, in endemic crime, in class warfare, in riots, civil unrest, and in revolution. In short, the poor paid fully in every conceivable way.

It has been estimated

that in this era Les miserables

always comprised at least one quarter of the

constantly increasing population of Paris, and that in times of economic

crisis the number increased bringing "hunger, sickness and death to

nearly one half of the Paris population."

As

Louis Chevalier has pointed out, these statistics "project a vast

structural poverty, a fundamental poverty ... a monstrous and permanent

poverty ... onto the background of the history of Paris."