Rachel G. Fuchs, Poor and Pregnant in Paris: Strategies for Survival in the Nineteenth Century, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1992, pp. 11-12.

Ernestine

Pallet's unwed mother died soon after giving birth to her in 1862 at the

public hospital , l'Hotel- Dieu.

Ernestine was released

to her aunt who soon abandoned her at the public foundling home, the

Hospice des Enfants Assistes. Foundling home authorities sent Ernestine

to a wetnurse and foster family who worked as farmers in Burgundy. When

Ernestine was twelve , her aunt reclaimed her and placed her as an

apprentice metal polisher. In 1878, at the age of sixteen, while still

living with her aunt and working as a metal polisher, Ernestine met

Eugene Legault, a twenty-two-year-old whom many accused of being lazy

and brutal. When drunk, he chased Ernestine with a knife. Ernestine

quarreled with her aunt who vehemently opposed the liaison, so she moved

into a cheap furnished room in the eleventh arrondissement in the

Belleville section of Paris. She soon became pregnant , and in November

1879, when she sought admission to nearby l'Hopital Saint-Louis, the

admissions officers brought her to a nearby public-welfare midwife where

she gave birth to a baby boy. Pallet was just seventeen at the time.

Dieu.

Ernestine was released

to her aunt who soon abandoned her at the public foundling home, the

Hospice des Enfants Assistes. Foundling home authorities sent Ernestine

to a wetnurse and foster family who worked as farmers in Burgundy. When

Ernestine was twelve , her aunt reclaimed her and placed her as an

apprentice metal polisher. In 1878, at the age of sixteen, while still

living with her aunt and working as a metal polisher, Ernestine met

Eugene Legault, a twenty-two-year-old whom many accused of being lazy

and brutal. When drunk, he chased Ernestine with a knife. Ernestine

quarreled with her aunt who vehemently opposed the liaison, so she moved

into a cheap furnished room in the eleventh arrondissement in the

Belleville section of Paris. She soon became pregnant , and in November

1879, when she sought admission to nearby l'Hopital Saint-Louis, the

admissions officers brought her to a nearby public-welfare midwife where

she gave birth to a baby boy. Pallet was just seventeen at the time.

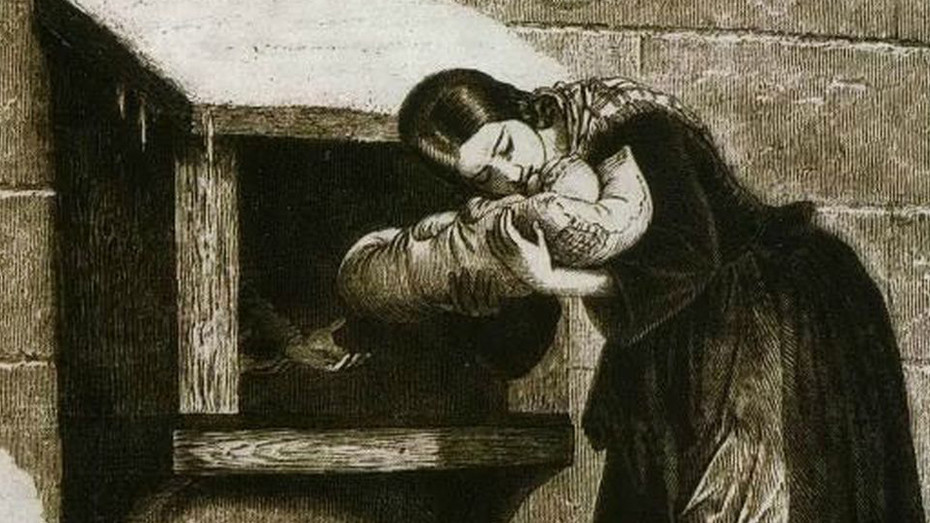

Not wanting to abandon her baby, as

she herself had been abandoned, she breastfed her infant for two months,

then weaned him so she could go back to work. Ernestine wanted to marry,

but whenever she suggested it to Eugene, he laughed at her. He provided

no child support and also squandered all of Ernestine's earnings on

drink and gambling. On January 31, 1880, Eugene took all their money, 65

Francs, and left her and their infant son without food or resources.

Ernestine had no money and neither she nor her baby had anything to eat.

Not wanting to beg in the street , she asked a neighbor for help, but

that neighbor refused her. She dared not ask her aunt for help because

of the argument over her relationship with Eugene. His mother, with whom

he lived much of the time, had helped out with child care and food, but

had refused further help without remuneration because Ernestine and

Eugene earned good wages. She could earn 4 francs, and he earned 7

Francs, on days that they worked.

On the

second day without food, as she later testified , she had gone to the

offices of Public Assistance. She went to one office where she hoped to

abandon her baby; but officials deterred her. At another office she

sought immediate assistance, and when she finally saw an official, he

told her to return in a week because he had to conduct an investigation

to find out if it were true that she "was dying of hunger." She left in

tears, denied help from Public Assistance and without any food for her

hungry and crying baby. In desperation, overcome by madness, she

claimed, she strangled her

baby and then told everyone that she

had abandoned

him

to Enfants Assistes.

Ernestine loved this man

who battered

her, and she became pregnant again. In

May of 1881, almost

nine months pregnant, she finally left

Eugene because of his abuse. She sought admission to la Maternite , but

was refused because she was not in labor. Not wanting to return to her

violent lover, she turned herself in to the police for the crime of

infanticide that she had committed in February 1880. The jury convicted

her of murder, but with extenuating circumstances. She had to serve five

years in prison, in part

because of testimony from public

officials that

there was no record of her asking for

assistance, and that bureaucrats at Public Assistance never tell a woman

that she has to wait eight days. Furthermore, officials averred,

Ernestine could have employed other strategies to save her son and

herself.

Ernestine loved this man

who battered

her, and she became pregnant again. In

May of 1881, almost

nine months pregnant, she finally left

Eugene because of his abuse. She sought admission to la Maternite , but

was refused because she was not in labor. Not wanting to return to her

violent lover, she turned herself in to the police for the crime of

infanticide that she had committed in February 1880. The jury convicted

her of murder, but with extenuating circumstances. She had to serve five

years in prison, in part

because of testimony from public

officials that

there was no record of her asking for

assistance, and that bureaucrats at Public Assistance never tell a woman

that she has to wait eight days. Furthermore, officials averred,

Ernestine could have employed other strategies to save her son and

herself.

The story

of Ernestine Pallet illustrates the limited choices open to a desperate

woman who was poor

and

pregnant in

Paris.

It shows the failure of neighborhood

and family networks to help her and the failure of private charity or

public assistance to come to her relief in 1880. It also highlights the

importance of public hospitals and midwives to Ernestine in 1879 and in

1881, and to her mother in 1862, while it

raises questions about how poor women

managed in France's largest city.