Alistair Horne, The Fall of Paris

Technology under Siege, 2: Pigeons and Microfilm

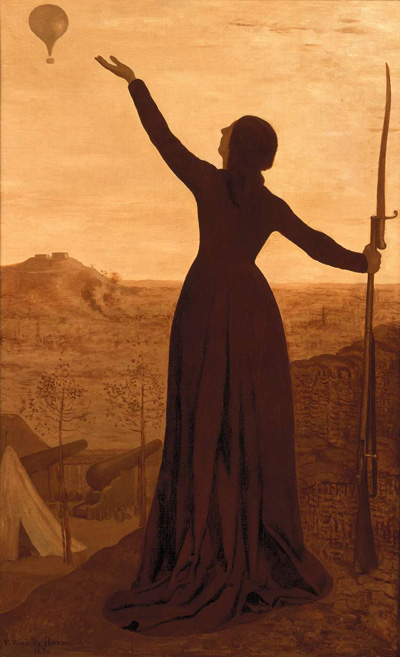

Horne has just described the use of balloons to get messages out of Paris during the siege. In this passage he describes efforts to get messages back into the city.

A more intractable problem was that the balloons afforded only a one-sided means of communication. . .

Other methods devised for communicating with Paris included a submarine, and glass globules that were to be floated down the Seine (but

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes - The Balloon (1870) |

unfortunately it froze); and one balloon even carried with it divers' suits with a similar project inmind (but unfortunately it landed in Bavaria). Five messenger dogs were used (unsuccessfully) and several brave footcouriers

hired to run the blockade. With great ingenuity they secreted minuscule messages in hollow-buttons, in the soles of their shoes, and even in slits under their skins; but most of them were caught and several were shot. Only one, a postman called Létoile Simon, succeeded in making the trip both ways, and he was awarded the Médaille Militaire.

The humble carrier-pigeon was to prove the only means of breaking the blockade in reverse. In Paris there was an expert in microphotography called Dagron, who before the war had invented a ring called a 'stanhope' containing a tiny' photograph magnified by a gem-like lens, a novelty that had sold in vast, quantities at the Great Exhibition of 1867. Early on November 12th. Dagron and his equipment had set out from Paris in two balloons, the Niepce and the Daguerre. Both were blown towards the east; before the horrified eyes of Dagron in the Niepce, the Daguerre came down and was promptly seized by Prussians. When the crew of the Niepce desperately tried to gain altitude by heaping out ballast, the sacks of sand proved to be rotten and burst in the gondola. All fell to bailing out the sand with Dagron's photographic beakers; some of the precious equipment had to be jettisoned too, but ,the Niepce escaped. Eventually Dagron reached Tours, where, although badly handicapped and delayed by, the loss of equipment, he set up the first microphotography unit ever to be employed in war. Government dispatches in Tours were reduced to a minute size, printed on feathery collodion membranes, then rolled into a pellicle; so that one pigeon could carry up to 40,000 dispatches, equivalent to the contents of a complete book. On reaching Paris, the dispatches were projected by magic lantern and transcribed by a battery of clerks. Sometimes one pigeon-load alone would require a whole week to decipher and distribute. As well as carrying official messages, the pigeons were entrusted with a vast amount of precious personal correspondence. . . .

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, The Pigeon, (1871) |

In the course of the Siege, 302 birds were sent off, of which 59 actually reached Paris. The remainder were taken by birds of prey, died of cold and hunger, or ended in Prussian pies.3 Some of those captured on board the Daguerre were released by the Prussians, carrying demoralizing 'deception" messages. But they were betrayed by their suspiciously Germanic wording, as well as by being signed by an 'André Lavertujon', who had in fact never left Paris, The great drawback to the pigeon post was its unreliability and, as the days grew shorter, the arrival of the pigeons -- unable to fly by night-became increasingly erratic. One, released at Orléans on November 18th, did not in fact reach Paris until February 6th, a week after the Siege ended. But although . . . the strategic role of the aerial posts was limited, their effect on civilian morale in Paris was incalculably great.