Alistair Horne, The Fall of Paris

Technology under Siege, 1: Balloons

8. A TOUCH OF VERNE

WHEN, at the beginning of October, a Frenchwoman in Prussian-occupied Versailles first saw a balloon rising out of Paris she exclaimed in the  hearing of Russell of The Times: 'Paris reduced to that! Oh good God! Have pity on us!' Yet the balloons of Paris were to constitute probably the most illustrious single episode of the Siege. To the average person today, the Siege of Paris evokes principally two images: rateating and balloons. The first represents the depths to which a modern civilization can be reduced; the second, the zenith

hearing of Russell of The Times: 'Paris reduced to that! Oh good God! Have pity on us!' Yet the balloons of Paris were to constitute probably the most illustrious single episode of the Siege. To the average person today, the Siege of Paris evokes principally two images: rateating and balloons. The first represents the depths to which a modern civilization can be reduced; the second, the zenith

of its resourcefulness in adversity.

The development of the balloon had always been a preserve of the inventor nation. De Montgolfier's first 'hot-air' balloon of 1783 was a perilous device in which the passengers had to stoke a fire with straw and wood immediately beneath the highly inflammable paper envelope; so perilous, indeed, that Louis XVI had proposed that the first manned flight be made by two criminals under sentence of death. In fact it was carried out by Pilâtre de Rozier and the Marquis d'Arlandes, who flew for twenty-five minutes across Paris, at a height of three hundred feet. Almost simultaneously, a French physicist, Professor Charles, was experimenting with a hydrogen-filled balloon, which made its first ascent from the Tuileries in December 1783. When someone cast doubts on the usefulness of Charles's invention, one of the spectators, Benjamin Franklin, was provoked to make a famous retort: 'Of what use is the new-born baby?' Two years later, Blanchard managed to cross the Channel in a charliere (throwing out even his own trousers in an endeavour to maintain altitude), for which feat he earned £50 and a life pension from Louis XVI. . . .

As early as 1793, the French were using balloons for military purposes- to carry dispatches over the heads of the enemy -- and the following year Robespierre established an 'Ecole Aerostatique' at Meudon. This was closed down by Napoleon I; perhaps one of the few instances where he showed less prescience than his tragic nephew. For Napoleon III at least appreciated the military potentialities of balloons, and had employed a man called Nadar to spy out Austrian positions at Solferino. . .

When the Siege of Paris began, there were only seven existing balloons in the city, most of them in disrepair. Symbolically, the Imperial, which had arrived just too late to observe the dynasty triumph at Solferino,- was in shreds; the Celeste, which by giving captive flights had dazzled visitors to the Great Exhibition of 1867 with French prowess, was described as being as gas-tight as a 'sieve'. But undismayed the intrepid French aeronauts at once went to work; literally, with paste-pot and paper. Within two days of the closing of the ring, the first balloon was prepared for flight, but burst while being inflated. That same day, however, Nadar carried out a successful reconnaissance of the Prussian lines. The corpulent Nadar was a man of many talents -- photographer, caricaturist, journalist, and a friend of the Impressionists (It was in, his house that Renoir held one of his first exhibitions). . . . He also appears to have been an astute businessman; Nadar's enemies later accused him of dropping advertisements for his own company over the Prussian outposts, instead of propaganda leaflets!

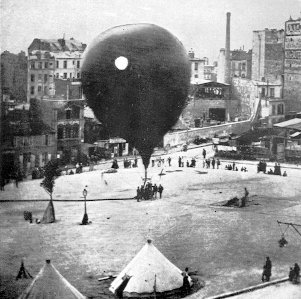

On September 23rd, Durouf made his successful solo flight to Evreux and three days later the Minister of Posts, M. Rampont, 'decreed the establishment of a 'Balloon Post'. Among the first to be invited to send a letter by it was the eighty-six-year-old daughter of the inventor, Mlle de Montgolfier. . . .

After Durouf, balloons took off at a rate of about two or three a week usually from an empty space at the foot of the Solferino Tower on top of Montmartre, or from outside the Gare du Nord and the Gare d'Orleans. Godard, one of a family of veteran aeronauts, got away successfully suspended from two small balloons lashed together and appropriately named Les Etats-Unis. Tissandier, flying in the patched-up Celeste, which in peacetime had never been capable of staying in the air for more than thirty-five minutes, managed to reach Dreux (fifty miles from Paris') after passing so low over Versailles that he could see Prussian soldiers sunbathing on the lawns. Lutz, travelling aboard the Ville de Florence,

found himself descending rapidly into the Seine, and was forced to jettison a sack full of top-secret Government dispatches. Remarkably enough, it was returned to him on landing by some peasants, and he managed to escape with them through the Prussian lines to Tours, disguised as a cowherd. . . .

. . . looking back from this age of science, it does seem little less than miraculous that so many of the French balloonists succeeded in getting through. It was not until the eighteenth flight on October 25th that a manned balloon (curiously enough named the Montgolfier) fell into Prussian hands. Equipment was incredibly primitive. The balloons themselves were constructed simply of varnished cotton, because silk was unobtainable, and filled with highly explosive coal-gas; thus they were exceptionally vulnerable to Prussian sharp-shooters. Capable of unpredictable motion in all three dimensions, none of which was controllable in inexperienced hands they had an unpleasant habit of shooting suddenly up to six thousand feet, then falling back again almost to ground-level. Huddled in their baskets (which Bowles noted to his horror were only 'the height of a man's waist, with just enough room for two people to sit or rather squat'), devoid of any protection from the elements, the balloonists suffered agonizingly from cold as the winter grew more bitter. . . . Often the aeronauts carried no compass, and after a few minutes of twisting, giddy progress they had in any case lost all sense of direction.

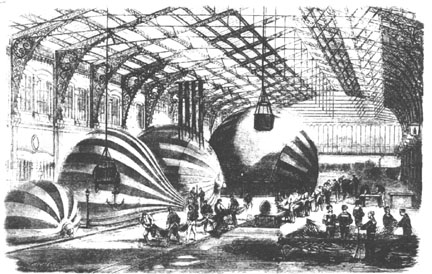

Balloons being produced in a Paris Train Station |

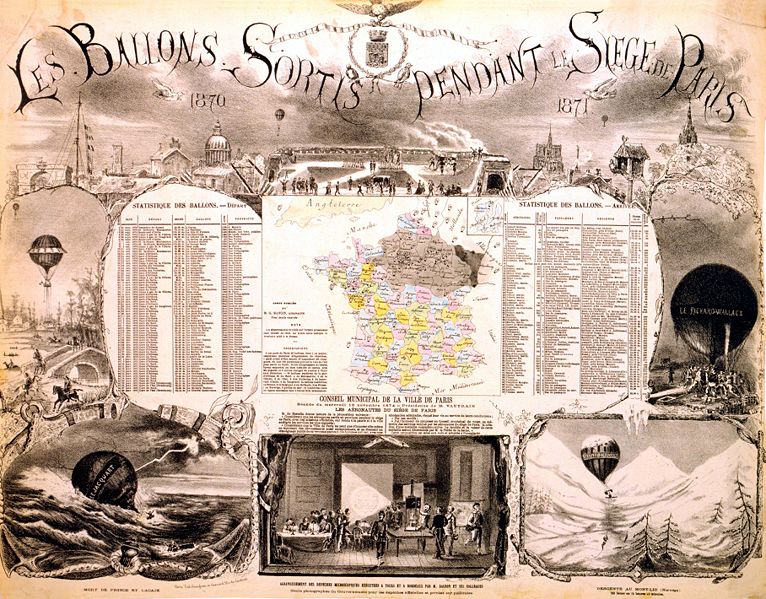

To every corner of France -- and beyond -- the winds blew them, and they seldom had the remotest idea where they were on landing. Added to this, since a frustrated Bismarck had proclaimed that he would submit any apprehended balloonists to the fate of common line-crossers, there was always the prospect of a Prussian bullet at the end of each flight (although, on hearing of the Prussian threat, another 172 aeronauts had promptly volunteered).

In the deserted halls of the Gare d'Orléans, Eugène Godard, veteran of some eight hundred flights, had set up an assembly line for fabricating balloons, and scattered across Paris were small ancillary workshops. Conducted by Nadar to a former dance-hall at Montmartre, Théophile Gautier found some sixty young women sewing away with furious industry, reminding him of the 'humming of old-fashioned spinning-wheels'. At the Gare du Nord, where rails already rusted over with grass beginning to grow between them made Bowles think of the Sleeping Beauty, the completed balloons were varnished; stretched out, partially inflated, Iike rows of massive whales. In the waiting-rooms here and at the Gare du Nord, sailors were busv braiding ropes and halliards. . . .

Where could sufficient numbers of trained aeronauts be found to man the balloons? Soon the "professionals" would all have flown out of Paris. Goddard solved this by setting up a training-school within the factory. Baskets were suspended from the station girders, containing all the essential controls to simulate flight -- valves, ballast, guide-ropes, etc. Godard's sailors in-particular (possibly because they were less prone to sea-sickness) proved themselves markedly proficient in a short time; of the 65 balloons that left Paris during the Siege, only 18 were piloted by professionals, 17 by volunteers, and the remaining 30 by sailor.

Broadside with map of where the balloons landed during the siege and a list of the pilots