Sarah Bernhardt, My Double Life

Sarah Berhardt, the most celebrated French actress of the century, devoted a section of her autobiography to her experiencesduring the siege of Paris

PARIS BOMBARDED

The month of January arrived. The army of

the enemy held Paris day by day in a still closer grip. Food was

getting scarce. Bitter cold enveloped the city, and poor soldiers who

fell, sometimes only slightly wounded, passed away gently in a sleep

that was eternal, their brain numbed and their body half frozen.

No more news could be received from outside, but thanks to the United States Minister, who had resolved to remain in Paris, a letter arrived from time to time. It was in this way that I received a thin slip of paper, as soft as a primrose petal, bringing me the following message: "Every one well. Courage. A thousand kisses.—Your mother." This impalpable missive dated from seventeen days previously. . . .

M. Herisson, the mayor, with some

functionary holding an influential post, had been to inspect my

ambulance. The important personage had  requested

me to have the beautiful white Virgins which were on the mantel-pieces

and tables taken away, as well as the Divine Crucified—one hanging on

the wall of each room in which there were any of the wounded. I refused

in a somewhat insolent and very decided way to act in accordance with

the wish of my visitor, whereupon the famous Republican turned his back

on me and gave orders that I should be refused everything at the Mairie.

I was very determined, however, and I moved heaven and earth until I

succeeded in getting inscribed on the lists for distribution of food,

in spite of the orders of the chief. It is only fair to say that the

mayor was a charming man. . . .

requested

me to have the beautiful white Virgins which were on the mantel-pieces

and tables taken away, as well as the Divine Crucified—one hanging on

the wall of each room in which there were any of the wounded. I refused

in a somewhat insolent and very decided way to act in accordance with

the wish of my visitor, whereupon the famous Republican turned his back

on me and gave orders that I should be refused everything at the Mairie.

I was very determined, however, and I moved heaven and earth until I

succeeded in getting inscribed on the lists for distribution of food,

in spite of the orders of the chief. It is only fair to say that the

mayor was a charming man. . . .

I told the head attendant to open the

largest of the bottles, in which through the thick glass we could see an

enormous piece of beef surrounded by thick, muddled-looking water. The

string fastened round the rough paper which hid the cork was cut, and

then, just as the man was about to put the corkscrew in, a deafening

explosion was heard and a rank odour filled the room. Every one rushed

away terrified. I called them all back, scared and disgusted as they

were, and showed them the following words on the directions: "Do not be

alarmed at the bad odour on opening the bottle." Courageously and with

resignation we resumed our work, though we felt sick all the time from

the abominable exhalation. I took the beef out and placed it on a dish

that had been brought for the purpose. Five minutes later this meat

turned blue and then black, and the stench from it was so unbearable

that I decided to throw it away. Madame Lambquin was wiser, though, and

more reasonable.

"No, oh no, my dear girl," she said; "in

these times it will not do to throw meat away, even though it may be

rotten. Let us put it in the glass bottle again and send it back to the

Mairie."

I followed her wise advice, and it was a very good thing I did, for another ambulance, installed at Boulevard Medicis, on opening these bottles of meat had been as horrified as we were, and had thrown the contents into the street. A few minutes after the crowd had gathered round in a mob, and, refusing to listen to anything, had yelled out insults addressed to "the aristocrats," "the clericals," and "the traitors," who were throwing good meat, intended for the sick, into the street, so that the dogs were enjoying it, while the people were starving with hunger, &c. &c.

It was with the greatest difficulty that the wretched, mad people had been prevented from invading the ambulance, and when one of the unfortunate nurses had gone out, later on, she had been mobbed and beaten until she was left half dead from fright and blows. . . .As we could not count on this preserved meat

for our food, I made a contract with a knacker, who agreed to supply

me, at rather a high price, with horse flesh, and until the end this was

the only meat we had to eat. Well prepared and well seasoned, it was

very good.

Hope had now fled from all hearts, and we were living in the expectation of we knew not what. An atmosphere of misfortune seemed to hang like lead over us, and it was a sort of relief when the bombardment commenced on December 27.

At last we felt that something new was

happening! It was an era of fresh suffering. There was some stir, at any

rate. For the last fortnight the fact of not knowing anything had been

killing us.

On January 1, 1871, we lifted our glasses to the health of the absent ones, to the repose of the dead, and the toast choked us with such a lump in our throats. . . .

The bombardment continued, and the ambulance flag certainly served as a target for our enemies, for they fired with surprising exactitude, and altered their firing directly a bomb fell any distance from the neighbourhood of the Luxembourg. Thanks to this, we had more than twelve bombs one night. These dismal shells, when they burst in the air, were like the fireworks at a fête. The shining splinters then fell down, black and deadly. . . .

On January 10, Madame Guérard and I were

sitting up at night, on one of the lounges in the green-room, awaiting

the dismal cry of "Ambulance!" There had been a fierce affray at

Clamart, and we knew there would be many wounded. I was telling her of

my fear that the bombs which had already reached the Museum, the

Sorbonne, the Salpétrière, the Val-de-Grâce, &c., would fall on the

Odéon.

"Oh, but, my dear Sarah," said the sweet woman,

"the ambulance flag is waving so high above it that there could be no

mistake. If it were struck it would be purposely, and that would be

abominable."

"But, Guérard," I replied, "why should you

expect these execrable enemies of ours to be better than we are

ourselves? Did we not behave like savages at Berlin in 1806?"

"But at Paris there are such admirable public monuments," she urged.

"Well, and was not Moscow full of masterpieces?

The Kremlin is one of the finest buildings in the world. That did not

prevent us giving that admirable city up to pillage. Oh no, my poor petit Dame, do not deceive yourself. Armies may be Russian, German, French, or Spanish, but they are

armies—that is, they are beings which form an impersonal 'whole,' a

'whole' that is ferocious and irresponsible. The Germans will bombard

the whole of Paris if the possibility of doing so should be offered

them. You must make up your mind to that, my dear Guérard——"

I had not finished my sentence when a terrible

detonation roused the whole neighbourhood from its slumbers. Madame

Guérard and I had been seated opposite each other. We found ourselves

standing up close together in the middle of the room, terrified. My

poor cook, her face quite white, came to me for safety. The detonations

continued rather frequently. The bombarding had commenced from our

side that night. I went round to the wounded men, but they did not seem

to be much disturbed. Only one, a boy of fifteen, whom we had surnamed

"pink baby," was sitting up in bed. When I went to him to soothe him

he showed me his little medal of the Holy Virgin.

"It is thanks to her that I was not killed," he said. "If they would put the Holy Virgin on the ramparts of Paris the bombs would not come." . . .

We spent several hours at the little round

window of my dressing—room, which looked out towards Chatillon. It was

from there that the Germans fired the most.

We listened, in the silence of the night, to

the muffled sounds coming from yonder; there would be a light, a

formidable noise in the distance, and the bomb arrived, falling in front

of us or behind, bursting either in the air or on reaching its goal.

Once we had only just time to draw back quickly, and even then the

disturbance in the atmosphere affected us so violently that for a

second we were under the impression that we had been struck.

The shell had fallen just underneath my

dressing-room, grazing the cornice, which it dragged down in its fall to

the ground, where it burst feebly. But what was our amazement to see a

little crowd of children swoop down on the burning pieces, just like a

lot of sparrows on fresh manure when the carriage has passed! The

little vagabonds were quarrelling over the débris of these engines of warfare. I wondered what they could possibly do with them.

"Oh, there is not much mystery about it," said Boyer; "these little starving urchins will sell them."

This proved to be true. One of the men

attendants, whom I sent to find out, brought back with him a child of

about ten years old.

"What are you going to do with that, my little

man?" I asked him, picking up the piece of shell, which was warm and

still dangerous, on the edge where it had burst.

"I am going to sell it," he replied.

"What for?"

"To buy my turn in the _queue when the meat is being distributed."

"But you risk your life, my poor child.

Sometimes the shells come quickly, one after the other. Where were you

when this one fell?"

"Lying down on the stone of the wall that

supports the iron railings." He pointed across to the Luxembourg

Gardens, opposite the stage entrance to the Odéon.

We bought up all the débris that the child had, without attempting to give him advice which might have sounded wise. What was the use of preaching wisdom to this poor little creature, who heard of nothing but massacres, fire, revenge, retaliation, and all the rest of it, for the sake of honour, for the sake of religion, for the sake of right? Besides, how was it possible to keep out of the way? All the people living in the Faubourg St. Germain were liable to be blown to pieces, as the enemy very luckily could only bombard Paris on that side, and not at every point. No; we were certainly in the most dangerous neighbourhood.

.

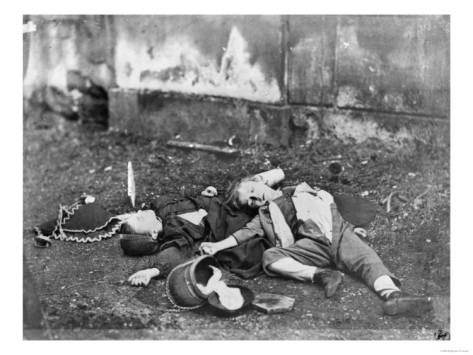

.. One day Baron Larrey came to see Frantz Mayer, who was very ill. He

wrote a prescription which a young errand boy was told to wait for and

bring back very, very quickly. As the boy was rather given to

loitering, I went to the window. His name was Victor, but we called him

"Toto." The druggist lived at the corner of the Place Medicis. It was

then six o'clock in the evening. Toto looked up, and on seeing me he

began to laugh and jump as he hurried to the druggist's. He had only

five or six more yards to go, and as he turned round to look up at my

window I clapped my hands and called out, "Good! Be quick back!" Alas!

Before the poor boy could open his mouth to reply he was cut in two by a

shell which had just fallen. It did not burst, but bounced a yard

high, and then struck poor Toto right in the middle of the chest. I

uttered such a shriek that every one came rushing to me. I could not

speak, but pushed every one aside and rushed downstairs, beckoning for

some one to come with me. "A litter"—"the boy"—"the druggist"—I managed

to articulate. Ah, what a horror, what an awful horror! When we

reached the poor child his intestines were all over the ground, his

chest and his poor little red chubby face had the flesh entirely taken

off. He had neither eyes, nose, nor mouth; nothing, nothing but some

hair at the end of a shapeless, bleeding mass, a yard away from his

head. It was as though a tiger had torn open the body with its claws

and emptied it with fury and a refinement of cruelty, leaving nothing

but the poor little skeleton.

.

.. One day Baron Larrey came to see Frantz Mayer, who was very ill. He

wrote a prescription which a young errand boy was told to wait for and

bring back very, very quickly. As the boy was rather given to

loitering, I went to the window. His name was Victor, but we called him

"Toto." The druggist lived at the corner of the Place Medicis. It was

then six o'clock in the evening. Toto looked up, and on seeing me he

began to laugh and jump as he hurried to the druggist's. He had only

five or six more yards to go, and as he turned round to look up at my

window I clapped my hands and called out, "Good! Be quick back!" Alas!

Before the poor boy could open his mouth to reply he was cut in two by a

shell which had just fallen. It did not burst, but bounced a yard

high, and then struck poor Toto right in the middle of the chest. I

uttered such a shriek that every one came rushing to me. I could not

speak, but pushed every one aside and rushed downstairs, beckoning for

some one to come with me. "A litter"—"the boy"—"the druggist"—I managed

to articulate. Ah, what a horror, what an awful horror! When we

reached the poor child his intestines were all over the ground, his

chest and his poor little red chubby face had the flesh entirely taken

off. He had neither eyes, nose, nor mouth; nothing, nothing but some

hair at the end of a shapeless, bleeding mass, a yard away from his

head. It was as though a tiger had torn open the body with its claws

and emptied it with fury and a refinement of cruelty, leaving nothing

but the poor little skeleton.

Baron Larrey, who was the best of men, turned slightly pale at this sight. He saw plenty such, certainly, but this poor little fellow was a quite useless holocaust. Ah, the injustice, the infamy of war! Will the much dreamed of time never come when wars are no longer possible; when the monarch who wants war will be dethroned and imprisoned as a malefactor? Will the time never come when there will be a cosmopolitan council, where a wise man of every country will represent his nation, and where the rights of humanity will be discussed and respected? So many men think as I do, so many women talk as I do, and yet nothing is done. The pusillanimity of an Oriental, the ill-humour of a sovereign, may still bring thousands of men face to face. And there will still be men who are so learned, chemists who spend their time in dreaming about, and inventing a powder to blow everything up, bombs that will wound twenty or thirty men, guns repeating their deadly task until the bullets fall, spent themselves, after having torn open ten or twelve human breasts. . . .