The Defense of Louise Michel

From Louise Michels, My Trials (http://communeeditions.com/2013/10/08/my-trials-by-louise-michel/)

Interrogation of the Defendant

Judge: You have heard the acts of which you are accused. What do you have to say in your defense?

Defendant: I don’t want to defend myself. I don’t want to be defended.

I belong entirely to the social revolution, and I declare that I accept

responsibility for all my actions. I accept it completely and without qualification. You accuse me of being involved in the killing of the generals?

To that, I would answer yes, if I had found myself in Montmartre when

they wanted to fire on the people; I would not have hesitated to fire on

those who gave orders like those; but as soon as they were prisoners, I

don’t understand why they were shot, and I consider that act as one of remarkable cowardice!

I accept it completely and without qualification. You accuse me of being involved in the killing of the generals?

To that, I would answer yes, if I had found myself in Montmartre when

they wanted to fire on the people; I would not have hesitated to fire on

those who gave orders like those; but as soon as they were prisoners, I

don’t understand why they were shot, and I consider that act as one of remarkable cowardice!

As for the burning of Paris, yes, I participated in it. I wanted to put up

a barrier of flames to the invaders of Versailles. I had no accomplices, I

acted on my own.

You also say that I am an accomplice of the Commune! Of course I

am, since the Commune wanted social revolution above all, and social

revolution is my dearest wish. What is more, I am honored to be counted

among the promoters of the Commune which, in any case, was absolutely

not, absolutely not involved, as you well know, with the assassinations and

the burnings: I attended all of the meetings at the Hôtel de Ville, and I

affirm that there was never any question of assassination or burning. Do

you want to know who the real culprits are? The police. Later, perhaps,

light will shine on these events for which it is today so natural for us to

blame all the partisans of social revolution. . . .

Judge: In a proclamation, you said that every twenty-four hours a hostage

should be shot?

Answer: No, I only wanted to threaten. But why would I defend myself?

I’ve already told you I refuse to do it. You are the men who are going to

judge me; you’re in front of me openly; you are men, and I, I am only a

woman. And yet I look you straight in the face. I know very well that anything I tell you will not change my sentence in the slightest. Thus I have

a single and final word before I sit down. We have never wanted anything

but the triumph of the principles of the Revolution. I swear to it by our

martyrs fallen on the field of Satory, by our martyrs I still acclaim openly

here, and who will someday find an avenger.

Once again, I belong to you; do with me as you please. Take my life

if you want it. I am not a woman who would dispute your wishes a single

instant.

Judge:

You declare that you did not approve of the assassination of the

generals, and yet people say that, when you learned of it, you shouted, “They shot them. It serves them right.”

A: Yes, I said that, I admit it. (I even recall that it was in the presence of

citizens Le Moussu and Ferré.)

Q: So you approved of the assassination?

A: If I may, what I said is not proof. The words that I spoke aimed at

encouraging the revolutionary impulse.

Q: You also wrote in newspapers. In Le Cri du peuple, for example?

A:

Yes, I don’t hide it.

Q: Every day these newspapers called for the confiscation of the clergy’s

property and other similar revolutionary measures. Such were your opinions, then?

A: Of course. But note that we had never wanted to take those goods for

ourselves. We thought only to give them to the people for their well-being.

Q: You called for the abolition of the magistrature?

A: Because I always had in front of me examples of its errors. I remember the Lesurques affair and so many others.

Q:

You acknowledge wanting to assassinate M. Thiers?

A: Certainly... I said it already and I say it again.

Q:

It seems that you wore various costumes during the Commune.

A: I dressed as usual. I added only a red sash to my clothing.

Q: Didn’t you wear men’s clothing several times?

A: A single time: it was March 18th. I dressed as a National Guardsman, so I wouldn’t attract attention. . . .

Judge: Accused, do you have something to say in your defense?

Louise Michel: What I demand from you, you who claim to be the war

council, who present yourselves as my judges, who do not hide like the

Board of Pardons, from you who are military men and who judge me

openly, it is the field of Satory that I demand, where our brothers have

already fallen.

I must be removed from society; that’s what you’ve been told to do.

Well, the prosecutor is right! Since it seems that every heart that beats for

freedom has no right to anything but a bit of lead, I demand my share!

If you let me live, I will never cease crying out for vengeance, and I will

denounce the assassins of the Board of Pardons to the vengeance of my

brothers...

Judge: I cannot let you speak if you continue in that tone.

Louise Michel: I’m finished... If you are not cowards, kill me...

After these words, which caused a great stir in the audience, the council withdraws to deliberate. After a few minutes it returned in session, and, at the end of the verdict, Louise Michel is unanimously sentenced to deportation to a fortified place.

Louise Michel was led back in and informed of the verdict. When the clerk told her that she had twenty-four hours to apply for judicial review, she cried, “No! There is nothing to appeal. But I should prefer death!”

Louise Michel was sent to a prison camp on the island of New Caledonia in the South Pacific. She taught the children of the other deportees and worked with the indigenous Kanak population on the island. She participated in two revolts of the Kanaks against their colonial rulers. In 1880 there was a general amnesty of the Communards, and she returned to France where she continued political organizing until her death in 1905. She has remained a hero of the French Left.

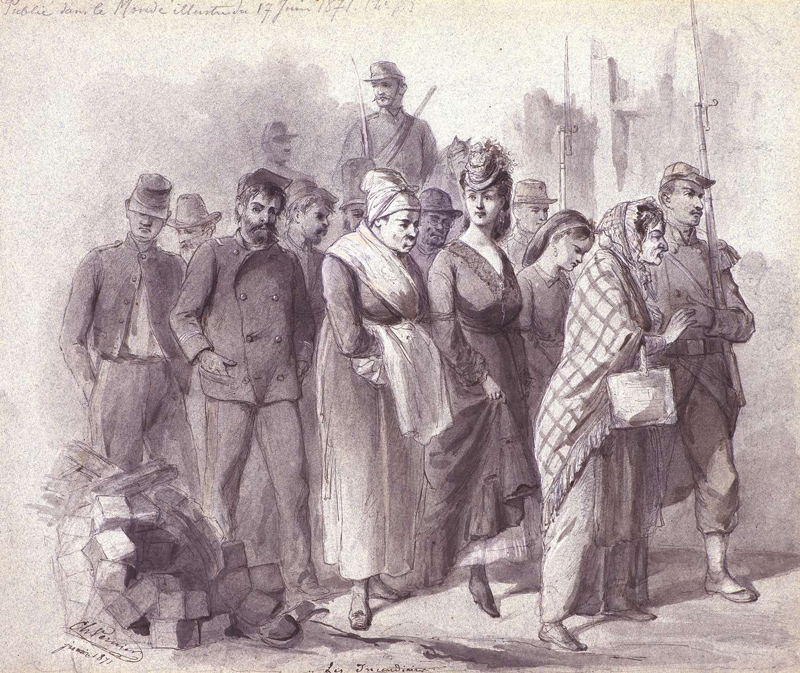

Captured Communards