|

The

authorities

felt

helpless

in

the

whirlwind

of

what

soon

became

a

full-scale

revolt.

Policemen

avoided

working-class districts,

where

some

been

set

upon

violently.

A

mob

forced

the

warden

of

Sainte

Pelagie

to

free

demonstrators

interned

since

January,

and

another

raided

the

Gobelins

police

barracks

for

its

stock

of

chassepot

rifles.

Pillaging

spread

throughout

the

city,

which

armed

itself

against

inva

sion.

Until

Bismarck

agreed

not

to

occupy

Paris,

National

Guards

kept

close

watch

at

artillery

parks

situated

on

Montmartre

and

Belleville,

Adolphe Thiers rode up from Bordeaux in high dudgeon, and his reappearance was a spark to tinder. Although this eloquent Provenc;:al had fought hard against Napoleon III, working-class Frenchmen hated him for sins older than the Second Empire: he still bore the nickname "Pere Transnonain" almost forty years after the "massacre of the rue Transnonain," when as Louis Philippe's interior minister he had or dered General Bugeaud to crush striking Lyonnais silk workers. People had also not forgotten his denunciation of the "vile multitude" in June 1848, when yet another massacre took place, nor his advocacy of an electoral law with residence requirements calculated to disenfranchise some two hundred thousand Parisians. Thiers may have shrunk since then, but the little man who had written volumes about Napoleon I had yielded nothing of his belief in the sacredness of private property. All five feet of him argued a political vision that impeached the nomad, the immigrant, the socialist, the crowd. "We have always desired free dom," he once proclaimed. "Not the freedom of factions but that which shelters affairs of state from the twofold influence of Courts and of Streets."

Far

from

seeking

to

assuage

the

National

Guard

or

the

Central

Committee

it

elected

midway

through

March,

Thiers

resolved

to

sweep

aside

this

mutinous

group

with

a

coup

de

main

and

subjugate

Paris

before

the

Assembly

reconvened

in

Versailles.

His

chief

objective

was

the

gun

park

atop

Montmartre,

where

171

cannon

made

a

formidable

battery.

Early

on

the

morning

of

March

18,

General

Paturel

cordoned

off

lower

Montmartre

between

Clichy

and

Pigalle,

as

troops

led

by

General

Lecomte

marched

south

from

Clignancourt.

The

operation

ran

smoothly

until

they

seized

the

guns.

It

then

became

clear

that

since

they

were

without

equipment

to

transport

heavy

artillery

down

hill

nothing

had

been

accomplished,

and

time

spent

in

summoning

horse

teams

proved

fatal.

At

dawn

Montmartre

was

still

asleep,

but

two

hours

later

the

army

found

itself

marooned

in

a

sea

of

villagers,

among

whom

women

greatly

outnumbered

men.

"By

the

time

a

column

of

National

Guards

arrived

the

essential

distance

between

troops

and

citizens

had

become

gravely

compromised,"

writes

one

historian.

Two

National

Guard officers

stepped

forward to

parley with

the

line.

The

rest

of

the

Guards

and

the

soldiers who

had

already

joined

with

them

raised

the

butts

of

command.

Women

from

the

crowd

thrust

themselves

between

the

two

groups,

shouting

to

the

troops,

"Will

you

fire

on

us?

On

your

brothers?

Our

husband

s?

Our

children?"

Four

times

Lecomte

vainly

ordered

his

men

to fire.

In

this

expectant silence

warrant

officer

Verdaguer

called

on

his

fellow

soldiers

to

ground

their

arms

and

the

crowd

surged

forward

to

embrace

the

troops,

crying "Long

live

the

line."

The

gendarmes

were

overrun

and

disarmed

before

they

could

fire,

the

officers

were

pulled

off

their

horses

and

Lecomte

himself

was

seized.

By

nine

in

the

morning

it

was

all

over.

For

Thiers,

reports

of

troops

breaking

ranks

all

over

town

brought

back

memories

of

February

1848.

On

that

occasion

he

had

urged

King

Louis

Philippe

to

leave

Paris

and

recapture

it

from

without.

Louis

Philippe

had

rejected

his

advice,

but

now

God

alone

stood

above

Thiers.

No

sooner

had

he

beaten

a

retreat

than

he

issued

general

evac

uation

orders,

spurning

colleagues

who

felt

that

the

army

should

en

trench

itself

at

the

Ecole

Militaire

or

in

the

Bois

de

Boulogne.

Forty

thousand

men

were

thus

marched

out

of

Paris,

never

to

serve

again.

Up

from

the

provinces

came

fresh

recruits

"uncontaminated"

by

the

capital,

and

before

long

100,000

men

occupied

camps

around

Ver

sailles.

The

day

of

reckoning

was

imminent,

Thiers

proclaimed

on

March

20,

reassuring

not

only

antirevolutionary

Parisians

stranded

in

a

hostile

environment

but

Bismarck

as

well,

whose

patience

with

quar

relsome

Frenchmen

had

worn

thin.

Forty-eight

hours

later,

Versailles

took

over

where

Germany

had

left

off

several

months

earlier,

after

the

armistice.

It

declared

Paris

under

siege

once

again.

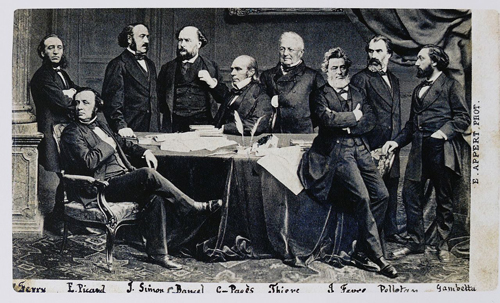

Adolf Thiers and the Provisional Government that was Engaged in Creating the Third Republic at Versailles