The Commune Becomes More Radical

Frederick Brown,

Zola: A Life

(New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 1995), pp.217-218.

Frederick Brown,

Zola: A Life

(New York: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 1995), pp.217-218.

Communards were spoiling for Armageddon as fervently as right-wing

deputies [of the Provisonal

Government at Versailles]. A movement whose initial goal had been

municipal independence soon consecrated the rift between the

ancien regime and the new order. "The communal revolution . . .

inaugurates a new era of scientific, positive , experimental politics,"

the Commune proclaimed on April 19 in a manifesto: "It's the end of the

old governmental and clerical world, of militarism, of bureaucracy, of

exploitation, of speculation, of monopolies, of privileges to which the

proletariat owes its servitude and the nation its disasters. May this

great, beloved fatherland deceived by lies and calumnies reassure

itself! The struggle between Paris and Versailles is of a kind that

cannot end in illusory compromises: the outcome will be unambiguous.

Victory pursued with irrepressible energy by the National Guards, is our

aim and our due. We appeal to France!

Throughout April, decrees rained thick and fast. Rent unpaid since

October 1870 was canceled. The grace period on overdue bills was

extended three years. Night work for bakery workers was made illegal. A

Labor and Exchange Commission authorized producers' cooperatives, of

which forty-three had come into existence by May 14, to take over

deserted ateliers. Mortmain property [that

owned by the Church] was nationalized when church was separated from

state. And anticlericalism fostered secular education. "Religious or

dogmatic instruction should . . . immediately and radically be

suppressed, for both sexes, in all schools and establishments supported

by the taxpayer," demanded Education Nouvelle, a group whose leader

subsequently helped individual school districts reform their curricula.

"Further, liturgical objects and religious images should be removed from

public view. Neither prayers, nor dogma, nor anything that pertains to

the individual conscience should be taught or practiced in common. Only

one method should hold sway, the experimental or scientific, which is

based upon the observation of facts, whatever their nature -- physical,

moral, intellectual." As priests and nuns were, of course, religious

images incarnate, most removed themselves from the classroom (except in

western Paris, where wealth defended tradition),

forcing Edouard Vaillant, the Commune's commissioner of

education, to open a recruitment center for teachers, or soi-disant [so-called] teachers, at City Hall.

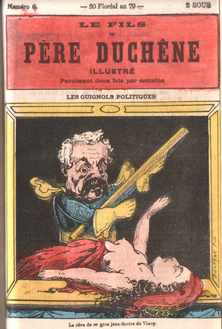

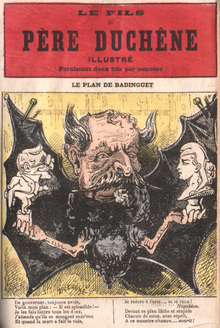

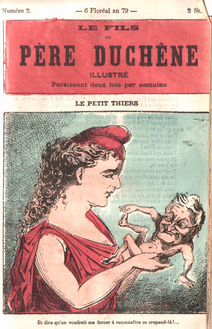

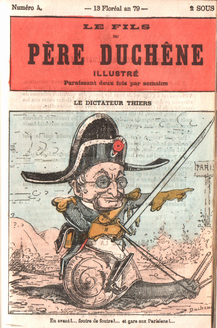

Little

newspapers (some, like Le Père

Duchesne, with names

that evoked the first

Revolution) multiplied

as fast as cooperatives, but

Little

newspapers (some, like Le Père

Duchesne, with names

that evoked the first

Revolution) multiplied

as fast as cooperatives, but many big ones vanished overnight, for the Commune, despite its professed

libertarianism, brooked no opposition from the bourgeois press. Freedom

stopped where treason began, and treason began wherever an editor fought

shy of direct democracy. First to disappear were Le Figaro

and Le

Gaulois. On

April 14 the Comité de

Sûreté Générale [the Committee on

General Security] had

Paris-Journal,

Le

Journal des débats,

Le Constitutionnel, and La

Liberté close shop. Two weeks later another purge silenced

La Cloche Le

Soir, Le Bien public,

and L'Opinion

nationale, with the Sûreté explaining how

dangerous it would be to countenance, in besieged Paris "newspapers that

openly preach civil war, give the

enemy strategic information, and calumniate defenders of the

Republic." Paranoia took

command as Versailles crept closer, and on May 5, when

La Petite Presse,

Le Petit Journal, and Le Temps

followed their brethren to the scaffold, they were dubbed "the most

active auxiliaries of the enemies of Paris and the Republic."

many big ones vanished overnight, for the Commune, despite its professed

libertarianism, brooked no opposition from the bourgeois press. Freedom

stopped where treason began, and treason began wherever an editor fought

shy of direct democracy. First to disappear were Le Figaro

and Le

Gaulois. On

April 14 the Comité de

Sûreté Générale [the Committee on

General Security] had

Paris-Journal,

Le

Journal des débats,

Le Constitutionnel, and La

Liberté close shop. Two weeks later another purge silenced

La Cloche Le

Soir, Le Bien public,

and L'Opinion

nationale, with the Sûreté explaining how

dangerous it would be to countenance, in besieged Paris "newspapers that

openly preach civil war, give the

enemy strategic information, and calumniate defenders of the

Republic." Paranoia took

command as Versailles crept closer, and on May 5, when

La Petite Presse,

Le Petit Journal, and Le Temps

followed their brethren to the scaffold, they were dubbed "the most

active auxiliaries of the enemies of Paris and the Republic."