Excerpts from The Journal of Edmond de Goncourt

September 11-12, 1870

Sunday, September 11

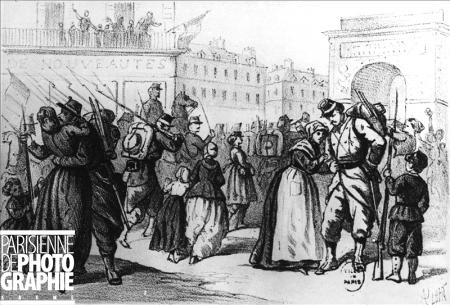

All along Boulevard Suchet, all along the road inside the fortifications, there is lively activity and large-scale movement on the part of the National Defense. All along the road they are making fascines and gabions, filling sacks of earth, hollow ing out powder magazines and oil storage dumps in the trenches. In the courtyard of the former customs collectors' barracks there is the dull resonance of cannon balls falling from the drays. Up above, civilians are carrying on cannon drill; down below, practice with breech loading rifles by the National Guards. Bands of silent workmen

pass by; the blue, white, and black blouses of Mobile Guards go by; and in the green channel of the railroad line the rapid flash of trains, of which you see only the top, covered with the red trousers, gold braid, epaulettes, and kepis of this huge military force improvised out of the civilian population. Everywhere in the midst of all this the headlong rush of little open carriages carrying curious, but slightly frightened women.

The Champ de Mars is still a camp, where soldierly gaiety has written on the grey canvas tents: We needmaids of all work. Endless files of horses go down to the Seine to drink and stand along the quay, where rope barriers enclose artillery horses and transport for the bridge builders.

go down to the Seine to drink and stand along the quay, where rope barriers enclose artillery horses and transport for the bridge builders.

The Champs Elysees, which is no longer being sprinkled, is a torment of dust through which you see an armed multitude and, now and then, the gleaming helmet of a dispatch-rider standing out at the foot of the avenue against the violet sky and the white obelisk.

In the Place de la Concorde a gathering of people completely in black at the base of the Strasbourg statue. Blouseclad men have made a human ladder and, climbing above the white stone, above the powerful and vulgar pose of hand on hip, are crowning the heroic city with branches, bouquets, flags, and republican tinsel. Down below a man in a black hat bends over in front of the gate, which is green with crowns of immortelles which have cockades stuck in them· he seems to be signing a register.

At the entrance to the Rue de Rivoli huge carts overtake me; they are carrying the four quarters of big dead steers lying on their backs covered with green serge.

The main path in the Tuileries Garden is spread with straw. On the bed of this gigantic stable, as though posing for those studies beIoved of Géricault, there rise up and stretch out to the caress of the open air the white, chestnut, or dappled croups of thousands of horses. Behind then the severe line of caissons, each with its spare wheel; and farther than the eye can see under the trees, in the play of light and shadow, more horses' croups, smoke from field forges, mountains of hay and straw. What a grand, exciting spectacle this image of war is, spread out in this pleasure garden among the flowers, the orange trees, and the marble statues, on the pedestals of which sabers and issue overcoats are hung today.

This evening what insouciance, what a fine unconsciousness of the morrow, when the city may be put to fire and slaughter! The same gaiety, the same futility of words, the same light and ironic hum of conversation in restaurants and cafes. Women and men are the same frivolous beings they were before the invasion, except for a few women who are petulant because their husbands spend too long reading the paper. . .

At night I go back along the Tuilleries and see the day's spectacle once more, now bathed in the milky light of the moon which has risen at the end of the Rue de Rivoli, its outline broken by the tall chimney on the Flora Pavilion. Under the electric brightness which makes the green foliage a glassy blue, through the trees which look like trees in mythology, in the silence of the sleeping park where you hear only the ballad of a wakeful artilleryman, all those croups in their white immobility make you think of stone horses, of a marble stud farm, taken from a Parthenon found in an ancient sacred wood.

Monday , September 12

Not only have our officers been incompetent, our soldiers have been craven. In support of what I say I have a letter from my cousin Philippe de Courmont, who was taken prisoer at Sedan, affirming that the soldiers absolutely would not fight. Can it be that the civilian population is going to show he qualities that the army lacked? If that happened, the army would be forever finished in France and we would enter the revolutionary cycle under full steam