The Franco-Prussian War and the Fall of the Second Empire

From Gordon Wright, France in Modern Times: From the Enlightenment to the Present (New York: W.W. Norton, 1981), pp.152-154.

What doomed the empire was not its internal evolution but rather the cumulative results of a series of errors in foreign policy. By 1870 France found itself isolated and  confronted by a powerful new rival across the Rhine. Napoleon III had failed to intervene in central Europe in 1861 when it might have been easy to check the growth of Prussian power. He had failed in his subsequent efforts to secure face-saving compensations in the form of territorial gains along the Rhine. He had failed once more when he sought to bolster French military power by introducing a new army bill into parliament in 1867. His proposal, which would have brought a larger annual contingent of draftees into the army and would have increased the cost of preparedness, aroused a political storm; in the end the bill had to be so watered down that it became innocuous. Meanwhile the failure of Napoleon's "great idea" -- the building of a Catholic empire in Mexico allied with France -- had divided the nation and provided his critics with effective ammunition. Efforts after 1866 to negotiate alliances with Italy and Austria-Hungary produced no result except to arouse false hopes in Paris. War with Prussia was not the only possible outcome of the crisis that erupted suddenly in July, 1870. Either Bismarck or Napoleon III could have averted a test of arms. Bismarck had no desire to avert it; Napoleon lacked the foresight to do so. Chronic illness during the last years of his reign probably lessened his capacity to devote sustained attention to the developing crisis or to make difficult decisions; he was unwise enough to let authority slip into the hands of his second-rate foreign minister, the Duc de Gramont. The French government, aroused at the news that Spain had secretly arranged to place a Hohenzollern [the ruling state in the German nation of Prussia] prince on the Spanish throne, put such heavy pressure on the king of Prussia that the latter persuaded the Hohenzollern nominee to withdraw his candidacy. Gramont had thus won a notable diplomatic victory, but he was not intelligent enough to be satisfied with it. Instead, he demanded still further Prussian assurances for the future, and thus gave Bismarck an opportunity to play the picador to "the Gallic bull." On July 19 the French government, angered at Prussia's apparent flouting of French demands, slipped into war -- unnecessarily, unwisely, and with inadequate preparation for so severe a test.

confronted by a powerful new rival across the Rhine. Napoleon III had failed to intervene in central Europe in 1861 when it might have been easy to check the growth of Prussian power. He had failed in his subsequent efforts to secure face-saving compensations in the form of territorial gains along the Rhine. He had failed once more when he sought to bolster French military power by introducing a new army bill into parliament in 1867. His proposal, which would have brought a larger annual contingent of draftees into the army and would have increased the cost of preparedness, aroused a political storm; in the end the bill had to be so watered down that it became innocuous. Meanwhile the failure of Napoleon's "great idea" -- the building of a Catholic empire in Mexico allied with France -- had divided the nation and provided his critics with effective ammunition. Efforts after 1866 to negotiate alliances with Italy and Austria-Hungary produced no result except to arouse false hopes in Paris. War with Prussia was not the only possible outcome of the crisis that erupted suddenly in July, 1870. Either Bismarck or Napoleon III could have averted a test of arms. Bismarck had no desire to avert it; Napoleon lacked the foresight to do so. Chronic illness during the last years of his reign probably lessened his capacity to devote sustained attention to the developing crisis or to make difficult decisions; he was unwise enough to let authority slip into the hands of his second-rate foreign minister, the Duc de Gramont. The French government, aroused at the news that Spain had secretly arranged to place a Hohenzollern [the ruling state in the German nation of Prussia] prince on the Spanish throne, put such heavy pressure on the king of Prussia that the latter persuaded the Hohenzollern nominee to withdraw his candidacy. Gramont had thus won a notable diplomatic victory, but he was not intelligent enough to be satisfied with it. Instead, he demanded still further Prussian assurances for the future, and thus gave Bismarck an opportunity to play the picador to "the Gallic bull." On July 19 the French government, angered at Prussia's apparent flouting of French demands, slipped into war -- unnecessarily, unwisely, and with inadequate preparation for so severe a test.

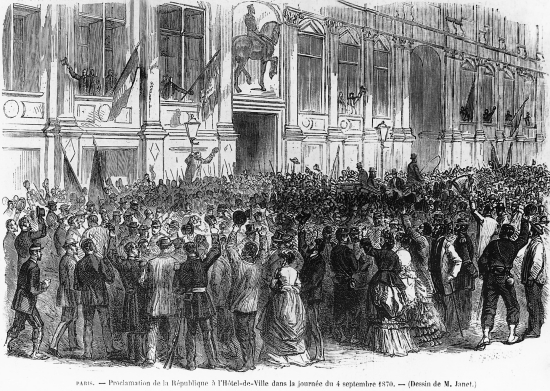

Proclamation of the End of the Second Empire and the Beginning of the Third Republic, Paris, September 4, 1870 |

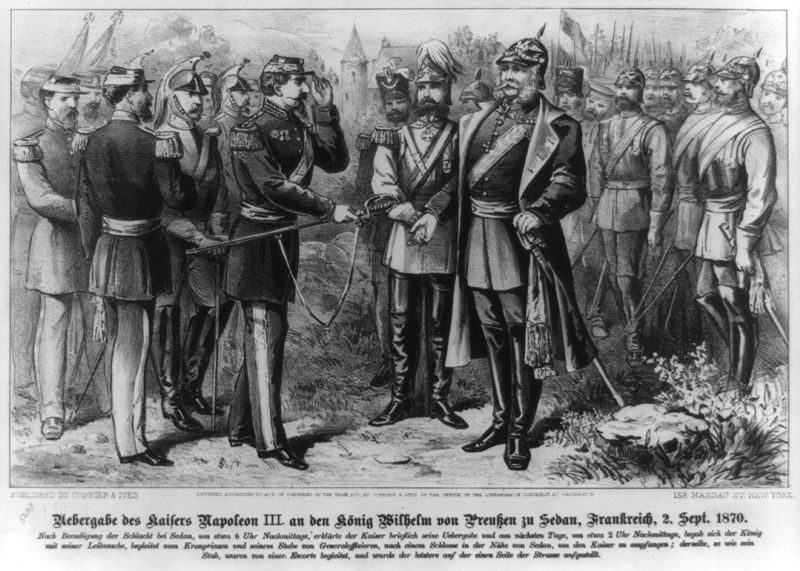

Few Frenchmen except Adolphe Thiers (who had been issuing gloomy warnings ever since 1866) fully understood the threat that France faced. Prime Minister Ollivier encouraged the nation's illusions by announcing that he accepted war "with a light heart," and his war minister even more recklessly assured parliament that the army was ready "to the last gaiter button." What the army lacked in 1870 was not gaiter buttons but something far more serious: efficient, vigorous, and imaginative leadership. The officer corps, though honorable and loyal, had slipped into a rut of routine-mindedness and smug complacency that contrasted sharply with the tough and keen mentality of the Prussian staff. France's clumsy and antiquated process of mobilization had not even b en completed when the first German troops crossed the frontier. Within a month the great border fortress of Metz was cut off by the invaders, and the army of Marshal Bazaine besieged therein. Napoleon, who had gone to the front to share the perils of war with his soldiers, refused to adopt the one strategic plan that might still have averted defeat -- a slow retreat to Paris and a stand outside the walls of the capital. Fearing the political repercussions of such a strategic withdrawal, he accompanied his remaining army under MacMahon in an attempt relieve Metz. The Prussians cornered MacMahon's force at Sedan on August 31 and broke its resistance in a brief battle fought the next day. Napoleon, aware that the fight was hopeless, sought a hero's death in the front lines on the theory that his martyrdom might save the throne for his adolescent son. Even that consolation was denied him; and he fell ignominiously into the hands of the Prussians.

The emperor, but not the empire, survived Sedan. When the news reached Paris on September 3, the regime's political leaders tried desperately to prop up the imperial system by arranging an interim government under a military leader. Even the republican politicians were willing; most of them were not eager to take power at so gloomy a moment. But it was far too late to save the empire; its prestige had vanished in defeat. On September 4 demonstrating crowds converged on the Corps législatif and demanded the proclamation of a republic. Napoleon's system disintegrated without bloodshed, and almost without regret.