Changes in Social Context of Art in France

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp.76-79.

Many alternative institutional systems could have been the endpoint of change in the late nineteenth-century French art world. As it happened, the Impressionist

"movement" became a dramatic focus and exemplification of change . . .

We approach with caution the topic of links between changes in the art world and broad changes in French society. In our opinion, too much with too little basis has been written in this vein. It is difficult enough to identify changes in the specific institutional system within which painters worked, to trace their inter connections and to form some crude estimate of their effects on painting.

written in this vein. It is difficult enough to identify changes in the specific institutional system within which painters worked, to trace their inter connections and to form some crude estimate of their effects on painting.

Least ambiguous of the broader changes was the emergence of France -- that is, of Paris -- as the world cultural center. In painting some evidence of the change was clear:

1. Concentration of dealers with an international clientele.

2. International scope in recruitment of art students.

3. Higher prices of contemporary French painting, as compared to the contemporary painting of other countries.

4. Dominance of France in forming the language and criteria of art journalism.

What are the implications of such international dominance? It was important, as we shall see, to the emergence of the dealer-critic system. Without the conditions just mentioned, the new movements in art appearing on the fringes of the Academic system probably could not have survived the denials of their validity by system.

It is said that the nineteenth century witnessed the rise of the bourgeoisie to material and cultural predominance within France. If so, the revolutionary era around 1848 was crucial. Wealth and governmental power had been concentrated in the hands of an elite which combined resuscitated, prerevolutionary aristocratic lines and the new men who had risen during the early years of the century. Then came bad harvests and the migration to cities of a pool of labor too large for slowly growing industries, which were hampered by tight money. This led to an explosion in favor of electoral oral reform, led by middle-class elements. After Napoleon III restored confidence through a new government open to new men, the economy boomed in a social framework more open for middle-class initiative. Railroad construction, new exports, colonial investment, effects of the Suez Canal project and of California gold reflected and stimulated the boom. . . .

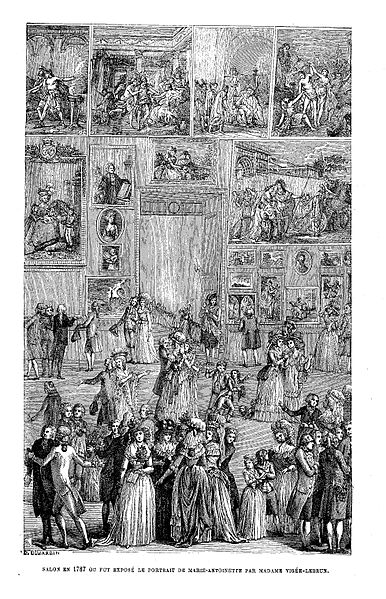

Crucial questions, for our purposes, are whether any such internal social changes may have led to fundamental changes in taste of government or private buyers. The evidence for such fundamental changes is not convincing. In the eighteenth century too the government fostered grandeur and Academic purity in its public and official art. The private buyer, more often than not a wealthy bourgeois, inclined toward genre and landscape and yet bowed to the Academic accreditation of his painters.

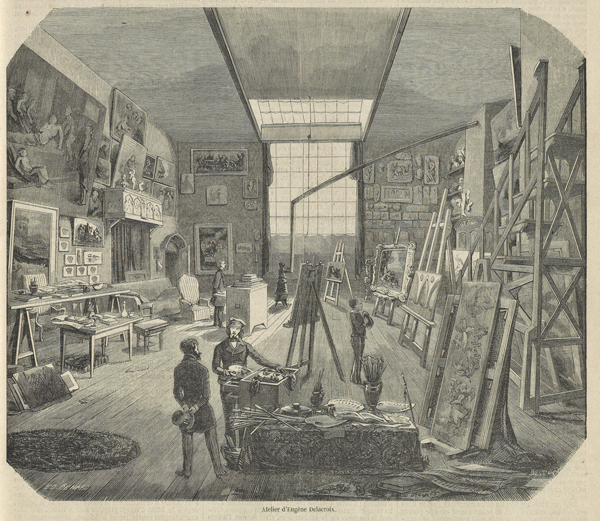

The Studio of Eugène Delacroix. Engraving from: L'Illustration, 25 September 1852 |

Unquestionably, the growth in wealth and size of the middle class created a larger internal market for paintings in France in the nineteenth century, particularly during the Second Empire. Probably there were fewer great collector-connoisseurs, able and willing to subsidize painters. In spite of extensive programs for the decoration of civic buildings in Paris and the provinces, there was less work of decoration on the grand scale as by Lebrun two centuries before, and fewer commissions than during Revolutionary and Napoleonic times. But more art was sold. We quote from the prospectus of a weekly art journal of midcentury, the Moniteur des Arts:

The taste for objects of art grows continually .. . one should not be surprised, then, at the immense development, in recent years, of public sales and art commerce. Paris, much more than London, is considered the price-regulator . .. However ... this other Bourse, the Hotel Drouot [an auction house for art], where, annually, more than twenty million francs changes hands, is but a stepchild of investments and railroads when it comes to publicity.

A lower social and economic level became interested in serious art at the same time that the market in private sales to the well-to do increased. . . .

In the nineteenth century a widespread practice grew up of renting paintings by the night or week. Most of the small merchants involved -- stationers, antique dealers, canvas and color dealers -- found that renting pictures could be their major source of profit. Whether as backdrop for the social occasion in the customer's home or for copying by young ladies in "How to paint in six lessons" courses, rented paintings were in great demand.