Individual Careers and the New System

Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), pp.98-99.

It was artists, not paintings, who were the focus of the dealer critic institutional system. The new system triumphed in part because it could

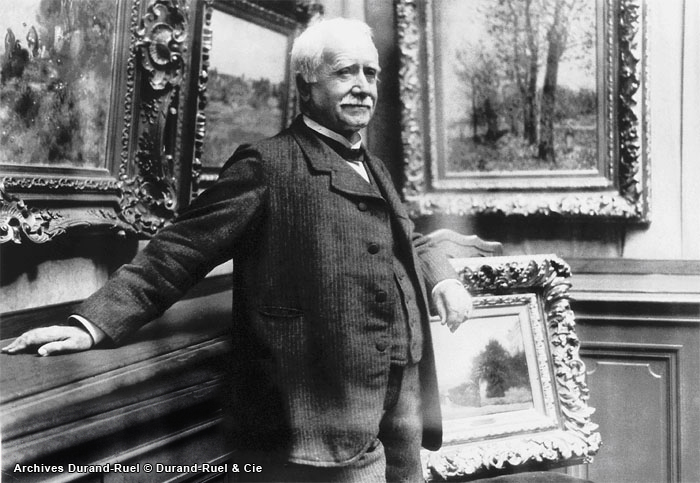

Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922)Durand-Ruel was a prominent art dealer who played a crucial role in making Impressionism a major force in French culture |

and did command a bigger market than the academic-governmental structure. Equally important, however, it dealt with an artist more in terms of his production over a career and thus provided a rational alternative to the chaos of the academic focus on paintings by themselves.

Dealers and critics were not selfless in their relations with artists. Rather, their own interests required them to look at artists more than at individual paintings. A current painting as an isolated item in trade is simply too fugitive to focus a publicity system upon. One does not buy a copy of a recognized painting; the next best thing for inspiring the warmth of confidence in the breast of the shrewd but nervous buyer is a younger sibling of the recognized painting. Independent merit of a painting in and of itself was a principle directly hostile to the institutional imperatives of the dealer-critic system, and to the social and financial needs of the artist.

Good prices for individual paintings did not satisfy a painter if they were realized at erratically spaced times. Committed to a middle-class way of life by the whole ethos of the Academic system, he wanted above all a predictable income, the hallmark of the middle-class concept of a career. This was the carrot Durand Ruel wielded with such success that other dealers followed. In the 1600's Hermann Becker in the Netherlands had developed the same scheme of buying the output of painters -- among them, Rembrandt -- for what amounted to a salary. The need was not idiosyncratic to nineteenth-century French artists. From all points of view then it was the career of an artist that had to be the focus of the system.

Speculation became an important ingredient of the new system. Famous paintings of past centuries had long been recognized a safe investment with growth potential, suitable for international exchange. But changes in value were usually too slow to warrant the term "speculation." In any case, the dealers and buyers for such paintings operated at a higher financial and social level than most buyers of contemporary paintings. Initial prices for current Academic favorites were also so high that they could hardly be looked to for large windfalls.

The new dealer-critic system had a built-in motive for encour aging innovative work: tapping the fever for speculation which possessed much of the nineteenth-century French middle class. The financial speculation in art found its cultural counterpart in the speculation in taste. As critics and dealers were wont to say to the "discerning buyer": "In twenty years he will be considered a master -- and his painting will be worth a fortune!"

But speculation is doubly dangerous when the supply of objects is elastic. Monopoly of an artist's production was important in making speculation rational; Durand-Ruel in his first daring coup bought up almost the entire production of several Barbizon painters. The speculative motive reinforced the concern of the dealer with the total career of the painter.