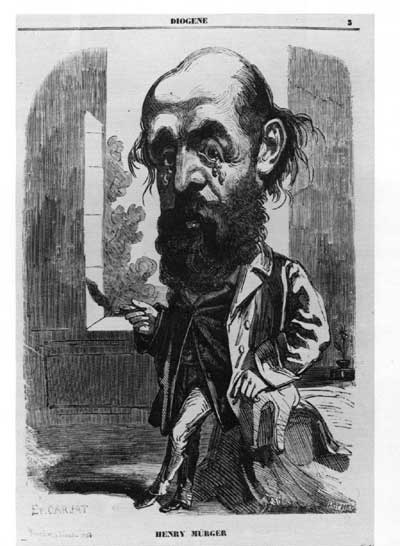

Henri Murger, "Preface" to Bohemians of the Latin Quarter

In this preface to his sketches on the artistic and intellectual Bohemians of Paris Murger presents the kind of romantic vision of the artist that lured many French youths away from the bourgeois world of their parents into the counter-culture of the Left Bank. In a world that glorified art and the artist it was easy for young people in France to imagine that they would be the great cultural heroes of their generation. This body of young artists and intellectuals encouraged one another to break the rules of the official culture of the Academies and to develop their own notions of art, and this gave many of them the strength that they needed to defy their elders and develop new visions of art.

The Bohemians of whom it is a question in this book have no connection with the Bohemians whom melodramatists have rendered synonymous with robbers and  assassins. Neither are they recruited from among the dancing-bear leaders, sword swallowers, gilt watch-guard vendors, street lottery keepers and a thousand other vague and mysterious professionals whose main business is to have no business at all, and who are always ready to turn their hands to anything except good.

assassins. Neither are they recruited from among the dancing-bear leaders, sword swallowers, gilt watch-guard vendors, street lottery keepers and a thousand other vague and mysterious professionals whose main business is to have no business at all, and who are always ready to turn their hands to anything except good.

The class of Bohemians referred to in this book are not a race of today, they have existed in all climes and ages, and can claim an illustrious descent. In ancient Greece, to go no farther back in this genealogy, there existed a celebrated Bohemian, who lived from hand to mouth round the fertile country of Ionia, eating the bread of charity, and halting in the evening to tune beside some hospitable hearth the harmonious lyre that had sung the loves of Helen and the fall of Troy. Descending the steps of time modern Bohemia finds ancestors at every artistic and literary epoch. In the Middle Ages it perpetuates the Homeric tradition with its minstrels and ballad makers, the children of the gay science, all the melodious vagabonds of Touraine, all the errant songsters who, with the beggar's wallet and the trouvere's harp slung at their backs, traversed, singing as they went, the plains of the beautiful land where the eglantine of Clemence Isaure flourished. . .

We will add that Bohemia only exists and is only possible in Paris.

We will begin with unknown Bohemians, the largest class. It is made up of the great family of poor artists, fatally condemned to the law of incognito, because they cannot or do not know how to obtain a scrap of publicity, to attest their existence in art, and by showing what they are already prove what they may some day become. They are the race of obstinate dreamers for whom art has remained a faith and not a profession; enthusiastic folk of strong convictions, whom the sight of a masterpiece is enough to throw into a fever, and whose loyal heart beats high in presence of all that is beautiful, without asking the name of the master and the school. This Bohemian is recruited from amongst those young fellows of whom it is said that they give great hopes, and from amongst those who realize the hopes given, but who, from carelessness, timidity, or ignorance of practical life, imagine that everything is done that can be when the work is completed, and wait for public admiration and fortune to break in on them by escalade and burglary. They live, so to say, on the outskirts of life, in isolation and inertia. Petrified in art, they accept to the very letter the symbolism of the academical dithyrambic, which places an aureola about the heads of poets, and, persuaded that they are gleaming in their obscurity, wait for others to come and seek them out. We used to know a small school composed of men of this type, so strange, that one finds it hard to believe in their existence; they styled themselves the disciples of art for art's sake. According to these simpletons, art for art's sake consisted of deifying one another, in abstaining from helping chance, who did not even know their address, and in waiting for pedestals to come of their own accord and place themselves under them.

It is, as one sees, the ridiculousness of stoicism. Well, then we again affirm, there exist in the heart of unknown Bohemia, similar beings whose poverty excites a sympathetic pity which common sense obliges you to go back on, for if you quietly remark to them that we live in the nineteenth century, that the five-franc piece is the empress of humanity, and that boots do not drop already blacked from heaven, they turn their backs on you and call you a tradesman.

For the rest, they are logical in their mad heroism, they utter neither cries nor complainings, and passively undergo the obscure and rigorous fate they make for themselves. They die for the most part, decimated by that disease to which science does not dare give its real name, want. If they would, however, many could escape from this fatal denouement which suddenly terminates their life at an age when ordinary life is only beginning. It would suffice for that for them to make a few concessions to the stern laws of necessity; for them to know how to duplicate their being, to have within themselves two natures, the poet ever dreaming on the lofty summits where the choir of inspired voices are warbling, and the man, worker-out of his life, able to knead his daily bread, but this duality which almost always exists among strongly tempered natures, of whom it is one of the distinctive characteristics, is not met with amongst the greater number of these young fellows, whom pride, a bastard pride, has rendered invulnerable to all the advice of reason. Thus they die young, leaving sometimes behind them a work which the world admires later on and which it would no doubt have applauded sooner if it had not remained invisible.

In artistic struggles it is almost the same as in war, the whole of the glory acquired falls to the leaders; the army shares as its reward the few lines in a dispatch. As to the soldiers struck down in battle, they are buried where they fall, and one epitaph serves for twenty thousand dead.

So, too, the crowd, which always has its eyes fixed on the rising sun, never lowers its glance towards that underground world where the obscure workers are struggling; their existence finishes unknown and without sometimes even having had the consolation of smiling at an accomplished task, they depart from this life, enwrapped in a shroud of indifference. . . .

We now come to the real Bohemia, to that which forms, in part, the subject of this book. Those who compose it are really amongst those called by art, and have the chance of being also amongst its elect. This Bohemia, like the others, bristles with perils, two abysses flank it on either side—poverty and doubt. But between these two gulfs there is at least a road leading to a goal which the Bohemians can see with their eyes, pending the time when they shall touch it with their hand. . . .

To arrive at their goal, which is a settled one, all roads serve, and the Bohemians know how to profit by even the accidents of the route. Rain or dust, cloud or sunshine, nothing checks these bold adventurers, whose sins are backed by virtue. Their mind is kept ever on the alert by their ambition, which sounds a charge in front and urges them to the assault of the future; incessantly at war with necessity, their invention always marching with lighted match blows up the obstacle almost before it incommodes them. Their daily existence is a work of genius, a daily problem which they always succeed in solving by the aid of audacious mathematics. They would have forced Harpagon to lend them money, and have found truffles on the raft of the "Medusa." At need, too, they know how to practice abstinence with all the virtue of an anchorite, but if a slice of fortune falls into their hands you will see them at once mounted on the most ruinous fancies, loving the youngest and prettiest, drinking the oldest and best, and never finding sufficient windows to throw their money out of. Then, when their last crown is dead and buried, they begin to dine again at that table spread by chance, at which their place is always laid, and, preceded by a pack of tricks, go poaching on all the callings that have any connection with art, hunting from morn till night that wild beast called a five-franc piece.

The Bohemians know everything and go everywhere, according as they have patent leather pumps or burst boots. They are to be met one day leaning against the mantel-shelf in a fashionable drawing room, and the next seated in the arbor of some suburban dancing place. They cannot take ten steps on the Boulevard without meeting a friend, and thirty, no matter where, without encountering a creditor.

Bohemians speak amongst themselves a special language borrowed from the conversation of the studios, the jargon of behind the scenes, and the discussions of the editor's room. All the eclecticisms of style are met with in this unheard of idiom, in which apocalyptic phrases jostle cock and bull stories, in which the rusticity of a popular saying is wedded to extravagant periods from the same mold in which Cyrano de Bergerac cast his tirades; in which the paradox, that spoilt child of modern literature, treats reason as the pantaloon is treated in a pantomime; in which irony has the intensity of the strongest acids and the skill of those marksmen who can hit the bull's-eye blindfold; a slang intelligent, though unintelligible to those who have not its key, and the audacity of which surpasses that of the freest tongues. This Bohemian vocabulary is the hell of rhetoric and the paradise of neologism.

Such is in brief that Bohemian life, badly known to the puritans of society, decried by the puritans of art, insulted by all the timorous and jealous mediocrities who cannot find enough of outcries, lies, and calumnies to drown the voices and the names of those who arrive through the vestibule to renown by harnessing audacity to their talent.

A life of patience, of courage, in which one cannot fight unless clad in a strong armour of indifference impervious to the attacks of fools and the envious, in which one must not, if one would not stumble on the road, quit for a single moment that pride in oneself which serves as a leaning staff; a charming and a terrible life, which has conquerors and its martyrs, and on which one should not enter save in resigning oneself in advance to submit to the pitiless law væ victis.

H. M.