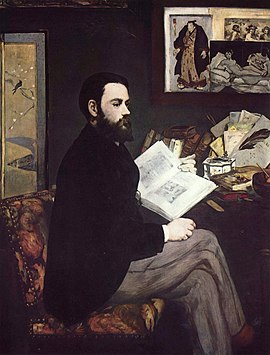

Émile Zola, whom we will encounter many times in this course, was one of the most prominent French novelists of the second half of the 19tyh century, As the most prominent exponent of naturalism in literature, he felt a comradship with the Impressionisrs, whose efforts to capture in painting the exterior world as it actually appeared to them he saw as parallel to his own form of writing. Blow is part of a newspaper article in which he defends the Impressionists against attacks from conservative critics.

|

These last few years something very interesting and instructive has been happening under our own

This

is, then, what the Impressionist painters have to offer: a more

exact examination of the causes and effects of light, exerting

its influence both on color and design. They have been

justifiably accused of drawing their inspiration from Japanese

prints.... It is certain that our dark schools of painting, the

bituminous-minded work of our established schools, has been

surprised and forced to rethink things when faced with the

limpid horizons, the beautiful vibrant spots of the Japanese

water-colorists. There was in these works a simplicity of means

and an intensity of performance which struck our young artists

and drove them on to this path of painting soaked in air and

light a path which all the talented newcomers take today. . . . The great

pity is that this new formula which they all bring scattered in

their works, not one of the artists of the group has realized it

powerfully and definitively. The formula is there, endlessly

divided; but nowhere, in any one of them, do we find it applied

by a master. ...

Yet, while we can take objection to their personal

incapacity, they remain none the less the true representatives

of our time. They have plenty of gaps, their workmanship is too

often slack, they are too easily satisfied, they show themselves

to be incomplete, illogical, exaggerated, ineffectual. No

matter: it is enough for them to apply themselves to

contemporary naturalism in order to find themselves at the head

of a movement and play a great part in our school of painting. |