F.W.J. Hemmings, “The Art World: Producers and Consumers” from Culture and Society in France, 1789-1848 (Leicester University Press, 1987), pp.173-176.

Claude Monet, Luncheon on the Grass (1865-1866) |

It was in part the desperate poverty dogging these painters [the Impressionists] that drove them to the unusual expedient of doing much of their work entirely in the open, summer and winter alike. To rent a studio in Paris was expensive; so, while Manet, Degas, and Bazille continued to produce indoor painting, the others were driven by the force of circumstances out of Paris into the country. Pissarro, of course, had been painting landscapes since before the younger members of the group had started their careers; it was a landscape of his that was accepted for exhibition in the 1859 salon. Monet had practised the art, under the supervision first of Boudin, later of Jongkind, at Le Havre, and it was he who persuaded the friends he had made at Gleyre's studio to accompany him to Chailly, on the edge of the Forest of Fontinebleau, in the spring of 1864. Neither Renoir, Sisley, nor Bazille had had any experience of this kind of work, and it was Monet who initiated them. It is true that they had before them the example of the Barbizon school of landscape painters, who had been working in different parts of the forest for a generation. But there was one significant difference between their method and that which Monet favoured and encouraged his friends to follow. The older painters relied partly at least on their memory; they would sketch a picture out of doors, or take notes, but it would be finished in the studio. Millet went so far as to paint entirely from memory after mentally photographing the scene that he wished to reproduce. Only Daubigny, who was not at that period working at Barbizon, painted his landscapes directly from nature, without troubling to give them the finishing touch in the studio. Precisely for that reason they looked 'unfinished' to the ordinary academic critic, and Gautier, for example, complained petulantly: 'It is really too bad that this landscape painter . . . should be satisfied with an impression, and should neglect details to the extent he does. His pictures are no more than rough drafts, left in a very unfinished state.' There was no one to point out to Gautier that an impression cannot be rendered otherwise than by a picture that looks unfinished, since the 'finished' look destroyed the spontaneity and delicate freshness of the appearance. But even if some apologist had come up with this explanation, it is unlikely that the critic would have changed his mind: to count as art at all, a picture needed, at this time, to look as though it had been carefully worked over, with every detail made clearly recognizable. This was one of the difficulties that Monet and his friends had to contend with, though it made itself felt in a more acute form when they started exhibiting together after the war. . . .

More and more [Monet] was becoming interested in the transformations wrought by sunlight as it played over objects. . . . While [Monet] was painting the large open-air picture, Femmes cueillant des fleursurs (another work rejected in 1867 which is now in the Louvre), Courbet chanced to visit him and asked why he was sitting in front of his canvas doing nothing. Monet explained that he was waiting for the sun to come out from behind a cloud. 'But surely', asked Courbet, 'you could fill in the time doing some work on the background?' Monet had to explain to the disbelieving master that a picture done out of doors could have no unity unless every part of it was painted in the same conditions of light.

Other members of the group were making their own discoveries as they practised open-air painting: Bazille as he worked at Montpellier on the large canvas representing members of his family on the terrace of their house -- a picture exhibited in the 1868 salon -- Renoir with the new portrait of Lise, standing in strong sunshine, her face shaded by a parasol, which was seen in the same exhibition. This picture proves that Renoir had advanced beyond Monet in his analysis of the colours of shadows as they were cast by the thin fabric of the painted parasol on to the young woman's face, neck and shoulders. It was realized that the diffraction of sunlight in the air meant that shadows were never quite black: pure blacks and whites were artificial abstractions, hardly ever encountered in nature. Nor could shadows be truthfully rendered by simply darkening the colour of the object which was in shadow. They were what the painters at last, rubbing their eyes, saw them to be: possessed of different, but complementary colours, often with bluish tints if the sky was clear. The snowscapes undertaken simultaneously by Monet, Pissarro and Sisley in the winter of 1868-9 were essentially experiments to discover what happened when objects cast shadows on the white expanse in strong or weak sunlight.

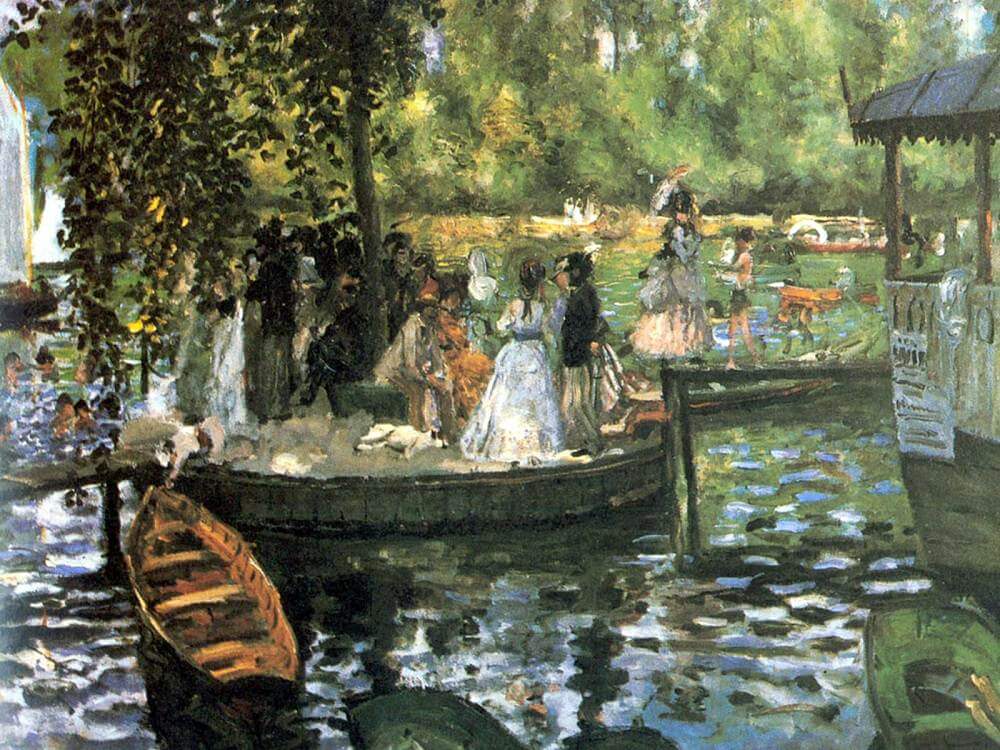

All this, and much else, sprang from the revolutionary step they took when they decided to look at nature with their own eyes and forget -- as Manet found it so difficult to forget -- how all other artists since the Renaissance had seen, or at least shown, such simple things as grass, trees in leaf, the skin on women's arms and faces, the shimmering of wind-blown water. Not only did everything need to be looked at afresh, but the rendering of this new universe demanded a new and different use of tried techniques. The smooth brush-strokes had to be abandoned, since they had originally been developed as a consequence of the superstition, now exploded, that each object had its own particular (so-called local) colour, unaffected by the colours of surrounding objects. Instead, Monet and Renoir, working together at La Grenouillere, discovered the potentialities of the short brush-stroke, the hachure, the blob, the twirl, to represent the broken surfaces of reflections in rippling water and the hazy outlines of animated faces and bodies in motion, of details that the eye glides over and that the retina causes to swim together in a vivid kaleidoscope.

After this fashion was Impressionism born, though it had still not been baptized. In this way did the visible world suddenly become a brighter, more intense and gayer place, or at least so it seems to us who can look back at that moment when the revelation was made.

Pierre Auguste Renoir, La Grenouillère (1869)