Robert Gildea, Children of the Revolution

Realism and Impressionism

Princesse Mathilde's salon was home to the Realist school of writers, but these also had other venues for

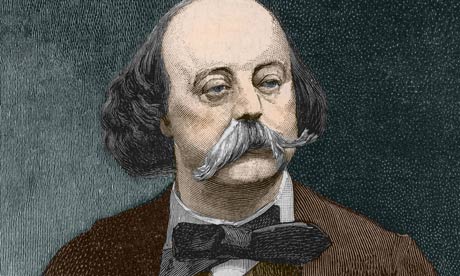

Gustave Flaubert |

meeting. From 1874 Flaubert organized monthly dinners, suceeding those at Magny's restaurant in the 186os, for 'the Five' whose novels may have been successful but whose plays had been shouted down by theatre audiences. 'We were all gourmands,' recalled Alphonse Daudet, 'with as many gourmandises as temperaments and provinces of origin. Flaubert wanted Normandy butter and R0uen ducks, Zola demanded seafood, Edmond de Goncourt ordered ginger delicacies while Turgenev tasted caviar. Ah! We were not easy to feed and the Paris restaurants remembered us. We often had to change the venue.'

After Flaubert's death in I88o the group was kept together by Daudet who held his own salon on a Thursday in the avenue de l'Observatoire, presided over by his wife Julia, while in 1885 Edmond de Goncourt refurbished the loft at Auteuil where his brother Jules had died, done up with Japanese art, and visited with some trepidation by the Princesse Mathilde the following year. Zola bought a villa at Medan on the Seine in 1878 with the royalties from L'Assommoir and held meetings of his own young proteges such as Guy de Maupassant and Joris-Karl Huysmans, son of a Dutch father and French mother. In 1880 they published a collection of short stories, Les Soirées de Médan, which served as a manifesto for the Naturalist school and included Maupassant's Boule de suif, a short story set during the war of 1870 about a prostitute who is persuaded by her bourgeois travelling companions to sleep with a Prussian officer so that the coach can move on, and described by Flaubert as a masterpiece. Naturalism, depicting humanity as determined by hereditary and environmental laws and reduced almost to bestiality, in fact drove a wedge between Zola and his circle on the one hand and Goncourt and Daudet on the other. In I887, after the publication of Zola 's La Terre, an attack on his work's 'indecency and filthy terminology' was published in Le Figaro, which Zola believed to have been inspired by Goncourt and Daudet.

Close links had been established before this break between the Realists and the Impressionists. Both challenged

Édouard Manet, Nana (1877) |

the literary and artistic establishment with their treatment of modern life, warts and all, and were often marginalized by it. Monet and Degas held court in the Cafe Guerbois in the Batignolles district, then in the more refined Cafe de la Nouvelle Athenes, which were also frequented by Zola. Nana, the prostitute who appears in L'Assommoir before having a novel to herself in I88o, was painted by Manet, a picture rejected for the Salon of 1877, while Zola tried to defend Impressionism through his treatment of the struggling artist in L'Oeuvre of 1886. Huysmans was launched as an art critic by Zola, attacking the academic art of the Salon and preaching the virtues of Manet and Degas. 'A painter of modern life is born,' said Huysmans of Degas in 188o, painting the flesh of ballet dancers lit by gaslight or the pale glow from courtyards, completely different from the classical school of Bouguereau's Birth of Venus, a 'badly pumped-up windbag, without muscles, nerves or blood. A single pinprick in the torso and it would collapse. That said, Zola and Huysmans found other Impressionists such as Monet and Pissarro guilty of 'indigomania' and Gauguin argued that Huysmans liked Degas and Manet only because their work was figurative: 'it is naturalism that gratifies him.'

William-Adolphe Bouguereau, The Birth of Venus (1879)