The Impressionists and the Critics

From Orlando Figes, The Europeans: Three Livies and the Making of a Cosmopolitan Culture (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019), pp. 378-381.

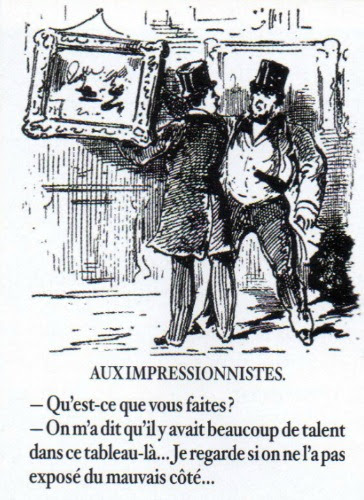

AT THE IMPRESSIONISTS’ SALON - What are you doing? - They told me there was a lot of talent in

this painting...I was looking to see if they weren't showing the

wrong side.

Meanwhile the Impressionists were struggling to sell their work at all. There were many art collectors . . . who shied away from buying them. They were too avant-garde, and not safe investments like the Barbizon painters. The Impressionists were ridiculed at their First Exhibition at Nadar's photographic studio on the boulevard des Capucines in the spring of 1874. "Public opinion against these dangerous innovators was whupped up so intensely [by the press]," recalled [art dealers Jean-Marie] Durand-Ruel, "that visitors arrived with the firm intention of laughing and did not even bother to look." An auction of their works at the Hotel Drouot the next year occasioned such riotous commotion, with people shouting insults at the works, that Charles Pillet, had to call the police to protect the paintings, most of which were sold for trifling sums, many for less than 100 francs. . . At their Second Exhibition, at Durand-Ruel's gallery in April 1876, the Impressionists were scorned again, "There has just been opened at Mr. Durand-Ruel's an exhibition of what is said to be painting," wrote the critic of Le Figaro. "Five or six lunatics, of whom one is a woman, have chosen to exhibit their works. There are people who burst into laughter in front of these objects. Personally I am saddened by them. These so-called artists style themselves Intransigents, Impressionists." Durand-Ruel was berated by the art establishment for backing them. I was treated as a madman and a person of bad faith," he wrote. "Little by little the trust I had succeeded in inspiring disappeared and my best clients began to question me. . . .

The Impressionists explained their failure in

terms of the public's inability to recognize their worth. The scandal of

their first two exhibitions became part of their mythology of

unacknowledged genius (in the twentieth century this idea was central to

their brand. As Monet put it to Durand-Ruel in 1881, "There are scarcely

fifteen amateur collectors in Paris who capable of liking a painting

without the imprimateur of the Salon. There are 80,000 buyers who won't

buy a thing if it has not been in the Salon. . .”

Taste does not develop on its own. It is

shaped by intermediaries -- by influential patrons, critics, dealers and

collectors -- who take the lead in buying and promoting works that are

new and difficult for the establishment and the general public to

accept. Such intermediaries would play the decisive role in changing

attitudes to the Impressionists. The first signs of this change were

discernible in the critical reaction to their Third Exhibition in 1877,

but the real transformation began only in the next decade, when

Durand-Ruel found a market for them in America.

The role of the critic was vitally important in this transformation in artistic tastes. One of the earliest to champion the cause of the Impressionists was Théodore Duret, a friend and promoter of Manet from 1865, who started buying Pissarros and Monets in 1873. Duret did not write a great amount about their works until his booklet Les Peintres impressionistses [The Impressionist Painters], in 1878, but he spent a lot of time persuading friends and contacts to buy them. . . Duret advised Sisley and Pissarro on what subjects would attract buyers, on how much they could ask for their paintings, and sometimes acted as a sales agent . . .

In terms of his influence Zola was the most

important critic to champion the Impressionists in the 1870s. . . Zola

has promoted Manet and his artistic followers as far back as 1863, when

Manet’s paintings, including Le

Déjeuner sur l’herbe [Picnic

on the Grass], had been rejected by

the Salon but famously displayed in the so-called “Salon des Refusés”

(Salon of the Rejected) allowed by Napoleon III. Zola identified with

Manet and the other rejected painters (among them Courbet, Pissarro,

Cézanne, Whistler, and Fantin-Latour) as the pioneers of a truly modern

form of art, breaking free from the conventions of “boudoir

painting” and the conservative establishment of the Academy. He saw them

as allies of his own campaign for a modern literature. “Manet will be

one of the masters of tomorrow,” he wrote in

L’Évènement

in May 1866, “and if I had a fortune, I would do good business by buying

up all his paintings. In fifty years, they will be worth twenty times

the price they reach today, while certain paintings valued now at 40,000

francs won’t then fetch even 400.” . . .