From Orlando Figes, The Europeans: Three Livies and the Making of a Cosmopolitan Culture (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2019), pp.383-385

The place where Zola met the

Impressionists most often was at the salon of his publisher, Georges

Charpentier, a keen early patron of the Impressionists. . . Renoir soon

became a

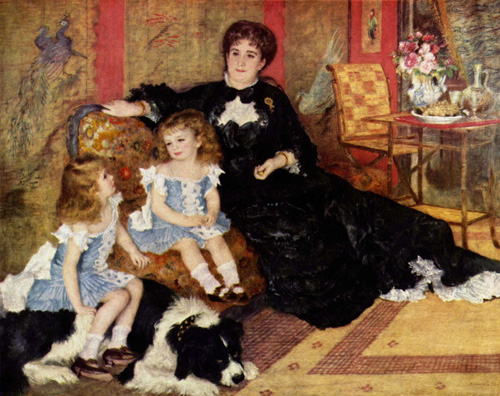

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Madame Chapentier and her Children

(1878)

regular visitor to the Charpentier's house in

the rue de Grenelle, where he painted the celebrated portrait

Madame Georges Charpentiers et ses enfants

(Madame Georges Charpentiers and her

children) . . .Through Renoir the

Charpentiers began to buy from other Impressionist painters, who often

wrote to them for loans against future sales. In 1879, Charpentier

established the weekly journal La Vie

moderne (Modern

Life) to promote their ideas and help

them financially by paying them for articles. At the instigation of his

wife, whose artistic views were often sought by the Impressionists, he

opened a gallery for them in the Passage des Princes, one of the arcades

built by Haussmann, near the boulevard des Italiens. At the first

exhibition, for Manet, in 1880, a free catalogue was given out to

passers-by in the street, but no paintings sold.

Charpentier’s salon was critical in

getting other patrons to invest in the Impressionists. Many of their

earliest collectors were regulars at his salon . . . or part of the

broader Parisian élite that mixed with that crowd. Still, there were no

more than fifty in Paris. Some were friends of the artists, such as the

composer Emmanuel Chabrier, a friend of Manet and Degas, who depicted

him, the only member of the audience to be seen, in his painting

The Orchestra at the Opéra.

Others were artists themselves, notably the Impressionist painter

Gustave Caillebotte, who inherited a private income of 100,000 francs a

year from his father’s business in military supplies. He not only bought

a lot of the Impressionists’ paintings but lent money to them too. Most

of the early buyers, however, were self-made men – manufacturers,

financiers, professionals, who identified with modern art (it showed the

world in which they lived, right-bank Paris in particular). They had

diverse motives for their purchases: to furnish their mansions with

paintings which they liked; to buy art for speculative purposes; and to

make a statement about their status as major patrons of the arts. . . .

More than anybody else, it was Durand-Ruel who

enabled the Impressionists to break into the market. Without him, in all

probability, they would not have become widely known and the history of

modern art would have been completely different. In the early 1870s

Durand-Ruel was the only Paris dealer to back the Impressionists. . .

The basic idea of his business plan (which would become common practice

in the modern dealer system) was to buy a large amount of an artist’s

work and raise the value by promoting it. He was the first of a new

breed of art dealers who changed public taste by stimulating interest in

an unknown brand of art, as opposed to the more established practice of

dealing in those works of art which were already known and in demand.

More than anybody else, it was Durand-Ruel who

enabled the Impressionists to break into the market. Without him, in all

probability, they would not have become widely known and the history of

modern art would have been completely different. In the early 1870s

Durand-Ruel was the only Paris dealer to back the Impressionists. . .

The basic idea of his business plan (which would become common practice

in the modern dealer system) was to buy a large amount of an artist’s

work and raise the value by promoting it. He was the first of a new

breed of art dealers who changed public taste by stimulating interest in

an unknown brand of art, as opposed to the more established practice of

dealing in those works of art which were already known and in demand.

Durand-Ruel bought up works by the

Impressionists wholesale, borrowing from bankers, and, if necessary to

corner the market, entering into partnership with other dealers. . .

As

a long-term investor in their work, Durand-Ruel was as much a patron as

a dealer to the Impressionists. He gave them loans and encouragement

when they most needed them. There were times when he came close to

bankruptcy because their paintings did not sell. To raise their value on

the market Durand-Ruel employed a number of innovative strategies

borrowed from investors on the stock exchange. He pushed up the bidding

for his own artists to increase their perceived worth . . . As he had

done with the Barbizon painters, he founded an art review to promote the

Impressionists. He specialized in one-man shows, a practice that became

more common from the 1880s as other dealers learned from his success,

and, instead of hanging paintings in the crowded manner usual at the

time, gave each picture lots of space to emphasize its importance. He

campaigned hard to get their works into public galleries and museums,

recognizing these as “our best publicity”. He loaned their works to

international exhibitions, and built links with agencies and dealers to

develop foreign sales. The art market was internationalized at an ever

growing rate from the 1870s, as cheaper photographic reproductions, the

telegraph and a faster postal system enabled information about new

paintings to cross national frontiers more easily. Durand-Ruel was one

of the first dealers to exploit fully these developments with agencies

in Europe and America. It was in the United States and Russia that

through him the Impressionists would find their biggest markets in the

last two decades of the century.