The Café

His

[Zola's] life

shifted

increasingly

toward the

Right Bank

now that

he saw

more and

more painters

who

inhabited

Les Batignolles.

Linked to

central Paris by

omnibuses called

"Batignollaises," this

urban village,

where

cottages

survived among

recently built

tenements, became

home for

people needing

cheap digs

or wanting

asylum from

revolutionary turmoil.

Its population

had swelled

after 1848

and continued

to

swell

under

Napoleon III,

when widespread

demolition of

slums cast

thousands

adrift.

Pensioned

civil

servants,

retired

shopkeepers,

downat-heel

spinsters,

and

unemployed workers

made do

in an

environment that

also proved

hospitable to

young

artists.

Manet lived

on the

rue de

Saint-Petersbourg (later

renamed Leningrad);

within hailing

distance

of

him

were

Bazille,

Sisley, Renoir,

and

Degas.In

1867, Zola,

too, found

quarters in

Les Batignolles.

Meanwhile he

showed up

almost

every

week

at

a

cafe

just

off the

Place de

Clichy

where

he

was

sure

to

find his

painter friends

assembled,

especially

on Friday

afternoons, when

they met

in plenary

session, knowing

that

Manet

would

join

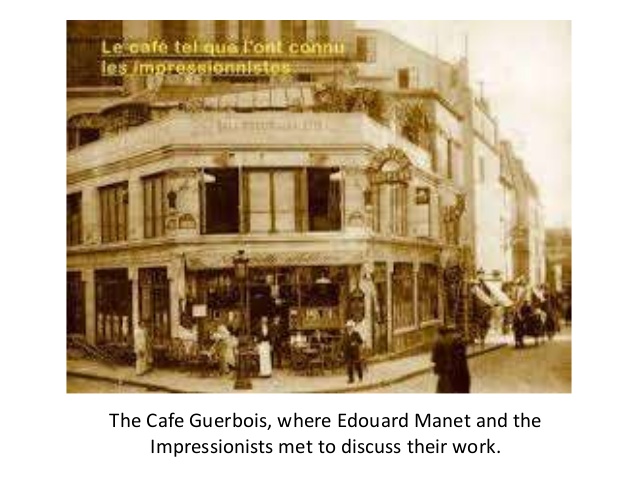

them. Until

Manet

"discovered"

it,

nothing distinguished

the

Cafe Guerbois

except its

trellised

garden.

Most habitues

came for

sport, and

billiard balls

colliding on

tables in

a dimly

lit back

room echoed

through the

saloon, which

had mirrors

and gingerbread

to remind

Manet of

his beloved

Boulevard. Here

he matched

wits with Degas

while

neighborhood

folk,

perplexed

by

their

conversation,

looked sideways

at what

they called

"the artists'

comer."

It

was

a lively

scene, if

not

bohemian

in

the

way

that

the

Cafe

Momus

had

been

when Charles

Baudelaire,

Gustave

Courbet,

and

Gerard

de

Nerval

gathered there

during the

1840s.

As Monet

remembered

years

later:

His

[Zola's] life

shifted

increasingly

toward the

Right Bank

now that

he saw

more and

more painters

who

inhabited

Les Batignolles.

Linked to

central Paris by

omnibuses called

"Batignollaises," this

urban village,

where

cottages

survived among

recently built

tenements, became

home for

people needing

cheap digs

or wanting

asylum from

revolutionary turmoil.

Its population

had swelled

after 1848

and continued

to

swell

under

Napoleon III,

when widespread

demolition of

slums cast

thousands

adrift.

Pensioned

civil

servants,

retired

shopkeepers,

downat-heel

spinsters,

and

unemployed workers

made do

in an

environment that

also proved

hospitable to

young

artists.

Manet lived

on the

rue de

Saint-Petersbourg (later

renamed Leningrad);

within hailing

distance

of

him

were

Bazille,

Sisley, Renoir,

and

Degas.In

1867, Zola,

too, found

quarters in

Les Batignolles.

Meanwhile he

showed up

almost

every

week

at

a

cafe

just

off the

Place de

Clichy

where

he

was

sure

to

find his

painter friends

assembled,

especially

on Friday

afternoons, when

they met

in plenary

session, knowing

that

Manet

would

join

them. Until

Manet

"discovered"

it,

nothing distinguished

the

Cafe Guerbois

except its

trellised

garden.

Most habitues

came for

sport, and

billiard balls

colliding on

tables in

a dimly

lit back

room echoed

through the

saloon, which

had mirrors

and gingerbread

to remind

Manet of

his beloved

Boulevard. Here

he matched

wits with Degas

while

neighborhood

folk,

perplexed

by

their

conversation,

looked sideways

at what

they called

"the artists'

comer."

It

was

a lively

scene, if

not

bohemian

in

the

way

that

the

Cafe

Momus

had

been

when Charles

Baudelaire,

Gustave

Courbet,

and

Gerard

de

Nerval

gathered there

during the

1840s.

As Monet

remembered

years

later:

Edouard Manet, The Café |