The Successful Artist

From Raymond Rudorff, The belle epoque; Paris in the nineties (New York, Saturday Review Press, 1973)

Most of the critics, the public and buyers generally agreed that French art had reached an ideal state and was destined to continue as before, with each new generation of artists faithfully adhering to established styles and standards. Art was a system and, for those who conformed to the system and became popular, the rewards were great. Once a painter was weil established, he led a comfortable life. The most successful artists lived like princes in great mansions in the most fashionable parts of Paris, magazines published photographs of them in their huge studios, they were welcome in high social circles and were given important commissions and honours by members of the government and civil service. They virtually monopolised the art market, dominated the exhibitions and became members of juries at the Salon. No matter what they painted, the successful painters all shared a common feeling that they belonged to the same caste. An academic or Salon painter was a member of a club with clearly defined and unchangeable rules. They were public figures and established, officially approved representatives of their nation's culture.

There was no question of the artist

being a man outside society, a rebel shut away in his studio

struggling to express a personal emotion or view of life in an

idiosyncratic manner which disregarded the way other artists painted and

the methods by which art was taught. They were at peace with a

society which they served and which honoured them in return, and they

earned vast sums.

The academics had learned how to paint in a certain manner and -- perhaps even more important -- they knew exactly what they were expected to paint. The idea that an artist could change his style and technique, mature and transform his art as he followed the impulsions of his genius was alien to them. Similarly, the idea that the officially accepted attitude to art could be stultifying, outmoded or reactionary never occurred to most artists and critics. They would have been deeply hurt if anyone had called them either reactionary or unimaginative. . .

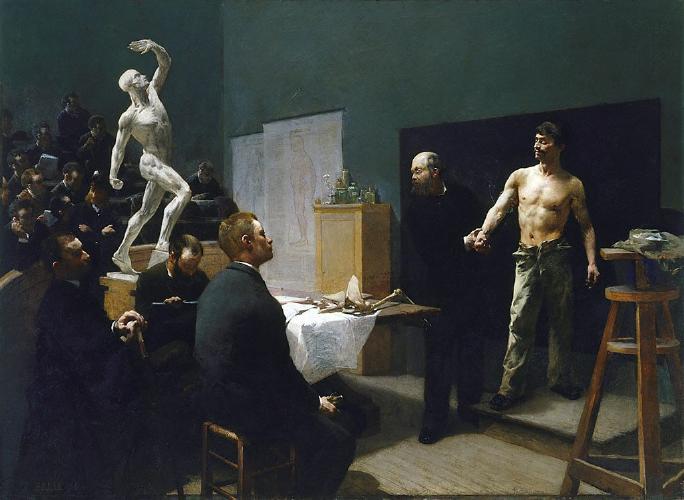

If a newcomer wished to enter the privileged circle of painters who earned fortunes and were awarded official honours, he would have to conform to the system which had been established. He would have to learn a conventional idea of artistic beauty which was taught in the art schools "as one teaches algebra," as the architect Viollet-le-Duc once remarked.

François Sallé (France, 1839-1899) The anatomy class at the Ecole des Beaux Arts (1888)