Charles Sowerwine, “The Social and Cultural Bases of Republicanism” in France since 1870: Culture, Politics, and Society (1)

Reason and the republican project

The triumph of the Third Republic ended a struggle begun in the 'French Revolution of 1789. That struggle can be called the republican project. It depended on the assumption that human beings could use Reason to change their world. Otherwise they would have had no right to change the monarchy, which was ordained by God. To use Reason to change the world, the universe had to be knowable and knowable by human beings. God could no longer be the source of knowledge. That the universe is knowable presumes a materialist cosmology (a view of the cosmos): the visible is the real ('what you see is what you get'); there is no other universe worth knowing apart from the material world humans perceive with their senses.

The nineteenth-century mind was characterised by what Donald Lowe has called the bourgeois mode of perception.1 This meant a materialist cosmology and a realist view of the world. These corresponded to the qualities of mind of the individual entrepreneur on whom nineteenth-century capitalism was built. This cosmology broke with earlier cosmologies in which the world that mattered was the one behind or above the visible world and in which God, the Devil, and salvation were all more important than material reality. In that cosmology the representation of reality was judged in terms of its connection to the divine.

While the bases for the new bourgeois culture of realism were laid in the eighteenth century, only in the nineteenth century did it triumph. Philip Nord has shown that this culture was carried by new elites: Freemasons, Protestants, Jews, lawyers, university professors and students, all of whom were active in implementing republicanism.2 In a broad sense, the Republic was only possible in a realist culture. To be sure, there is no simple correspondence between this culture and republicanism, although there is a broad congruence, but republicanism flourished only in this culture. It had four key aspects. First, it was based on a secular and materialist cast of mind, assuming that human beings using Reason could know the world by analysing the material world rather than by searching the mind of God or the teachings of Jesus.

Second, it was masculine. Since the eighteenth century, Reason and the public sphere had been associated with men, while Nature and the private sphere were linked to women. That was the basis for their exclusion from citizenship in the Revolution. This ideology was most at home in freemasonry as opposed to the Church, in science and the law as opposed to theology and the army, in the professional bourgeoisie as opposed to the nobility.

Third, it perfected representation of the world in terms of realism. Realism in the broad, philosophical sense refers to the assumption that the visible is the real and thus the representation OI reality is best achieved by likeness. Realism presumes that the world has a real, objective existence, that it is knowable, that human beings can picture and describe it - represent it - accurately, 'as it really is'.

And, fourth, this culture analysed the world in terms of linear development over time. We can see this in the emergence of narrative over time as the dominant way of understanding the world, especially in the realist novel and history. We can understand it in the mode of operation of the individual capitalist, who had to take money and increase it over real time.

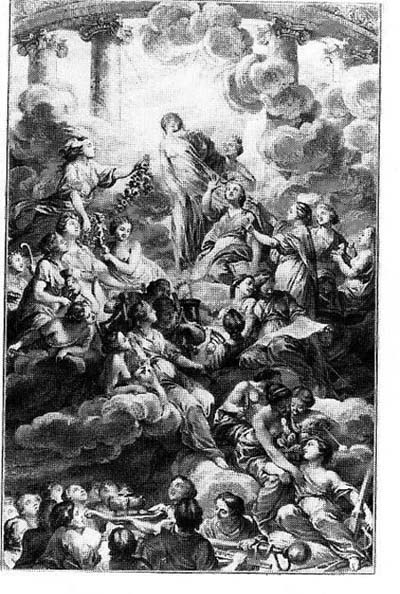

Frontispiece to Enclyopédie* (1751-65).

Truth attended by Reason and Philosophy surrounded by Geometry, Physics, Astronomy, Optics, and other mythologized Forms of Knowledge.

*The Enclyopédie was a multivolume work done by the philosophes of the eighteenth century Enlightenment to capture the highest level of contemporary knowledge in a broad range of fields.

Paul Broca (1824-1880)

. . . the two fundamental tenets of republican science were materialism and atheism. They are typified in the career of the eminent scientist doctor Paul Broca, who founded the Paris Anthropological Society in 1856. He is famous for the discovery of the part of the brain that governs speech, which is still called Broca's lesion. This discovery led to the expectation that the rest of the brain would soon be understood in the same way and that the human psyche -- what believers called the soul -- would ultimately be reduced to its material base. In that expectation, Broca left his brain to the Musée de Homme, a museum of anthropology.

Broca therefore believed that brain size and intelligence were related, that 'there is a remarkable relationship between the development of intelligence and the volume of the brain'. This paradigm was universally accepted throughout the European scientific community because it replicated the hegemonic assumptions of nineteenth-century European society. Broca and his disciples were neither racist nor misogynist by the standards of their time. They were committed republicans, whose materialist and positivist attitudes were linked to progressive social and political views. Despite their good intentions, however, their paradigm helped to justify the conquest of colonies and the exclusion of women from the public sphere. As Broca put it, 'in general, the brain is larger in mature adults than in the elderly, in men than in women, in eminent men than in men of mediocre talent, in superior races than in inferior races'. (In fact, brain size is irrelevant to intelligence. . . .