Charles Sowerwine, “The Social and Cultural Bases of Republicanism” in France since 1870: Culture, Politics, and Society

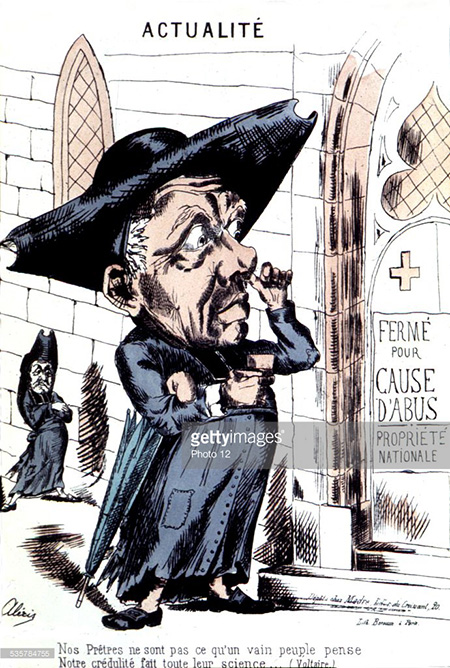

Anti-Clericalism

The word 'anticlericalism' appeared first in the Littre Dictionary in 1877. Its  appearance signifies the extent to which it had become a significant political movement. In Sanford Elwitt's words, 'The republican bourgeoisie found in the clerical issue the unifying factor essential to the solidarity of the republican coalition.'6

appearance signifies the extent to which it had become a significant political movement. In Sanford Elwitt's words, 'The republican bourgeoisie found in the clerical issue the unifying factor essential to the solidarity of the republican coalition.'6

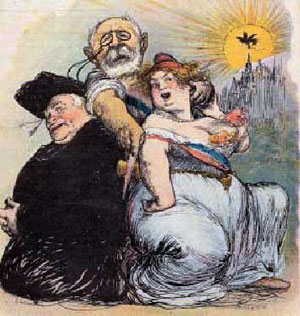

Bourgeois men feared the Church as a threat to male hegemony in the family. In his celebrated essay La Femme (Woman - 1859), Jules Michelet argued that bourgeois women were under the thrall of the priest, whom Michelet called 'the husband's rival and his secret enemy'. During confession women confided sexual secrets to the priest, who thus knew a man's 'secret weaknesses'. The Church's increasing struggle against contraception led priests to question sexual habits and this seemed to confirm men's fears. And bourgeois families often recognised the Church's sexual hold implicitly by giving religious education to women, for reasons of 'morality'. Michelet's essay was quickly retitled 'Priest, Woman, and Family' and remained popular throughout the Third Republic. Zola carried this conviction to the point of paranoia in his novel La Conquete de Plassans (A Priest in the House- 1874), in which a priest uses his charm with the bourgeois women of a provincial town to sap the republican convictions of the men. And in Roger Martin du Gard's Jean Barois (1913), the protagonist's marriage breaks down because his wife maintains her Catholicism against rationalist Dreyfusard convictions.

Many turned away from the Church, men more than women. Ralph Gibson has noted that while in religious areas like Nantes at the turn of the century 98 per cent of women attended mass against 91 per cent of men; in irreligious areas like Chartre in the same period, only 17 per cent of women attended against 2 per cent of men! More than half of France was considered 'tepid' in its religious duty. The Paris basin and other areas were 'missionary' territory. In such areas, as men enjoyed the social space of the cafe, the club, and the game of boule, the Church became a feminine space. Madeleine Pelletier recalled her mother's profound religious devotion as a chance to have her own space and perhaps to get back at her husband. 'Back at the house, [my mother] repeated the sermon for my father; she had a great natural eloquence and was merciless in her sermons: the damned one, despite his supplications, rolled from abyss to abyss in a vast cave "filled with fire-damp".... The cafe owner across the street was said to be a Freemason and my mother loathed this association. She asserted that before dying her greatest joy would be to strangle a Freemason.'

Many turned away from the Church, men more than women. Ralph Gibson has noted that while in religious areas like Nantes at the turn of the century 98 per cent of women attended mass against 91 per cent of men; in irreligious areas like Chartre in the same period, only 17 per cent of women attended against 2 per cent of men! More than half of France was considered 'tepid' in its religious duty. The Paris basin and other areas were 'missionary' territory. In such areas, as men enjoyed the social space of the cafe, the club, and the game of boule, the Church became a feminine space. Madeleine Pelletier recalled her mother's profound religious devotion as a chance to have her own space and perhaps to get back at her husband. 'Back at the house, [my mother] repeated the sermon for my father; she had a great natural eloquence and was merciless in her sermons: the damned one, despite his supplications, rolled from abyss to abyss in a vast cave "filled with fire-damp".... The cafe owner across the street was said to be a Freemason and my mother loathed this association. She asserted that before dying her greatest joy would be to strangle a Freemason.'