Miriam R. Levin, “Bringing the Future to Earth in Paris, 1851 – 1914

The Ideal of Progress in the Second Empire

During the 1850s and 1860s, Emperor Napoleon III’ s goal was to turn Paris into a hub of industrial capitalism, where investments in urban development would stimulate

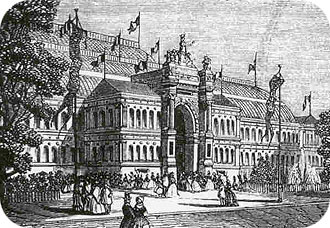

Palace of Industry, 1867 Paris Exhibition |

economic growth and general prosperity. Ceding control of the university and schools to the Catholic Church in exchange for its political backing of his regime, the emperor still had a wide set of possibilities open to him as he centered power around himself. To assist him, he appointed a cadre of like-minded administrators, engineers, and bankers to various commissions and government posts. Prominent among them were his extremely able prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, and a number of graduates of the École Polytechnique (EPT), some of whom were strongly influenced by Saint-Simon’s social philosophy. [Saint-Simon was an early socialist who argued in the late 18th and early 19th century that scientifically trained elites should oversee the development of modern economies. His ideas had a great influence on many of the leaders of the Second Empire.]

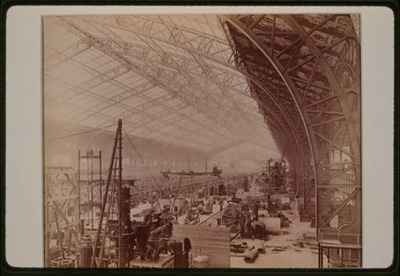

Installation of the Hall of Industry, 1889 Paris Exposition |

After assuming his position in 1853, Haussmann marshaled the talent and resources to realize this vast, coordinated project. He looked to a state employed engineering and architectural elite to design and administer this transformation through private contractors and free labor. . . . They also used universal expositions in the capital to advance the emperor ’s building projects, as well as to celebrate industry and material progress itself….

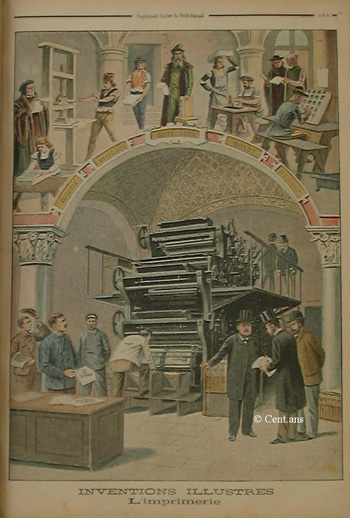

Napoleon III and his équipe [team]were men of what I call “salutary urban communications ” intent on putting human beings and a modern built environment into a smoothly functional, healthful, and aesthetically attractive interactive network. “Communications ” refers not simply to the material networks of telegraph, boulevards, transport, and gas and electric illumination that improved the circulation of people, goods, and capital but to a means of institutionally creating and rationally managing dynamiceconomic and social relationships within the city, connected nationally and internationally through an urban environment built out of the most advanced technologies available. They legislated a rational basis for aesthetics linked to functionality and the integration of new materials and methods of construction.

Through their centrally directed projects, they coordinated government, private banks, construction firms, realtors, and the vast working populations of Paris in a set of interdependent relationships, while rationally reconfiguring the social spaces within which residents and visitors consumed the fruits of this construction. In turn, building and living within these environments engendered dynamic changes in physical, material, and psychical existence. International expositions and museums arose from the commitment to rebuilding Paris and served as stimuli for further improving and extending this way of life into new spaces and to more people.

the vast working populations of Paris in a set of interdependent relationships, while rationally reconfiguring the social spaces within which residents and visitors consumed the fruits of this construction. In turn, building and living within these environments engendered dynamic changes in physical, material, and psychical existence. International expositions and museums arose from the commitment to rebuilding Paris and served as stimuli for further improving and extending this way of life into new spaces and to more people.

The impact of the emperor ’ s efforts was profound; his vision, however, could not be fully realized. The economics didn’t work, and so construction slowed, stopped, or occurred erratically. The growing and increasingly segregated working classes did not share in the benefits of the transformed city. The hold of the church and of loyal Catholics over instruction blocked the formation of a new generation of scientists, engineers, and technical personnel trained in research and modern applications to replace the old cadre. And finally, the static nature of the goals to which the emperor directed change, combined with the failure of his efforts to liberalize the political system, left the future of the culture of change at an impasse by 1870. The war with Germany, the siege of Paris, and then the formation of the Commune necessitated a recasting of this past effort, though not a complete break.