Frederick Brown, The Battle for the Soul of France; Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus

Warring Memories of the War and the Commune

Had France's defeat been a fortunate fall? Men prominent in the ranks of Napoleon III's left-wing opposition felt

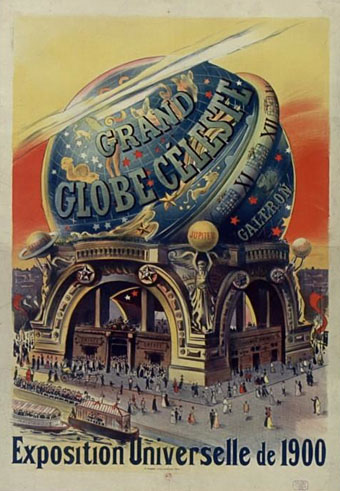

Celestial Globe at the 1900 Paris Exposition |

that the country had indeed been brought to its senses when brought to its knees. They beheld the future as an opportunity for France, freed from the shackles of Bonapartism, to leap forward, secularize civic institutions, and confer upon science the prestige it enjoyed across the Rhine. Germany's military success, according to Ernest Renan, an eminence at the College de France, was the product of "Germanic science, Germanic virtue, protestantism, philosophy, Luther, Kant." Higher educational institutions in France, he wrote, "have been too influenced by the Jesuits, their latin verse, and stale orations ... France's malady is its need to speechify." Renan's Moral and Intellectual Reform validated the agenda of politicians who went on to found the Third Republic and, at eleven-year intervals - in 1878, 1889, 1900 - organize universal expositions that presented France as the champion of liberty, the impresario of science and technology, the genial host clasping nations in a spirit of exuberant cosmopolitanism. Those republicans known as "opportunists" who made policy in the late nineteenth century set their sights beyond Alsace-Lorraine. Their aim was to regain French stature on a world stage.

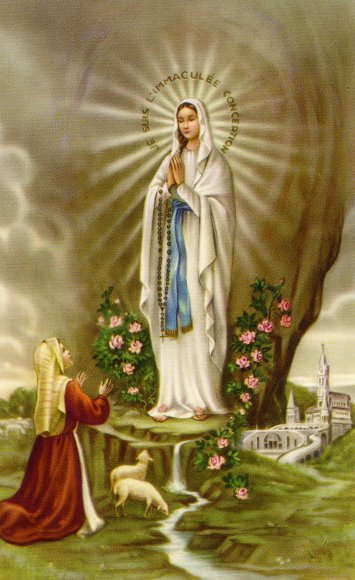

In other quarters, cosmopolitanism, far from reflecting well upon the State, was seen as tantamount to profanity or treason. The many for whom military defeat followed by civil war had opened an abyss found safe purchase in ideas of transcendence or innateness: in fervent celebration of Christ's bleeding heart, miracles, and saints' relics (which multiplied), or in race. Pilgrims who assembled at sites sanctified by visitations from Mary heard bishop after bishop insist that France wanted salvation, not enlightenment. She had lost the war for having strayed from godliness and would find her way home again only as a penitent determined to right wrongs that descended from the original sin of eighteenth-century regicides [i.e. those who brought about the execution of King Louis XVI during the French Revolution]. Salvation was also the cry and the promise of nationalists, whose most eloquent voices argued the sacredness of soil, the virtue of roots, the infallibility of instinct, and subversiveness of intellect To them "fin de siècle" [end of century] in most of its manifestations signified decadence.

Painting of Bernadette's 1858 Vision of the Virgin at Lourdes |

Although nativist gospe an a religion proclaiming 1ts unversality [i.e. French nationalists and Catholicism] did not always occupy common ground, both the politics of bereavement embraced by the Church and the reverence for ancestral Frenchness exemplified by the writers Maurice Barres and Charles Maurras oriented believers of one kind and the other toward the past. The past was, above all, a refuge from the dangerous mobility of people and things. It was stillness, order, containment. "The qualities I love in the past are its sadness, its silence, and most especially its fixity. Everything that moves disconcerts me," wrote Barres (who must have reconciled his aversion to movement with his cult of "national energy").

The ideal of a guarded, self-referential nation schooled in the imperative of war flourished outside the pale of universal expositions. Among subscribers to that ideal, revanchism was synonymous with patriotism and Germany was an indispensable threat. But no less indispensable than the ogre next door was the alien within. Like Catholicism, nationalism had its ritual Judas. And these two forces converged as never before during the tumultuous nineties, in the Dreyfus Affair.11