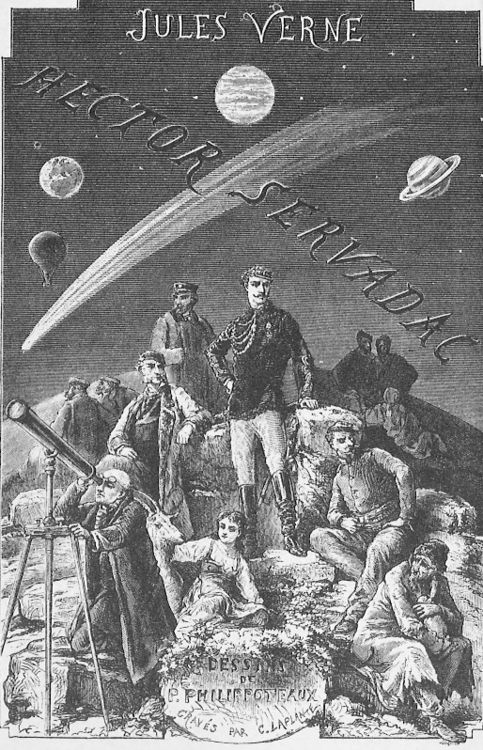

Jules Verne, Off on a Comet (Hector Servadac), 1877

|

Anti-Semitism was a common element in late nineteenth-century

French culture to an extent that is shocking today.

Below are several passages from the original English

translation of Hector Servadac a novel by Jules Verne, one of

the chief founders of modern science fiction.

In the original 1877 version of the novel, which was

serialized in a magazine for young people, the description of a

Jewish character contained all of the negative stereotypes that

were repeated endlessly in French culture at the time.

This figure is named Isaac Hakkabut, but that name is

rarely used in the novel, and, instead, he is almost always

called “the Jew,” thereby implying that his personal qualities

are universal characteristics of all members of his ethnic

group. He is

described as ugly and anti-social, and his function in the story

is chiefly as the subject of jokes about how greedy he is. The chief rabbi of Paris complained that the anti-Semitic imagery was very inappropriate, particularly in a publication aimed at young people, and Verne’s publisher made minor changes for the later editions, primarily substituting the character’s name for “the Jew.” The English translation, however, was based on the serialized version.

Here are a few of the more

objectionable passages. |

He took the cue, and promptly ordered the Jew to

hold his tongue at once. The man bowed his head in servile submission, and folded his hands upon his breast.

submission, and folded his hands upon his breast.

Servadac surveyed him leisurely. He was a man of

about fifty, but from his appearance might well have been taken for at

least ten years older. Small and skinny, with eyes bright and cunning, a

hooked nose, a short yellow beard, unkempt hair, huge feet, and long

bony hands, he presented all the typical characteristics of the German

Jew, the heartless, wily usurer, the hardened miser and skinflint. As

iron is attracted by the magnet, so was this Shylock attracted by the

sight of gold, nor would he have hesitated to draw the life-blood of his

creditors, if by such means he could secure his claims.

His name was Isaac Hakkabut, and he was a

native of Cologne. Nearly the whole of his time, however, he informed

Captain Servadac, had been spent upon the sea, his real business being

that of a merchant trading at all the ports of the Mediterranean. A

tartan, a small vessel of two hundred tons burden, conveyed his entire

stock of merchandise, and, to say the truth, was a sort of floating

emporium, conveying nearly every possible article of commerce, from a

lucifer match to the radiant fabrics of Frankfort and Epinal. Without

wife or children, and having no settled home, Isaac Hakkabut lived

almost entirely on board the Hansa,

as he had named his tartan; and engaging a mate, with a crew of three

men, as being adequate to work so light a craft, he cruised along the

coasts of Algeria, Tunis, Egypt, Turkey, and Greece, visiting, moreover,

most of the harbors of the Levant. Careful to be always well supplied

with the products in most general demand—coffee, sugar, rice, tobacco,

cotton stuffs, and gunpowder—and being at all times ready to barter, and

prepared to deal in secondhand wares, he had contrived to amass

considerable wealth. . . .

----

The count turned his back in disgust, while the

Jew sidled up to little Nina and muttered in Italian. “A lot of lies,

pretty one; a lot of lies!”

“Confound the knave!” exclaimed Ben Zoof; “he

gabbles every tongue under the sun!”

“Yes,” said Servadac; “but whether he speaks

French, Russian, Spanish, German, or Italian, he is neither more nor

less than a Jew.” . . .

----

A month passed away. Gallia continued its course, bearing its little

population onwards, so far removed from the ordinary influence of human

passions that it might almost be said that its sole ostensible vice was

represented by the greed and avarice of the miserable Jew.