The Dreyfus Affair as a Religious War

Robert Gildea, Children of the Revolution: The French, 1799-1914 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2008), pp.273-279.

The clamour from the end of 1897 that Captain Dreyfus had been the victim of a miscarriage of justice and that his case should be reopened was a direct challenge to those

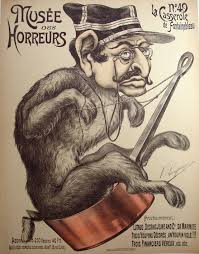

Anti-Semitic Cartoon of Captain Dreyfus |

Catholics who believed that France could be saved only by eliminating the influence of Jews, Protestants andfreemasons. At the head of those fighting for a judicial review were Dreyfus' brother Mathieu and Joseph Reinach, former associate of Gambetta and deputy of Digne, Bernard-Lazare and Leon Blum, which gave some substance to the Catholic accusation that the campaign was led by a 'Jewish syndicate'. Zola, if not a Jew, was denounced by Barres as a 'deracinated Venetian.' [Zola;s family had originated in Italy.] The involvement of leading Protestants such as the Alsatian Auguste Scheurer-Kestner provoked parallel attacks on Protestants who were considered half-Jews by Drumont -- rich, clever, cosmopolitan and therefore traitors to the national interest. Polemics such as Pierre Froment's Protestant Betrayal and Ernest Renauld's Protestant Peril in 1899 argued that Protestantism had stood for 'continuous revolution' in France since 1789, that Protestants had conquered all the top posts in state and society, that the godless school was an instrument of 'Protestant dechristianization' and that Protestants supported Germany and Great Britain as Protestant powers against Catholic France.53 Charles Maurras launched an attack against the Monad family of formerly Swiss Protestant pastors and professors, a 'state within a state' who were corrupting French universities with their Germanic science and had thrown themselves into 'the hysteroepilepsy of dreyfusism'.54 Freemasons too were subjected to attacks, since the whole masonic enterprise was thought to be a Jewish invention, notably by Jules Lemaitre of the Ligue de la Patrie Française'

in his 1899 Franc-marçonnerie.

To begin with, the big blows were struck by the antidreyfusard camp. Emile Zola was put on trial for libel and found guilty. Outside the courtroom Jules Guerin's Anti-Semitic League fomented trouble and beat up Joseph Reinach. In the elections of 1898 Reinach failed to get re-elected at Digne whereas Drumont was returned at Algiers and twenty-two anti-Semitic deputies took their place in the Chamber. At a prize-giving at the Dominican college of Arcueil Pere Didon defended the army as 'the guardian of law, the spotless knight of justice' ,55 Six weeks later, when Colonel Henry slit his throat in Mont-Valerien prison and Joseph Reinach suggested that he had framed Dreyfus, Drumont's La Libre Parole opened a subscription 'For the widow and orphan of Colonel Henry against the Jew Reinach', to pay for her widowhood and for libel proceedings against ReinachY The Dreyfus case was finally reopened in 899, sitting out o f the way in Rennes. Attending it, Maurice Barres visited the nearby chateau of Combourg, where Chateaubriand had been raised, and observed, 'that Dreyfus is capable of treachery, I know from his race.' Dreyfus was again found guilty, albeit with 'extenuating circumstances'.

f the way in Rennes. Attending it, Maurice Barres visited the nearby chateau of Combourg, where Chateaubriand had been raised, and observed, 'that Dreyfus is capable of treachery, I know from his race.' Dreyfus was again found guilty, albeit with 'extenuating circumstances'.

'Writers, scholars, artists, professors! ... this penetration of "intelligence" filled us with joy,' Leon Blum later wrote of the Affair, which for many historians saw the birth of the French intellectual, committed to a public cause.58 More powerful at the time, however, was the dreyfusards' sense of being a small group of apostles, persecuted for their commitment to truth and justice, ready if necessary to sacrifice themselves as martyrs to the cause. 'I hope that from my first article', wrote Zola, 'I became one of the band.' 'Whoever suffers for truth and justice', he told the jury at his trial, 'becomes august and sacred.'59 They saw themselves fighting against both prejudice and lies, called by Anatole Leroy-Beaulieu 'the doctrines of hatred', and against the arbitrary power of the army and for many months the state.60 They were refighting the battles of the French Revolution, setting up the Ligue des Droits de l'Homme at the time of the Zola trial, but they also identified with Voltaire's battles against the intolerant Catholic Church, the single religion of the absolutist state before 1789. . . . Other dreyfusards went back to medieval times to find paral lels of religious persecution. Camille Pelletan denounced the Dominican Pere Didon as 'truly the heir of those ferocious devots whose order was founded to massacre heretics and in the Middle Ages put the south of France to fire and sword', adding that he had forged 'a holy alliance between habit and plume, between sabre and holy-water sprinkler'.63 Going back to Biblical times the Protestant Ferdinand Buisson, one of the founders of the Ligue des Droits de l'Homme, condemned 'Phariseeism, which is worse than antiSemitism ... the clerical, military, judicial or political Phariseeism that says: there is no Dreyfus Affair'. 6

Eventually the republican state stepped in to deal with the Catholic and anti-Semitic assault that was deemed to threaten not only Jews, Protestants and freemasons but the Republic itself. The Waldeck-Rousseau ministry was formed under the banner of 'republican defence' and Waldeck had recourse to law to impose restrictions on the Catholic Church.