The Dreyfus Affair: Embattlement and Republican Defence

Robert Gildea, Children of the Revolution: The French, 1799-1914 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2008), pp.273-279.

Here is a detailed description of the manner in which the Dreyfus Affair tore apart the French political system and helped created the kind of violent right-wing groups that presaged the fascist movements that would plague European politics in the first half of the 19th century. Gildea supplies more detail than you need for our purposes and refers to many political and intellectual figures that are not particularly relevant to our explorations. You will need to carefully pull out the main threads of the affair and ignore some of the details that are not useful for our purposes. Nonetheless this account can provide a sense of how divisive the Dreyfus Affair was and how it sat the stage for a new era in French politics.

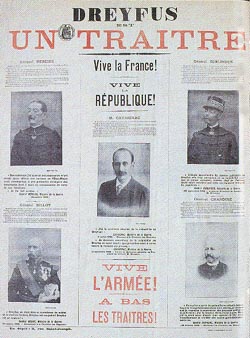

In December I894 a General Staff officer of Alsatian-Jewish origin, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, was court-martialled for passing French military secrets to the German army. After a ceremonial degradation in the courtyard of the Ecole Militaire on 5 January 1895, when his emblems of rank were torn from his tunic and his sword broken, he was sent as a

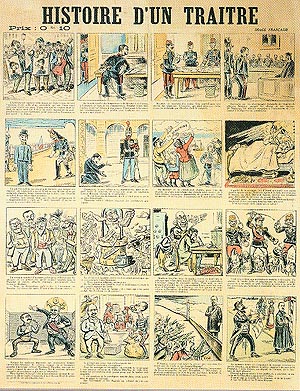

"The Story of a Traitor" |

traitor to Devil's Island off French Guiana. Little sympathy surrounded him: writing in La Justice on Christmas Day

1894 Clemenceau criticized the lightness of the punishment which would have been much harsher for an ordinary soldier, and demanded the death penalty.58

Almost two years later a small group of individuals began to

suspect that Dreyfus had been framed by his superior officers in order to cover the guilt of a Gentile officer who was much more closely integrated into the patronage system of the army. This group was partly Jewish- Alfred's brother Mathieu, the former Gambettist and editor of La Republique Françaises, Joseph Reinach, the anarchist Bernard Lazare and the lawyer and intellectual Leon Blum. It was also partly Alsatian, and thus marginal but keen to demonstrate its patriotism. [Alsace was the formerFrench province that had become a part of the new German Empire as a result of the Franco-Prussian War] Colonel Picquart, head of the army's Intelligence Service, who had taught Dreyfus at military school, began to suspect Major Ferdinand Esterhazy, a flamboyant nationalist, and reported his concerns to his superiors and Meline's war minister, General Billot. Rather than explore that line they posted Picquart to Tunisia in January 1897· Granted a short leave in June

1897 Picquart  returned and made contact with a lawyer who had

been his contemporary at the Lycee of Strasbourg, Louis Leblois. On 13 July 1897 Leblois met the patron of all Alsatian republicans and Protestants, Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, who was immediately converted to the possibility of a miscarriage of justice. ScheurerKestner went straight to the top, calling on President Faure, General Billot and premier Meline. None of them wanted to have anything to do with his concerns and claimed that he had no evidence warranting a fresh look at the case. Meline announced to the Chamber on 4 December I897, 'There is no Dreyfus Affair.'59

returned and made contact with a lawyer who had

been his contemporary at the Lycee of Strasbourg, Louis Leblois. On 13 July 1897 Leblois met the patron of all Alsatian republicans and Protestants, Auguste Scheurer-Kestner, who was immediately converted to the possibility of a miscarriage of justice. ScheurerKestner went straight to the top, calling on President Faure, General Billot and premier Meline. None of them wanted to have anything to do with his concerns and claimed that he had no evidence warranting a fresh look at the case. Meline announced to the Chamber on 4 December I897, 'There is no Dreyfus Affair.'59

More than that, the rumour began to spread in the autumn of 1897 that this troublemaking, designed only to bring the army into disrepute and weaken the nation, was the conspiracy of a 'Jewish syndicate'. This story was spread not only by hardline anti-Semites such as Drumont but by Catholic leaders such as Albert de Mun who denounced the 'occult power' behind the campaign and by left wing nationalists like Henri Rochefort . . . The weight of opinion against the 'syndicate' pulled socialists along in its wake. . . .

In fact Esterhazy was brought to court martial on 10-11 January 1898, a ploy by the military to clear the air, for he was promptly acquitted. This triggered a second phase of the Affair: an open letter to the president of the Republic, entitled J'accuse, penned by the novelist Emile Zola, and published on 13 January I898 in L'Aurore by Clemenceau who had changed his mind in mid-course. Zola denounced the cover-up by the military, naming war minister General Mercier,

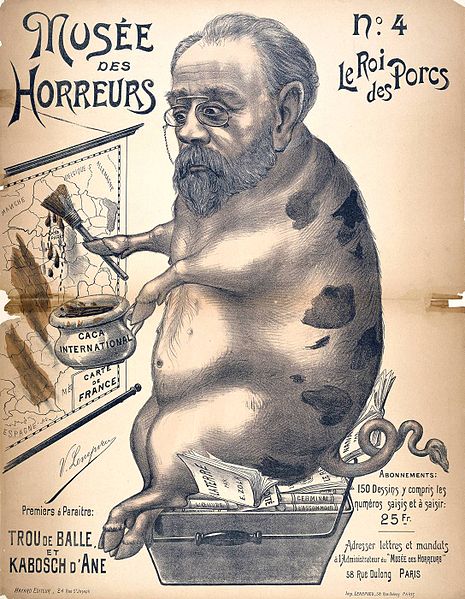

Caricature of Zola, Victor Lenepveu, "The King of the Pigs" (1899-1900) from the Museum of Horrors series |

chief of General Staff General de Boisdeffre and Commandant du Paty de Clam as the officers concerned, issued warnings about military despotism, and perorated on the inevitable triumph of truth and justice.6' He was supported by a manifesto of intellectuals, among whom were Anatole France and Marcel Proust, published on 14 January, by Charles Peguy, a graduate of the Ecole Normale Superieure, who spread the word from his Bellais bookshop in the rue Cujas, and by avant-garde journals such as La Revue Blanche, run by the art-critic Natanson brothers.62 These intellectuals, however, remained a small minority. Of the fifty-five daily newspapers in January and February r898, forty-eight were anti-dreyfusard.63 Zola as sent to trial on 7 February 1898 for defamation and sentenced to a year in prison,

although he managed to escape to England. Outside the courtyard hostile crowds were orchestrated by Jules Guerin and his newly formed Ligue Anti-Semitique, composed mostly of butchers' boys from the abattoirs [slaughter houses]of La Villette.64 . . . AntiSemitic riots broke out in the main cities of France, degenerating in Algiers into a veritable pogrom.66 The only response of note on the dreyfusard side was the foundation of the Ligue des Droits de

l'Homme, primarily by freemasons, Jews and Protestants, who had

themselves been persecuted before the Revolution, in order to fight for human rights and tolerance.67

Intellectuals without electoral concerns might join the highly exposed Dreyfusard camp. Politicians with elections to fight in May 1898 did not. In those elections the Dreyfus Affair was not an issue: to mention it was electoral suicide. Any politician suspected of favouring Dreyfus was unceremoniously abandoned: thus not only Joseph Reinach but also Jean Jaures and Jules Guesde lost their seats . . . The election saw the return of twenty-two self-confessed anti-Semites, notably Edouard Drumont in Algiers, where the Ligue Anti-Semitique had been his electoral agents. The main result of the elections was defeat for Jules Meline as opinion shifted to the left, and a radical [i.e. a member of the Radical Party, which was in fact, not that radical], Henri Brisson, was appointed premier. The move to the left however, did nothing for the case of Dreyfus. Brisson's war minister, Godefroy Cavaignac, told the Chamber on 9 July 1898 that he had irrefutable proof of Dreyfus' guilt. The son of the republican dictator of 1848, he saw himself as a soldier in all but name, while Reinach described him as

'the Robespierre of patriotism', determined to put the national interest

above individual rights.68 His certainty about Dreyfus' guilt was punctured by the Preuves published by Jean Jaures, and suspicion for framing Dreyfus now fell on Colonel Henry of the Intelligence Section. Arrested and confined in the fortress of Mont-Valerien, Henry slit his throat on 31 August 1898, evidence of his guilt for dreyfusards and of his martyrdom for antidreyfusards.

Antidreyfusards now had the wind behind them. The defeat of

the moderates around Meline removed the plank along which the

'rallied' royalists and Bonapartists sought to return to power. There had always been royalists and Bonapartists [i.e. supporters of a return to power of Napoleon's family] critical of the Ralliement [Catholic supporters of the Republic]; now the initiative shifted to them as it seemed that they would never gain control of the parliamentary Republic, so it must be destroyed. In the autumn of 1898 anti-parliamentary leagues gathered shape and momentum, putting the parliamentary Republic in danger. The royalist pretender [i.e. the next in line to be king if the monarchy was restored], now the Due d'Orleans, saw the possibility of using the popular fighting-force provided by the Ligue Anti-Semitique as a route back to power. Jules Guerin and a selection of his butchers' boys were introduced to the duke in his Brussels exile on 24 January 1899, and royalist money for the Ligue was channelled by Boni de Castellane, who had married the American heiress Anna Gould, and by Andre Buffet, son of the Orleanist Louis Buffet, who had been a Moral Order premier in I875.69 The Ligue des Patriotes, dissolved after the Boulanger Affair, was reconstituted in September 1898 by Paul Deroulede, who was elected deputy for Angouleme in 1898. Resistant to pressure from his militants to embrace anti-Semitism, he was if anything Bonapartist, and was looked to by Bonapartist leaders . . .

Antidreyfusards now had the wind behind them. The defeat of

the moderates around Meline removed the plank along which the

'rallied' royalists and Bonapartists sought to return to power. There had always been royalists and Bonapartists [i.e. supporters of a return to power of Napoleon's family] critical of the Ralliement [Catholic supporters of the Republic]; now the initiative shifted to them as it seemed that they would never gain control of the parliamentary Republic, so it must be destroyed. In the autumn of 1898 anti-parliamentary leagues gathered shape and momentum, putting the parliamentary Republic in danger. The royalist pretender [i.e. the next in line to be king if the monarchy was restored], now the Due d'Orleans, saw the possibility of using the popular fighting-force provided by the Ligue Anti-Semitique as a route back to power. Jules Guerin and a selection of his butchers' boys were introduced to the duke in his Brussels exile on 24 January 1899, and royalist money for the Ligue was channelled by Boni de Castellane, who had married the American heiress Anna Gould, and by Andre Buffet, son of the Orleanist Louis Buffet, who had been a Moral Order premier in I875.69 The Ligue des Patriotes, dissolved after the Boulanger Affair, was reconstituted in September 1898 by Paul Deroulede, who was elected deputy for Angouleme in 1898. Resistant to pressure from his militants to embrace anti-Semitism, he was if anything Bonapartist, and was looked to by Bonapartist leaders . . .

More bourgeois and respectable, less plebeian and streetwise, was the Ligue de la Patrie Française founded in January 1899 by two secondary school teachers, Henri Vaugeois and Gabriel Syveton. Their ambition was to bring over a majority of the Academie Française in order to demonstrate that not all intellectuals were dreyfusards, and they began with the poet François Coppee and the playwright and critic Jules Lemaitre. Maurice Barres delivered a keynote lecture to them, arguing that France had been desiccated and divided by a cerebral, Jacobin [the Jacobans were a radical faction in the original French Revolution] notion of the patrie [nation]peddled by philosophy teachers and that a deep and unifying nationalism had to be generated by a cult of the soldiers of 1870 who lay in graves in Alsace, now art of Germany, the cult of la terre et les morts [the land and the dead]. The high point of the Ligue came with the municipal elections of

1900, when several of them were voted on to the Paris municipal council, which was now captured by conservatives. Even before then Henri Vaugeois had branched off to join the left-bank journalist Maurice Pujo and Provençal regionalist Charles Maurras to found an Action Française Committee (April 1898), then an Action Française Bulletin (July I 899 ). Maurras had converted to monarchism during a visit to the eastern Mediterranean in 1896 when he realized how little influence republican France had in comparison to the monarchical empires of Great Britain, Germany and Russia. The Dreyfus Affair convinced him that the Republic had fallen into the hands of the 'four confederate states' of Jews, Protestants, freemasons and foreigners, and that only a restored monarchy could bring back a strong state, a united nation and national greatness. His approach to monarchism was theoretical rather than sentimental and his relationship with the Due d'Orleans and his staff was decidedly ambivalent. Unlike the Ligue de la Patrie Française, Action Française had no truck with elections but communicated its ideas through its publications and street demonstrations and put its faith in a coup de force.

Jules Dalou's Triumph of the Republic (1889) |

The turning point of the Dreyfus Affair came in the summer of

1899. On 31 May Deroulede, charged with attacking state security on 23 February, was acquitted by the Assize Court of the Seine. On 11 June Colonel Marchand, who had confronted British forces at

Fashoda on the Upper Nile but been recalled by the government,

made a triumphant procession through Paris.7 3 On 3 June the Cour de Cassation decided that the case for revising the Dreyfus conviction had to be answered, and referred the matter back to the court martial. The next day right-wing demonstrators assaulted the new president Loubet, who was thought to favour reopening the case, at the Auteuil races, and knocked his top hat off. Loubet now summoned Waldeck Rousseau to form a government of so-called 'republican defence' that would bring together broad support for the regime and defuse the Dreyfus Affair. His ministry of 22 June 1899 was composed of former supporters of Meline who now broke with him over his refusal to deal with the Dreyfus Affair. . . . Most significantly, to draw in the left wing he appointed Alexandre Millerand as trade minister, the first time a socialist had held government office. Waldeck pushed through a raft of reforms including an Associations Law of 1901 which permitted trade unions to own property collectively, a factory act which limited the working day first to eleven hours and later to ten, and a pensions bill that did not become law till 1910.

Waldeck's government acted fast to secure the regime. The arrest of Jules Guerin and his royalist backer ndre Buffet was ordered for threatening state security. Guerin holed up with his Ligue in their offices in the rue Chabrol, near the Gare du Nord, and police were sent in for what became known as 'the siege of Fort Chabrol'. The retrial of Dreyfus by court martial was conducted for security reasons outside Paris, in Rennes. Had he been acquitted General Mercier and the military top brass would have been liable to prosecution for obstructing the course of justice, and might have resorted to a coup d'etat, but on 9 September the court again found Dreyfus guilty, by a majority vote, 'with extenuating circumstances', whatever they might be. This opened the way to a pardon being granted by President Loubet on 19 September, which did nothing to satisfy the dreyfusards, who dreamed of a formal acquittal and punishment of the guilty generals. 'Once again it is up to us poets', Zola wrote to Madame Dreyfus, 'to nail the guilty to the eternal pillory.' Only the right-wing civilian conspirators were charged with conspiracy and effectively dealt with. The Senate sat as a high court from November 1899 till January 19oo, condemning Guerin to ten years in prison and Deroulede and Buffet to five years' exile.76 As if to mark this success the final, bronze-cast version of Dalou's Triumph of the Republic was unveiled on 19 November 1899 on the place de la Nation in the presence of President Loubet and premier WaldeckRousseau.77 Finally, in June 19oo Waldeck secured the Chamber's approval of a bill to amnesty all those implicated in the Affair, cunningly quoting what his first political master Gambetta had said about amnestying the Communards. "'When disagreements have divided and torn apart a country,' he repeated, "all men of political wisdom understand that the time comes when these need to be forgotten." Messieurs, I think that the hour of which Gambetta spoke has arrived.'78

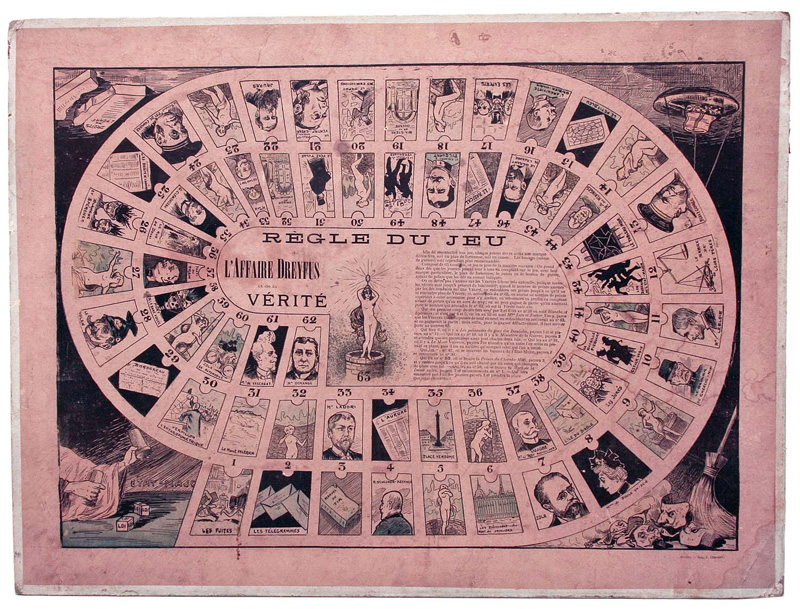

A Dreyfus Affair Board Game |