French Anti-Semitism

Robert Gildea, Children of the Revolution: The French, 1799-1914 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2008), pp.353-354.

In the passage below Robert Gildea describes the beginning of modern anti-Semitism in France. This is a case in which it is particular important to realize that, as a historian, he is paraphrasing the ideas of individuals at the time, not presenting his own interpretation of conditions in late 19th century France

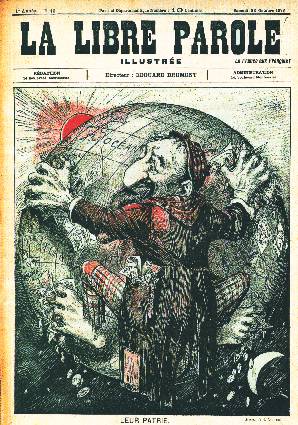

The cover of an issue of Drumont's newspaper, La Libre Parole, with a racist depiction of a Jew grasping the entire world with the caption "Their Country" -- implying that Jews thought that they owned the world |

Much more powerful than social reform as a way to building a bridge between Catholic conservatism and a popular base was antiSemitism. Edouard Drumont, whose father had been an official at the Hotel de Ville and early in the Second Empire the boss of Henri Rochefort, was a journalist who was increasingly unhappy with the opportunist Republic and with the influence over it of the Rothschilds and Reinachs. In 1886 he published La France juive, which sold over 1oo,ooo copies in its first year alone and made his fortune. Singlehandedly, he transformed anti-Semitism from a socialist ideology that had been peddled by Proudhon and certain Blanquists, which attacked the Jews as usurers and capitalists, into an allembracing condemnation of Jews for the evils of the modern world. They were said to embody parasitic finance capital, promoting large department stores at the expense of small shopkeepers and lending to peasants at extortionate rates. They were exposed as the power behind the republican political class, as bankers, newspaper magnates, publishers, members of the Academie Française, the theatre, schools and universities, who were increasingly divorced from and shamelessly exploited and deceived real, popular, eternal France. Ever since they crucified Christ they had ceaselessly attacked the Catholic Church, hatching freemasonry to launch the French Revolution. The divorce law of 1884 was the work of one Jew, Naquet, the law of 188o introducing lay education for young women that of another, Camille See. Most of Drumont's ideas were entirely ridiculous - the defeat of 187o was said to be a conspiracy of German Jews to take over France, Gambetta was a Jew from Genoa, Protestants were half Jewish - but the idea of a Jewish plot behind all contemporary misfortunes was highly seductive. Reviewing La France juive the socialist Benoit Malon pointed out that 'the proletariat and petite bourgeoisie suffer from capitalism as a whole, whether it is Jewish or non-Jewish.'45 And yet La Croix argued in 1894 that 'the social question is, fundamentally, the Jewish question.'46

Drumont gave focus to anti-Semitism in his slogan 'La France aux

Française' [France to the French] and in the arguments which were broadcast even more widely by the paper he founded in 1892, La Libre Parole. His ideas were taken up by other movements, not least by Catholics seeking to broaden their appeal and to find new weapons against the Republic. La Croix, founded by the Assumptionists in r88o and edited by Vincent de Paul Bailly, became a daily in 1883 and by 1895 had eighty-six departmental editions, most of them weeklies. It was aimed not at the bourgeoisie but at the lower clergy and a popular clientele; La Croix du Nord had a circulation of 23,ooo in 1899 and was read among others by textile workers, miners, small tradesmen and peasants. It embraced anti-Semitism in 1889 and the following year proclaimed itself 'the most anti-Jewish paper in France, because it is emblazoned by Christ, mark of horror for the Jew'. Sales rose from 6o,ooo in 1888 to 16o,ooo in 1892 and 2oo,ooo in 1899. Echoing La France juive, it blamed Jews for the capitalism that was destroying hard-working, traditional France, the liberalism that eased them into positions of power, and the Jewish press and education system that was undermining religion. In order to structure their support in the regions the Assumptionists set up Comites JusticeEgalite after 1896. When Dreyfus was arrested in 1894 it came as no surprise to the Assumptionists: Vincent de Paul Bailly described him as 'the Jewish enemy betraying France'