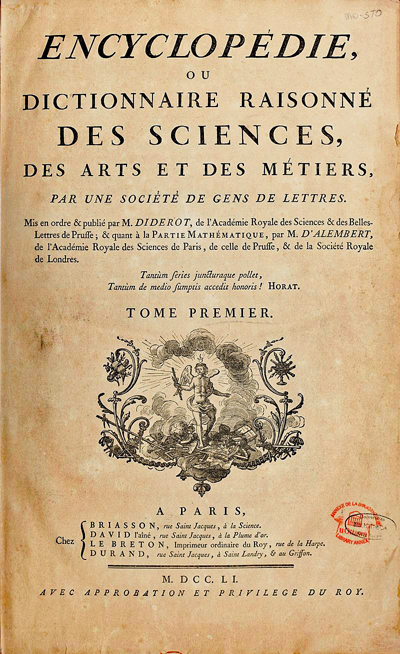

Day 14 -- Condorcet, Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Human Mind (1793)

|

The MARQUIS de CONDORCET, (1743-1794), was a French mathematician,

[NB – As a practitioner of 18th century rhetoric,

Condorcet liked long sentences and rhetorical questions.

But there is no question that he thought that the

Enlightenment would lead to a new era of peace, prosperity, and

progress for all humanity.] |

How

consoling for the philosopher who laments the errors, the crimes, the

injustices which still pollute the earth and of which he is often the victim

is this view of the human race, emancipated from its shackles, released from

the empire of fate and from that of the enemies of its progress, advancing

with a firm and sure step along the path of truth, virtue and happiness!

It is the contemplation of this prospect that rewards him for all his

efforts to assist the progress of reason and the defense of liberty. . . .

Such contemplation is for him an asylum, in which the memory of his

persecutors cannot pursue him; there he lives in thought with man restored

to his natural rights and dignity . . . .

How

consoling for the philosopher who laments the errors, the crimes, the

injustices which still pollute the earth and of which he is often the victim

is this view of the human race, emancipated from its shackles, released from

the empire of fate and from that of the enemies of its progress, advancing

with a firm and sure step along the path of truth, virtue and happiness!

It is the contemplation of this prospect that rewards him for all his

efforts to assist the progress of reason and the defense of liberty. . . .

Such contemplation is for him an asylum, in which the memory of his

persecutors cannot pursue him; there he lives in thought with man restored

to his natural rights and dignity . . . .

Our hope for the future condition of the human race

can be subsumed under three important heads: the abolition of inequality

among nations, the progress of equality within each nation, and the true

perfection of mankind. Will all

nations one day attain that state of civilization which the most

enlightened, the freest, and the least burdened by prejudices, such as the

French and the Anglo-Americans, have attained already?

Will the vast gulf that separates these peoples from the slavery of

nations under the rule of monarchs, from the barbarism of African tribes,

from the ignorance of savages, little by little disappear?

Is there on the face of the earth a nation whose

inhabitants have been debarred by nature herself from the enjoyment of

freedom and the exercise of reason?

Are those differences which have hitherto been seen

in every civilized country in respect of the enlightenment, the resources,

and the wealth enjoyed by the different classes into which it is divided, is

that inequality between men which was aggravated or perhaps produced by the

earliest progress of society, are these part of civilization itself, or are

they due to the present imperfections of the social art? Will they

necessarily decrease and ultimately make way for a real equality, the final

end of the social art, in which even the effects of the natural differences

between men will be mitigated and the only kind of inequality to persist

will be that which is in the interests of all and which favours the progress

of civilization, of education, and of industry, without entailing either

poverty, humiliation, or dependence? In other words, will men approach a

condition in which everyone will have the knowledge necessary to conduct

himself in the ordinary affairs of life, according to the light of his own

reason, to preserve his mind free from prejudice, to understand his rights

and to exercise them in accordance with his conscience and his creed; in

which everyone will become able, through the development of his faculties,

to find the means of providing for his needs; and in which at last misery

and folly will be the exception, and no longer the habitual lot of a section

of society?

Is the human race to better itself, either by

discoveries in the sciences and the arts, and so in the means to individual

welfare and general prosperity; or by progress in the principles of conduct

or practical morality; or by a true perfection of the intellectual, moral,

or physical faculties of man, an improvement which may result from a

perfection either of the instruments used to heighten the intensity of these

faculties and to direct their use or of the natural constitution of man?

In answering these three questions we shall find in

the experience of the past, in the observation of the progress that the

sciences and civilization have already made, in the analysis of the progress

of the human mind and of the development of its faculties, the strongest

reason for believing that nature has set no limit to the realization of our

hopes .

If we glance at the state of the world today we see

first of all that in Europe the principles of the French constitution are

already those of all enlightened men. We see them too widely propagated, too

seriously professed, for priests and despots to prevent their gradual

penetration even into the hovels of the slaves; there they will soon awaken

in these slaves the remnants of their common sense and inspire them with

that smouldering indignation which not even constant humiliation and fear

can smother in the soul of the oppressed. . . .

Can we doubt that either common sense or the

senseless discords of European nations will add to the effects of the slow

but inexorable progress of their colonies, and will soon bring about the

independence of the New World.? And then will not the European population in

these colonies. spreading rapidly over that enormous land, either civilize

or peacefully remove the savage nations who still inhabit vast tracts of its

land ? . . .

These vast lands are inhabited partly by large

tribes who need only assistance from us to become civilized, who wait only

to find brothers amongst the European nations to become their friends and

pupils; partly by races oppressed by sacred despots or dull-witted

conquerors, and who for so many centuries have cried out to be liberated . .

.

The time will therefore come when the sun will shine

only on free men who know no other master but their reason ; when tyrants

and slaves, priests and their stupid or hypocritical instruments will exist

only in works of history and on the stage . . .

economist, publicist, and philosopher, who represented the

Enlghtenment at its most optimistic.

economist, publicist, and philosopher, who represented the

Enlghtenment at its most optimistic.